Confessions of a Cam Girl in an Age of Loneliness

Every night I sit in my room and live-stream my boring life. I don’t take my clothes off. I don’t dance. Yet people show up and pay me anyway.

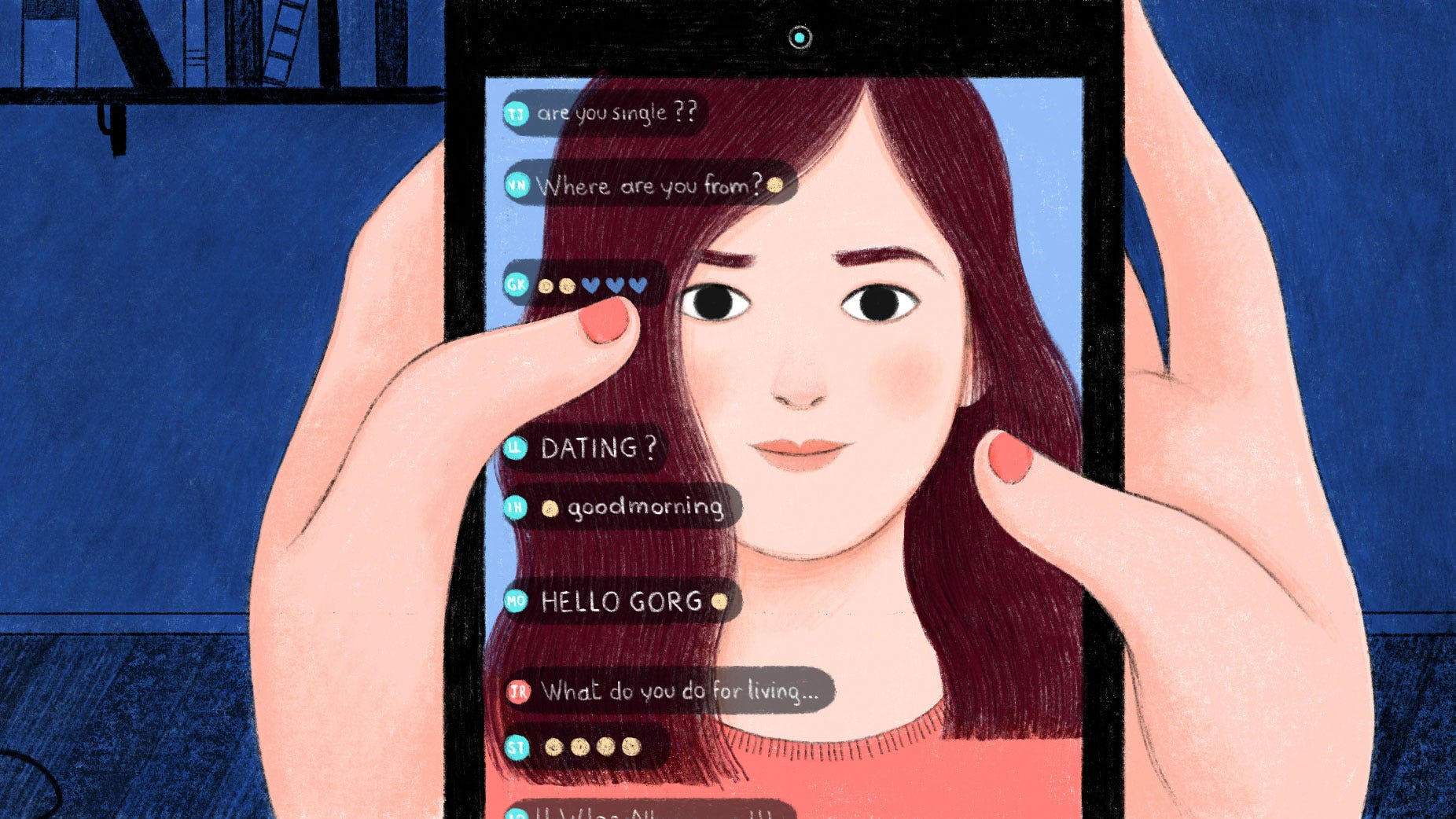

Illustrations by Giulia Tomai

At 7 o’clock in the evening, seven days a week, I can be found sitting on one end of my bed in Manhattan, posed in front of my phone as I address hundreds of strangers. “Hi, you guys,” I say — because the majority of my viewers are men — followed by my usual nightly greeting: “It’s been such a long day.” I pout slightly, my eyes trained on the camera to give the illusion I’m speaking directly to each individual viewer.

I watch as more sign in and the count rises — 300, 400, 500. Comments start popping up from the bottom left-hand side of my screen: innocent greetings like “good evening” and flirtatious ones like “hello gorgeous” mixing and melding, quickly pushed out of view by those that materialize below them. Soon, they start to appear so rapidly that I can’t keep up with every comment.

They ask me questions: “What did you do today?” “What part of New York do you live in — the city or upstate?” “What do you do for a living?” They ask me more personal ones…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.