A Deep South Cold Case Goes Frigid

A new law instructed the FBI to investigate more than 100 unsolved murders from the civil rights era. But the government has done shockingly little in the search for justice.

In Mississippi, tracking down the truth about a 1964 murder.

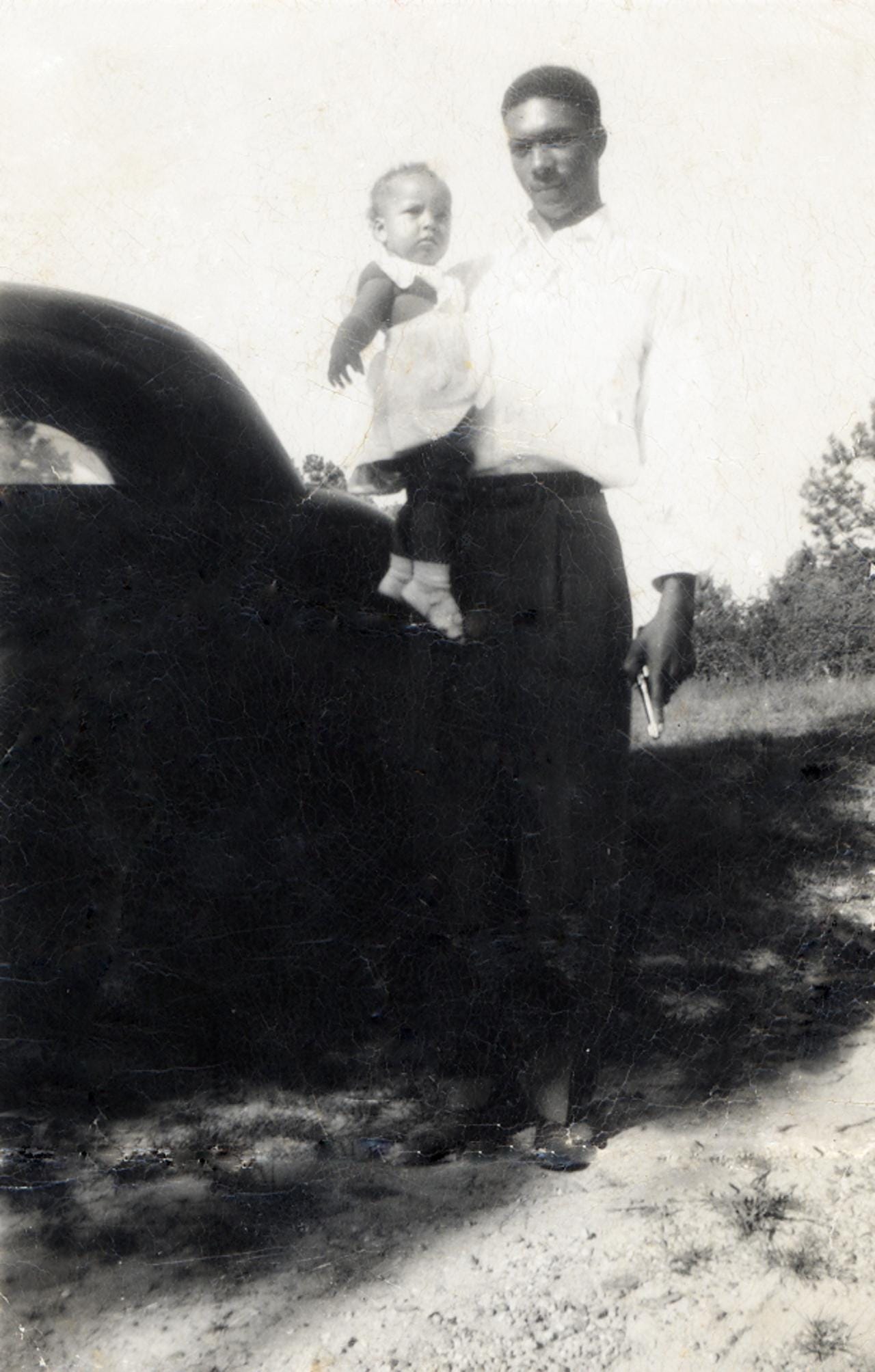

Near midnight on February 28, 1964, Clifton Earl Walker Sr., a thirty-seven-year-old black man, was ambushed by a white mob near the town of Woodville, Mississippi. He was driving home from the late shift at the International Paper plant, about thirty miles north in Natchez.

An impoverished lumber town somewhat eclipsed by Natchez’s industrial plants, strip malls and tourist economy, Woodville is best known as the birthplace of jazz legend Lester Young and home of the Woodville Republican, the oldest continuously running newspaper in the state. On the drive home, Walker took a shortcut he’d been warned to avoid off Highway 61 and onto the twisty, unpaved Poor House Road. Three hundred yards later, the attackers stopped his car, most likely by roadblock or ruse, and gathered around with shotguns.

They fired into his car at a close range. The shots blew Walker’s face apart. The next day, his body was found bled out in the car. All of the windows were shot out, multiple bullet holes were observed in at least one door, and part of the steering wheel was blasted off.

The Walker case is just one among thousands of violent, racially motivated acts from the civil rights era that remain unsolved. This one in particular illustrates the frustrations and lack of progress made since Congress directed the FBI to retroactively solve dozens of the most violent murders from this tumultuous chapter in American history.

The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007, a groundbreaking bill sponsored by civil rights hero and Congressman John Lewis, directed the FBI to conduct a “timely and thorough” investigation of Walker’s murder and 109 other unsolved civil rights cold cases. But over the last six years, the FBI has quietly informed the vast majority of the families of these murder victims that they have come up cold. Four years after re-opening the Walker murder in 2009, the Department of Justice ended its search with little to show for its efforts — and shelving dozens of other cases once again.

“All individuals even remotely implicated in your father’s death are deceased,” the Department of Justice wrote to the victim’s daughter, Catherine Walker Jones. “There are no known surviving eyewitnesses and there is no available physical evidence to review. As such, there is no reasonable possibility that further investigation will lead to a prosecutable case.”

The letter was hand-delivered by an FBI agent to Catherine Walker Jones — who was fourteen years old at the time of her father’s murder — at her home in New Orleans this past November, one week before Thanksgiving.

Instead of finding answers to what happened that night, Catherine and her siblings have been privy to false starts by a succession of agents on the case, slow follow-through on known investigative leads, and a murky, unsatisfying summation of the bureau’s efforts.

“All these years we've been requesting to meet with the Justice Department or the FBI agents, and we got no response, just promises,” Catherine Walker Jones said. “And they've closed the case and they dispatch [an agent] to give me a Dear John letter.”

The last person to investigate the Walker case was special agent Bradley Hentschel, at least the third agent on the case since it was reopened. Hentschel was assigned to the case in the spring of 2011, when he was twenty-five years old and had been employed as a special agent for less than a year.

For its part, the FBI contends that decades-old cold cases are among the most difficult an agent can be assigned. As the Department of Justice has noted to Congress: “Subjects die; witnesses die or can no longer be located; memories become clouded; evidence is destroyed or cannot be located; and original investigations lacked the technical and scientific advances relied upon today.”

All true, surely — but it was hard for Hentschel to even get the authorization and resources needed in order to conduct the most basic investigative activities in the field.

“I do not want to close this case,” Hentschel said during a telephone interview in 2011, “but if I can’t develop any further leads…it’s going to be a hard sell to the DOJ, to even my supervisor, that I need to be running around two, two and a half hours away from the office with the gas budget the way that it is and everything else, beating down leads on this case or on any other case where we don’t have any active information coming in.”

One lead Special Agent Hentschel never explored was connections between this case and the attempted killing by hooded whites of Richard Joe Butler, a black man from Kingston, Mississippi, who was twenty-five years old in 1964.

Two weeks after the Walker murder, on March 11, 1964, two cars filled with white men attempted to run Butler and his wife, Money, off the Pretty Creek Bridge as they drove home from a local store in Kingston, about fifteen miles north of where Walker had been murdered.

The Mississippi Highway and Safety Patrol, which was investigating the Walker murder, interviewed Butler about the incident near the bridge. Whether Butler exposed himself to further violence by talking to investigators is unclear, but he soon faced a white mob himself.

On April 5, 1964, Butler was in Kingston again. As on other Sunday mornings, he was working as a farmhand for a white couple, Louisa and Hayward Benton Drane. As he got to work in their barn, he found he was looking down the barrels of shotguns wielded by hooded men. When Butler tried to flee, he was shot four times and badly wounded.

Louisa Drane heard Butler’s cries for help from inside her house and came out to find him bleeding on the ground, his assailants nowhere to be seen. She helped Butler onto the backseat of her car so he could stay out of sight as she drove him to the hospital in Natchez. He made his initial recovery under police guard.

Decades later, Butler — now seventy-five, slim, with a salt-and-pepper mustache and gold-rimmed glasses — still wonders why he was targeted. “They said they just wanted to kill a smart nigger,” Butler recalled about that day, speaking at his home in California.

The stories of Clifton Walker and Richard Joe Butler are intertwined in a number of ways, perhaps most notably that local Klansman Ed Fuller, a suspect in the Walker killing, was also indicted for the shooting of Butler. After Butler was released from the hospital, he finished his recovery in hiding and then fled Mississippi — initially to Tennessee, then to Indiana and finally California. The case against Fuller and two other alleged perpetrators fell apart.

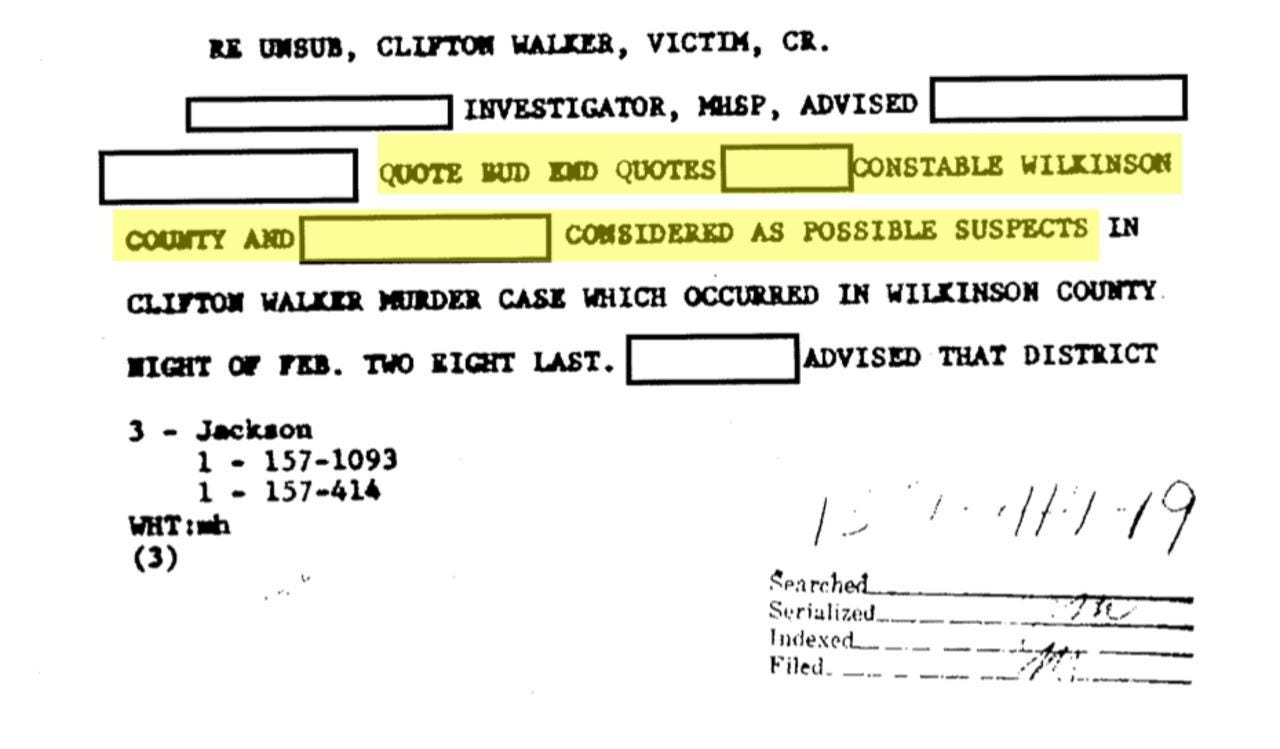

Fuller was the central link between the Walker and Butler cases, and the FBI records that Special Agent Hentschel accessed for his investigation show that Fuller became an informant for the highway patrol by November 1964. The cases are so similar and involve so many of the same people that Fuller’s informant report on the Butler shooting is included in the 1964 FBI file on the unsolved Walker killing.

In the report, Fuller asserts a different set of suspects in the Butler shooting. But highway patrol investigator Rex Armistead, for whom Fuller had turned informant, “expressed doubt,” according to the 1964 FBI report, “that Fuller was telling the complete truth,” especially because another informant claimed Fuller was personally involved in the Butler shooting.

Six suspects were originally identified and questioned by the highway patrol in the Butler shooting. At least two are still living. A third was alive when the Walker case was re-opened by the FBI in 2009, but later died in 2012. According to the Department of Justice Notice to Close File, the official internal investigative summary and legal rationale for closing a case, the FBI did not interview any of the people who had been questioned in the Butler shooting.

At least two of the Butler shooting suspects were also co-workers of Walker’s at International Paper, where racial tensions over integration of accommodations and putting an end to segregated pay lines sowed fertile ground for recruiting Klansmen. More than forty of Walker’s co-workers were believed to have joined the Klan, according to a 1965 House of Representatives investigation. Yet the Notice to Close File reveals that the FBI never sought the House committee’s list of Klansmen as part of its investigation, throwing away the opportunity to methodically interview those remaining, who could easily include valuable sources, witnesses, or even suspects.

The FBI also did not interview a single member of Walker’s family about the murder — not Catherine, who viewed the blood-soaked car shortly after her father’s body was removed from it; not her older sister Rubystein, who was their mother Ruby’s closest support and confidante through the period of the murder and its aftermath; and not Clifton Walker’s living sisters- and brothers-in-law who experienced the events following the murder firsthand.

Spokespeople for the Department of Justice, FBI Headquarters and the Jackson, Mississippi, field office, which conducted the investigation, refused to answer questions about why agents did not pursue these documents and interviews.

“We are going to decline to comment on this,” said Department of Justice’s deputy director of public affairs, Emily Pierce. “If you so wish, you can file a FOIA request.” FBI spokespersons made the same refusal and also told me to file a FOIA request.

So if the FBI ignored all these leads after reopening the case, what exactly did they pursue?

In the letter to Catherine Walker Jones, the Justice Department included thin, secondhand testimony of a possible suspect, while failing to mention much harder evidence from another source.

The hearsay testimony included in the letter came from the nephew of a man named G.B. Sproles. The nephew said that when he was eleven or twelve years old, he remembered witnessing his uncle “saw off the barrel of the shotgun before asking him why he was doing that. Sproles responded that he had something to do, and then shooed the witness away. A couple of days later the witness heard about the murder of your father and thought that Sproles was probably involved.”

The Justice Department letter to Catherine Walker Jones continued: “The witness later heard talk between the adults that your father had been killed because he was going with a white woman. He also heard that the gun used was thrown off the Mississippi river bridge in Natchez. The witness further advised that Sproles was as sorry as the day was long, but did not elaborate further on this remark. The witness indicated that he would not be surprised if Sproles was involved in the murder. As noted above, G.B. Sproles died in 1996.”

It’s unclear why this anecdote is given relevance as a finding in the Walker case. Nothing specifically ties G.B. Sproles to the Walker murder besides his nephew’s assertion that G.B. “was probably involved.” Nothing substantiates the nephew’s childhood memory as having truly occurred so close in time to the Walker murder.

By the FBI’s own account of its efforts, Sproles was the last lead the bureau pursued with any energy, but in 2010 they determined he was dead and came up with little beyond his nephew’s speculation. It’s hard to say what else the FBI did over the next three years before it closed the case in 2013, besides determine other suspects were dead and wait for important witnesses to die.

Meanwhile, another potentially more fruitful lead appears to have been ignored. An October 1964 investigative report by the Mississippi Highway Safety Patrol, obtained by the Cold Case Project at Louisiana State University, includes testimony from Barbara Jean Pike — Ed Fuller’s former girlfriend, and a possible witness and accessory to the murder who was not sought by the FBI in the present-day investigation.

During the original 1964 investigation, highway patrol investigators Rex Armistead and H.T. Richardson located and met with Pike in Anniston, Alabama, where she had recently moved. According to their report, Pike and Fuller had lived together “as man and wife” between the fall of 1963 and spring of 1964 in Ferriday, Louisiana, just across the Mississippi River from Natchez.

Pike said that during this time she knew “Ed Fuller to be a member of the KKK and that he has on numerous occasions been called on by the Klan to do various jobs.” She recalled “on one particular occasion…she drove the car for Fuller to Mississippi and watched while he got out of the car and after walking a short distance turned a headlight on a Negro and then shot the Negro in the back with a shotgun.”

Pike’s recollection that “they traveled on the highway to Woodville and then turned off to the left, traveled a short distance down a log road before stopping” sounds like a description of driving south on Highway 61 and turning left onto Poor House Road, where Walker was ambushed and shot to death.

Pike lived with Fuller during the height of his Klan activities and was privy to much that he did. She also knew members of Fuller’s family, as well as other Klansmen who were close with Fuller and were implicated in some of the same crimes as he was. While the details of her report were spotty, Pike clearly showed knowledge of significant details in a number of cases and knew Fuller well enough that the FBI should have devoted considerable energy to finding and interviewing her.

In a 2009 telephone interview with Rex Armistead, who says he was the lead investigator on the Walker case for highway patrol back in 1964, he told me Pike was important to the investigation. “She’s got all the information,” he said. “She’s got all I think anybody would need.”

Twenty-one years old in 1964, Pike could easily be alive today, but the FBI has not established if she is living or dead. “I had reason to believe three or four years ago that she was alive somewhere over on the Louisiana coast,” Armistead added. He also said that the FBI had recently tried to locate Pike themselves, but “they couldn’t find her.” If Armistead is correct about FBI attempts to find Pike, why was the effort left out of the official record of investigation? Either the FBI’s efforts didn’t amount to much, or the bureau is hiding something. To date, my own searches for Pike have also come up empty. Fuller died at forty-eight in 1975.

I interviewed Armistead at least three times, starting in 2009, but the Department of Justice investigative summary in the Notice to Close File makes no record of outreach to Armistead by the FBI at all. He died on December 24, 2013 — two months after the Justice Department closed the Clifton Walker case.

When Special Agent Hentschel first contacted me on June 16, 2011, he tried, unsuccessfully, to pressure me into giving him unpublished research that would jumpstart his investigation. During that conversation, I asked Hentschel if he was speaking to Armistead. “He’s been contacted over the course of the investigation,” Hentschel said. Either FBI contact with Armistead was not meaningful enough to report, or the bureau did not follow through on his leads and suppressed the failure in the official record of investigation.

FBI investigators also ignored another important living witness, Milton Granger, a black truck driver from Louisiana. FBI documents from the time of the initial investigation showed an interest in Granger, who had been at the Nettles Truck Stop near Woodville on February 28, 1964. Multiple Woodville residents said Granger told them he had witnessed the planning of the Walker murder at the truck stop, which is why he fled to New Orleans soon after.

Around New Years of 2009, I found a phone listing for Milton Granger’s son, Milton Jr., in Baton Rouge. Milton Jr. was eager to help Clifton Walker’s family find answers to their questions about the murder — but he would not put me in touch with Milton Sr.

Later that month, when I was in Baton Rouge on a reporting trip, Milton Jr. met me at a CC’s Coffee House. He admitted that the reason he wouldn’t put me in touch with his father was because the two are not on speaking terms. But a year later, in February 2010, when I was back in New Orleans on another reporting trip, Milton Jr. confirmed his father’s location, near the Metairie Country Club in New Orleans.

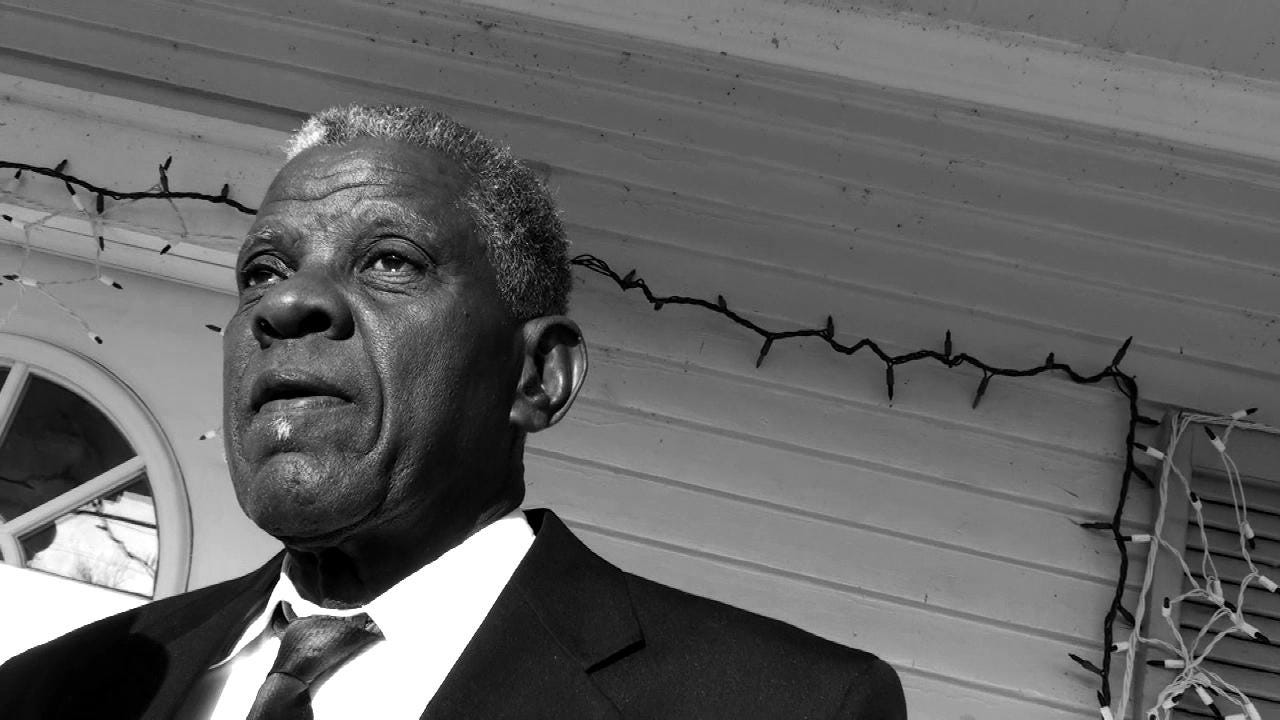

Milton Granger, Sr. was at church when I arrived at his home with Catherine Walker Jones on Sunday morning, February 7, 2010. We waited in Walker Jones’s car in front of Granger’s off-white shotgun shack, lined with cream blue shutters, bright white window frames and unlit Christmas lights strung haphazardly around the door frame.

“I knew your daddy well,” Granger told Walker Jones out on his porch, but he denied firsthand knowledge of the murder or its planning.

Granger stood dapper and animated in his black church suit and small white soul patch that matched white tufts in his close-cropped grey hair. To our surprise, Granger recalled being visited by FBI agents in New Orleans in 1964. Attempting to break his reticence, the agents showed him autopsy photos of Walker.

Granger’s memory is still sharp. He recalled specific information from the autopsy photos — photos that are not part of the surviving FBI documents from fifty years ago. His story raises questions about whether the FBI is avoiding avenues of investigation that would involve disclosing that they’ve lost documents, or would shed light on the bureau’s past mishandling of the case.

“They had him naked, laying out on the table,” Granger recalled. His memory that “the right side of his face was shot off on a slant” comports with highway patrol investigators’ descriptions of Walker’s body in 1964. Granger also remembered seeing that Walker was shot six times on his right side — twice in the shoulder, twice in the thigh and twice in the lower leg — details not captured in any of the available highway patrol or FBI documents.

By the Department of Justice’s own account, the FBI had “minimal involvement” in the Walker murder investigation in 1964. “The FBI monitored the MHP [highway patrol] … investigation and ultimately closed its case in the winter of 1964” reads the Justice Department letter to Catherine Walker Jones.

If the FBI interviewed Granger in New Orleans in 1964, however, this would be evidence that the bureau played more than a monitoring role and conducted its own investigation. This indicates there was investigative activity and evidence that is not captured in the 1964 FBI documents released to me through a Freedom of Information Act request, and not reported to Walker Jones in the Department of Justice letter.

This discrepancy suggests two possibilities: Either the investigative activity and evidence was documented in 1964, but the documents have since been lost, or the FBI has documentation of the investigative activity and evidence but is withholding it from Freedom of Information Act responses — and from Clifton Walker’s family.

FBI spokesperson Christopher M. Allen would make no comment on why Milton Granger was not contacted by agents during the present-day investigation, nor on whether the bureau lost documents from its 1964 investigation.

When I first met Catherine Walker Jones in 2008, she was working for the Federal Emergency Management Agency in New Orleans, making sure that public applicants were in compliance with regulations for receiving post-Hurricane Katrina assistance. Before the hurricane, she taught biology in New Orleans public schools for thirty-four years. In her free time she rides with the Bayou City Road Runners, a black motorcycle club founded in 1975 by her college sweetheart and second husband, Danny Jones. Walker Jones has one daughter, age forty-four, and three sons, ages thirty-two, twenty-five, and twenty-three. She and Danny got back together in 2007.

Gardening is Catherine’s other passion, outside of work, family and motorcycling. This season she is growing bell peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers, string beans, corn and okra, as well as herbs — oregano, Greek oregano, basil, rosemary — and peppers: habanero, jalapeno, sweet peppers, cayenne.

“That’s a tradition I will always keep up, because that’s what my mom did,” she said. Catherine’s mother, Ruby Phipps Walker, kept a garden behind the house they moved to in Zachary, Louisiana, near Baton Rouge, in 1965.

Before that, “She and Daddy used to raise vegetables and potatoes in the country” on the family land outside of Woodville, where they had lived, explained Catherine. They moved to Zachary because it was impossible to stay in Mississippi after the murder.

“After Daddy was killed and we were going to town, people were scared to even look in our direction,” Catherine recalled. “Do you know how that hurt me? No one stood up and cared and said what a good man my daddy was. They just turned their heads and walked, as if we didn’t exist. We became invisible. That psychologically did a lot of damage to us.

“At night after Daddy was killed, I remember the dogs barking on the hill and some old white man would come up there and turn around, and I just knew they were going to kill us. Because who was going to stop them? Can you imagine thinking like that as a kid? I knew it could happen because they had taken Daddy away.”

In 2009, Catherine, Clifton Jr. and their sister Shirley traveled back to Woodville and accompanied me to the crime scene on Poor House Road. Because Catherine saw the crime scene in 1964, she was able to help me identify the spot on the road, between high banks, where Walker’s car was stopped and the murder occurred.

“I’m not healed from that,” said Catherine. “How can you heal from growing up from fourteen to twenty-four to thirty-four to forty-four not having a daddy, not because he died from a natural cause. I wondered, how can there be a God to allow this man — that his five children and his wife depended upon for their whole existence — to be snatched prematurely?

“My baby sister—who was four years old—when she would say, ‘where’s Daddy?’ I would tell her, ‘oh Daddy is at work.’ Come on, you can’t work forever.”

Catherine started to resent her classmates. “Why should they have a daddy when mine was not there?” She also started wishing her uncles and other relatives would take revenge. “I couldn’t understand why they didn’t go pick their guns up and go retaliate.

“I made a promise to myself at that time. I would make the memory of my daddy a priority. I would make my daddy proud of everything I did in life. Even if it was not for myself, he would be my motivator. And that’s how I lived my life.”

“When that [FBI] cold case initiative came out, everyone was just so hopeful,” she remembered. “They were going to invest the time, and they were going to come up with something before all of the possible or all of the prospective witnesses actually died. But that just didn’t happen. No it didn’t.”

Part of Special Agent Hentschel’s investigation included gathering information from me about the case. I am a blogger and investigative reporter who has been covering civil rights cold cases since 2004. I’ve been investigating the Clifton Walker case since 2007.

Hentschel prodded me aggressively to give him anything I had developed that could advance the Walker case. He wanted my work pre-publication, but I couldn’t ethically provide that. “If there are other people we need to talk to who haven’t been talked to, I’m not sure how I’m going to know that other than you telling me that,” he said. The thing he wanted to know most was how to find a woman named Emma Beasley.

Walker’s nephew, Hayward Dixon, had heard allegations in 1964 that Beasley and someone known as “Cripple Armed” George, both African-American, were used by the lynch mob to get Clifton to stop his car on Poor House Road the night of the killing.

Cripple Armed George is reportedly dead, but it turned out Beasley was still alive.

I started trying to find Beasley in 2007 when I first obtained 1964 highway patrol reports on the Walker case. According to investigators, Beasley had “knowledge of certain facts that would aid greatly in breaking this case.”

A cook at the Nettles Truck Stop, where the murder was allegedly planned, Beasley “left Woodville immediately after Walker’s body was discovered,” said highway patrol investigators. She reportedly “returned to attend the funeral, and immediately after the funeral, left.”

“I know too much about this mess and I ain’t gonna get involved,” Beasley reportedly told her common-law husband, and “left in such a hurry that she took no clothes except those she was wearing.” Beasley took up residence in Amite, Louisiana, with a boyfriend she’d been seeing there off and on. Between her fear and her Mississippi partner’s existing, legal marriage to another woman, Beasley had little interest in returning to Wilkinson County.

For two years, neither Lexis Nexis, phone books or my network of local sources yielded any leads at all regarding the welfare or whereabouts of Emma Beasley.

I tried contacting Wilkinson County Sheriff Reginald Jackson. I figured that, as sheriff he would know who’s who in the county, and as the first African-American to hold the office — and as a relative of the Walkers — he was likely to help.

I called Sheriff Jackson many times — at the Wilkinson County Sheriff’s Office and on his cell phone — but never reached him and never received a call back.

“Reginald Jackson will not talk to anyone in the press,” said Andy Lewis, publisher of the local Woodville Republican newspaper. “He hides out there in his office. His secretarial staff protects him.”

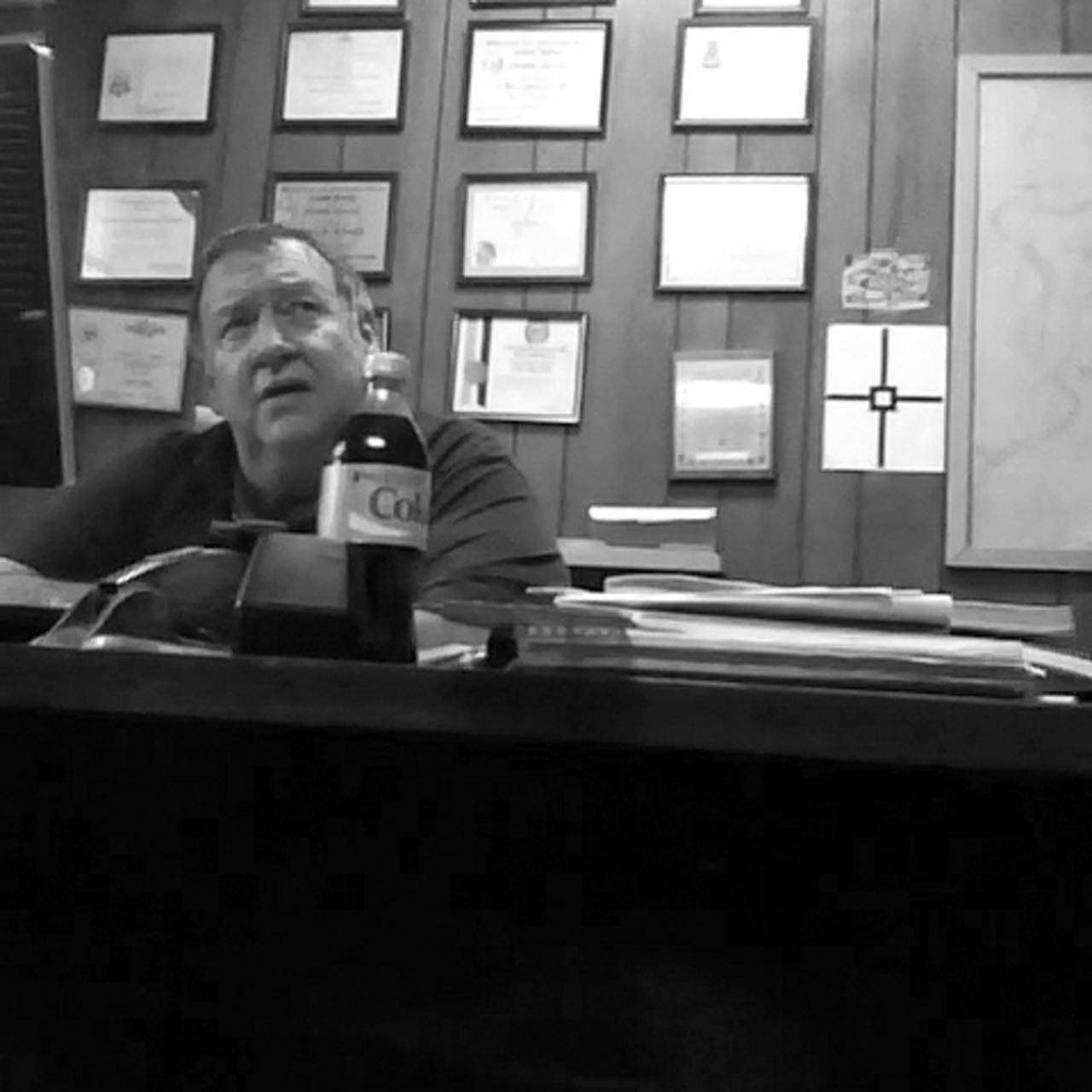

There are two towns in Wilkinson County: Woodville, the county seat, bordered by Louisiana to the south and the west, and Centerville, fifteen miles east. After a failed attempt to catch Jackson at the Sheriff’s office in 2009, I decided to try Centerville Police Chief Jimmy Ray Reese. An available white police chief was better than the black sheriff who was avoiding me.

I called the Centerville Police Station. Reese’s secretary confirmed he was in, and I drove there from Woodville.

“Chief, the reporter’s here,” yelled out the black woman in her thirties from the glassed-in control room by the entrance.

“Come on back,” came a shout from down the wood-paneled hallway.

The police chief was at his desk when I came in. Heavyset, red-faced and informal in his navy blue polo shirt, Reese fit the stereotype of a white southern lawman.

“Jimmy Ray Reese,” he said, introducing himself with a resonant drawl. “What can I do for ya?”

A blue Ethernet cable hung from the ceiling down to the floor by the far wall and ran to the computer under Reese’s desk. The wood paneling behind him was covered with plaques and certificates.

“Would you like some coffee?” Reese asked with a hearty smile, tipping his Styrofoam cup in my direction, a cigarette smoldering in the ashtray on his desk.

Reese remembered the Walker murder. He was ten at the time, the same age as Clifton Walker Jr.

As an adult, Reese heard more about the murder from his former boss, Wilkinson County Sheriff Burnell McGraw, who served from 1960 to ’64 and again from ’68 to ’92. Reese first worked for McGraw in the early ’70s.

“It was over him either using the white restrooms or drinking out of the white water fountain” at International Paper, Reese had heard.

“Back in those days they had the signs,” Reese said. “He’d been told don’t do one or the other. And apparently he did and he was found shot with buckshot. Something like 250 holes were found in his car.”

Federal authorities suspected that McGraw, who was not sheriff at the time of the murder, was a Klansman, and according to Reese, the FBI picked up McGraw to see what he might know about the killing. “He told them he didn’t know more than what the people on the street know,” said Reese.

I explained I was looking for Emma Beasley. The rumor was that she had moved back to Mississippi twenty or twenty-five years ago and opened up a club called Emma’s Place.

“Her name was Beasley?” Reese asked. “I know her. Me and Emma always got along real good. Emma Sims. Mary Emma is her name. Mary Emma Sims.”

“She still around?” I asked

.

“Yup,” he replied, “I talked to Emma last week. She was involved?”

“She’s mentioned in the documents as having knowledge,” I explained.

“I’ve been in law enforcement in this town thirty-three years, thirty-four years in January. She’s been here ever since then. She ran a big night club. I know her quite well, and we always got along good.”

“When she ran that juke, I was the deputy and we had a lot of dealings,” Reese continued. “A lot of them at these jukes don’t like to tell you who was fighting, but she’d always point ’em out to me and have ’em arrested and try to stop things. She tried to run a pretty good place. She had a lot of pull back in them days.”

“Never heard of that name, Beasley,” Reese said, picking up a phone book. “That’s gotta be her, I mean she ran a juke. It’s turned into a church,” he added, laughing.

Reading from the phonebook, “Mary Sims,” Reese said again. “I ain’t gonna tell her you’re comin’, she might get worried. Just gonna ask her.”

As he dialed the phone, Reese yelled, “Derrick! Bring the coffee pot!”

A black teenager, seventeen or eighteen years old, came in with a full pot of coffee.

“Emma. This is Jimmy,” Reese said into the phone while holding out his cup for Derrick to pour.

“Emma, what was your maiden name?…Thompson? You ever heard of a Beasley?…That was your first husband’s name?…And then you married Robert Sims…Alright, somebody just said Mary used to be a Beasley, and I was wonderin’ about that.

“Alright then. I ain’t tryin’ to scare you. You ain’t never done nothin’. Alright, alright Emma.”

“Me and her are good friends. We really are,” Reese said, hanging up the phone. “I knew she had come from up there in Buffalo, which is about five miles north of where that road is you talked about, the Poor House Road.”

Emma’s place was just a couple of miles south of the police station, on Highway 33. “You’ll pass a John Deere tractor place,” Reese said, offering directions. “Then maybe a half-mile there be a nice brick home on the left, a little pond beside it.”

Reese’s cell phone rang. “Alright, feed your horse, and I’ll be there,” he said to the caller and hung up.

“After you pass that nice brick home,” he continued, “it be a cattle company on the right, where they haul a lot of cattle in. Straight across the road there, on the left, just past that brick house, will be a big white building and there’s a house straight up beside that big white building, a house trailer. Emma lives in that trailer.”

“You can call me anytime the day or night, and no time ever disturbs me,” Reese added. “If you need anything, just holler, and I’ll help you any way I can.”

I met Emma the next morning. She was eighty-one and tall, even as she bent to use her cane. She had small, braided pigtails pinned tightly behind her ears. She was getting over the flu and was wearing a white terrycloth robe. Her recollections closely tracked details in the 1964 highway patrol documents.

“They come down there and they questioned me,” she said. “They knocked on the door, I answered the door and they just pushed the door on over.”

Emma appeared still traumatized from her interview with the highway patrol’s Rex Armistead, who had discovered her in Louisiana, where she’d fled after the murder. During the interview in 1964, Armistead showed her crime scene photographs of Walker’s mutilated head.

“It was just his face and it was horrible. Horrible to look at,” she said. “That stayed on my mind a long, long time.”

The first time I interviewed Beasley, Emma firmly denied knowing Clifton Walker at all. This was despite the recollection of Hayward Dixon, Walker’s nephew, that Emma regularly visited the juke joint that his mother ran on the Walker family land. Hayward is adamant that Emma frequently hung out there with Clifton Walker and others.

Emma said she didn’t remember any of the people who stopped in at Nettles Truck Stop, where she worked — not Walker, not any of the members of his carpool, not the alleged conspirators who were seen there the night of the murder. She didn’t work at night, she explained. “I would cook dinner and then I would get off.”

But then Emma contradicted herself, saying, “All I remember is that he worked at the mill, in that line,” and then quickly added, nervously: “I didn’t know he worked at the mill until after this happened.”

In February 2010, I returned to interview Emma again, this time with Catherine Walker Jones accompanying me. On that occasion, Emma volunteered further, “I been to their house one time. One time.”

Emma said nothing about the murder itself, but she appeared deeply fearful.

A year after he first called me, Hentschel still had not contacted Emma Beasley, in July 2012. Reached on the phone, she told me she had gone blind from diabetes and her health was failing. She’d been hospitalized multiple times in recent months and was receiving regular home visits from nurses.

According to the Department of Justice letter to Catherine Walker Jones, the FBI finally located Emma Beasley on February 14, 2013. The letter carefully uses the word “located” rather than “contacted.”

Deborah Madden, spokesperson for the FBI’s Jackson, Mississippi field office, would not confirm or deny that Hentschel or any other FBI agent spoke to Emma Beasley.

The information reported in the Department of Justice letter to Catherine Walker Jones precisely reiterates Beasley’s claims to the highway patrol in 1964. Nothing reported reflects a present-day interaction — no new information about the case and no other information about Beasley.

Nor does the letter mention that Beasley died on June 25, 2013 — information that would surely be relevant to Catherine Walker Jones, who sat across from Beasley as she offered evasive denials in 2010.

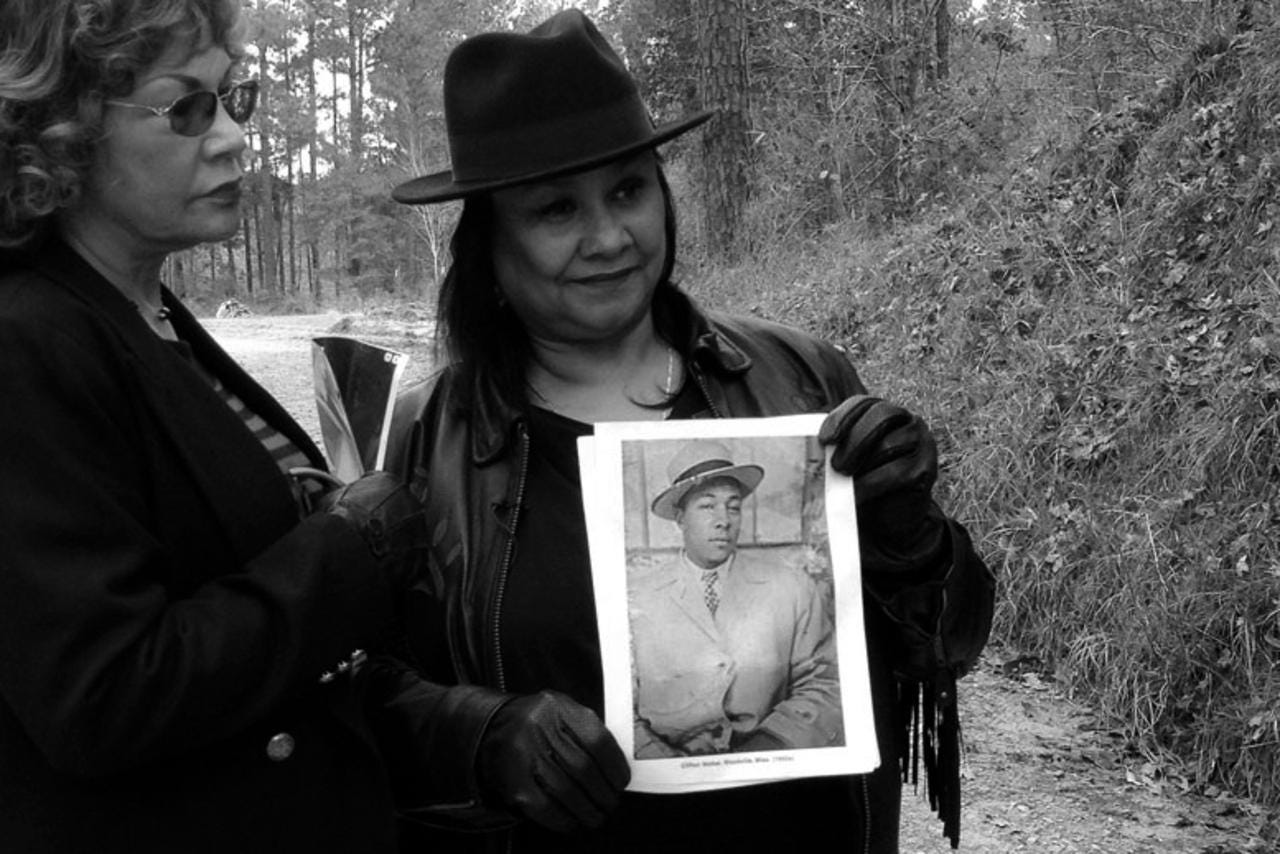

In December 2013, we returned to Poor House Road. Al Jazeera English wanted to cover the closing of the Clifton Walker case and brought Catherine, Shirley and myself to Mississippi for on-location interviews. It was the sisters’ first time back at the crime scene since 2009. They were eager to speak on their father’s behalf and give voice to their disappointment with the Justice Department’s decision to close his case.

When we met up in Woodville, the Walker sisters seemed worn down and more subdued than in the other meetings we’d had over the six years I’ve known them. The family had been through a lot in the previous year. On November 1, 2012, Clifton Jr.’s son, Clifton Walker III, was murdered at age twenty-seven in an apparent robbery in Baker, Louisiana. His body was found in the trunk of his own vehicle. An arrest was made, and the case is still unfolding in court.

“It took him [Clifton Jr.] back in the moment when Daddy died,” Catherine said. “That was something we had to endure with Cliff.”

Then in June 2013, a small eight-passenger plane went out of control and crashed into Cliff Jr.’s home in Baker, Louisiana. “The wing clipped his house and spilled jet fuel onto his house,” explained Catherine. “He had to move out.”

And then the FBI agent arrived at Catherine’s home in New Orleans to deliver the dispiriting news. “To get that letter in November, on my mother’s birthday, November 21, 2013, to get that letter saying they closed the case, that was really a blow,” Catherine said. “They only reported what was already done. There was nothing new.”

Catherine stood on the unpaved gravel and earth between the high, tree-lined banks where, fifty years earlier, their father was found brutally murdered inside his car. She wore a black fringe leather jacket, red stencil cut flower on the lapel and a homburg hat similar to those her father wore. Shirley stood close by.

“We lost our father here. Our mother lost her husband here,” Catherine said, looking into the camera. “This place where Daddy was murdered has held all the secrets. Daddy, we are still seeking the truth. We want the world to know we will never stop.”

While the sisters held a photo of their father for the camera, Catherine felt her legs going numb. They gave out from under her. Shirley and I caught her.

“I suffer from sciatic back pain. And a lot of stress aggravates the back,” Catherine later explained. “That’s frightening too, to realize you don’t feel your legs. I haven’t had an episode since then, matter of fact.”

In the letter to Catherine Walker Jones, the Department of Justice asserted that the FBI played a minimal role in the 1964 investigation and that highway patrol led “a disjointed investigation that failed to produce enough evidence to charge anyone in the murder.”

Yet the letter also shows that the 2009 to 2013 investigation was based almost entirely on retracing the steps of the 1964 investigation — the very investigation that the Justice Department themselves criticized. If the individuals implicated and the eyewitnesses identified in 1964 did not yield sufficient evidence for prosecution, it stands to reason that a rehash of the 1964 investigation would not lead to a prosecutable case.

Even when the FBI pursued remaining living subjects, the agents made only minimal contact. Eliciting information from a resistant source requires rapport building over time.

In other cold cases, the FBI seems to have essentially ignored sources who came forward with new information. Stanley Nelson, editor of the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday, Louisiana, has reported extensively on two civil rights-era cold cases that were reopened under the Till Bill and closed in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

“I had individuals tell me that they contacted the FBI to tell what they knew about these cold cases, but that the bureau showed little or no interest in what they had to offer,” Nelson said. “In some cases, the caller was asked if he or she could provide ‘probative’ information — did they have evidence as to who killed who? That’s a ridiculous approach. You have to look for ‘pieces’ of the story rather than the one caller or witness who has all the answers.”

Nelson came to realize that the FBI agents could only do as much as their superiors in the Justice Department directed them to do. “Had a handful of agents working in the field been given the time and tools to do nothing but work on these cases, then they would have accomplished much more,” he said.

Rep. John Lewis, who authored the Till Bill, wishes more would be done to bring justice and peace to the victims. “The history of law enforcement in this country suggests that issues of transparency and the open admission of fault when errors have been made are a long-standing challenge,” said Lewis’s spokesperson, Brenda Jones. “The Congressman cannot presume to know what has stopped more thorough investigation, but demanding an answer to that question from the agency itself may help lead to more satisfactory progress.”

“One bill will not bring a resolution to the deep-seated issues that have made these injustices possible and outstanding for decades,” Jones emphasized. “It is important for people inside and outside the government who are passionate about this issue to continue to push and pull, raise their voices, ask questions and demand answers.”

The handful of civil rights cold cases successfully prosecuted before the Till Bill were largely a matter of piecing together cases that were already there, based on investigations and court cases from the 1960s. Existing investigative documents and trial transcripts were roadmaps for establishing the cases against suspects in the more recent years.

But in the Walker case, the existing investigative work from 1964 is inconclusive. The investigative documents are rich with information that could be the basis of a fuller, more complete investigation. But that investigation was simply not undertaken.

Some portions of the article are based on earlier blog posts published on Ben Greenberg's blog, hungryblues.net.

Ben Greenberg is an investigative reporter and photographer based in Boston. He is a founding member of the Civil Rights Cold Case Project. His work has appeared in NPR Code Switch, USA Today, Colorlines, The American Prospect, The Clarion Ledger and elsewhere. Greenberg can be reached at minorjive@gmail.com.

Clarence Smith Jr. is a writer and visual storyteller living in New England. He is also the founder and editor-in-chief of BOLD Edition, a "portfolio as publication" that explores The Bold motif through original journalistic storytelling.