Daisy Jambawo’s Sad, Strange Trip

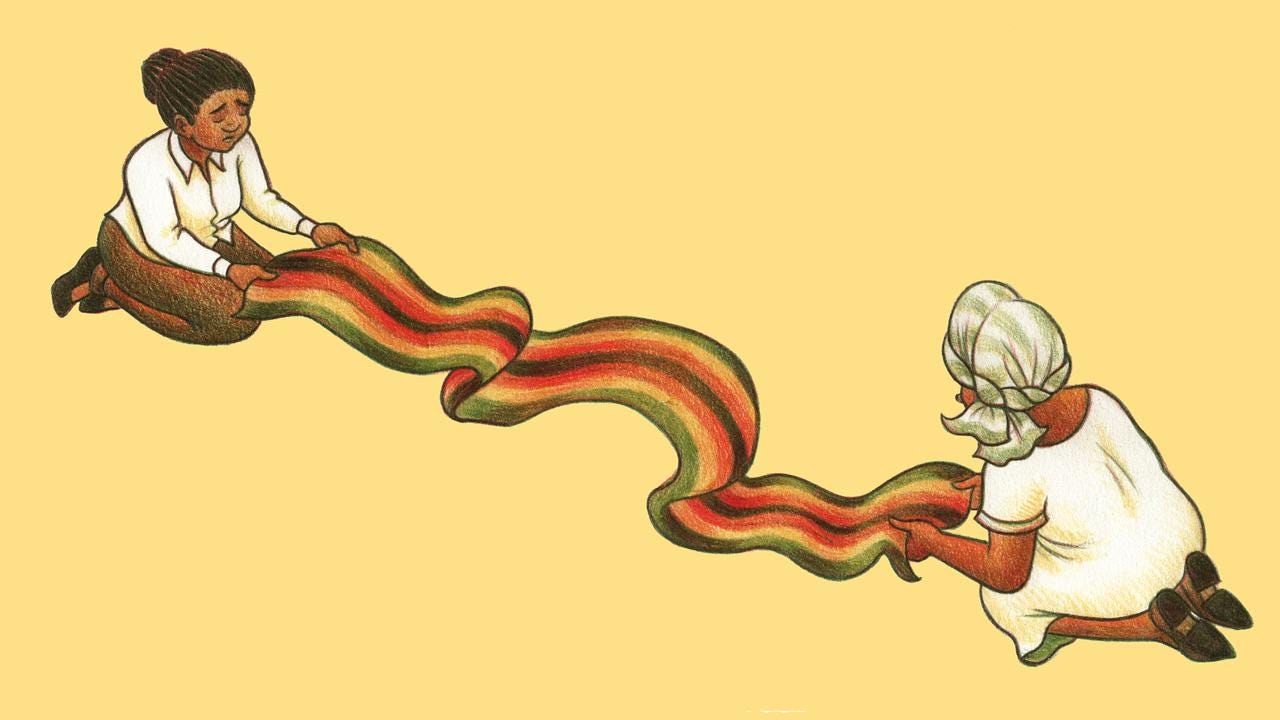

When a Zimbabwean immigrant is murdered by her husband, two families across two continents erupt in a months-long struggle to bring her body home.

On the morning of December 5, 2012, Winlaw Muzirwa, a thirty-eight-year-old former prison guard, walked into the Tinicum Township, Pa., police station in blood-stained clothes, asking to be handcuffed for shooting Daisy Jambawo, his wife of fourteen years, to death.

The police found the thirty-four-year-old woman’s body on the bedroom floor of the couple’s apartment on Third Street. She had been shot twice, in the face and back, with a Ruger P95 pistol while her fifteen-year-old stepdaughter, fourteen-year-old daughter and eight-year-old son were at school.

Aside from her husband and children, Jambawo didn’t have any direct relatives in the United States. Her two brothers were in Zimbabwe and her cousins were in the U.K. Informed of the tragedy, her extended family was immediately preoccupied with one thing, aside from taking care of the victim’s children: They had to organize the transport of the woman’s remains from the United States, where she had live…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.