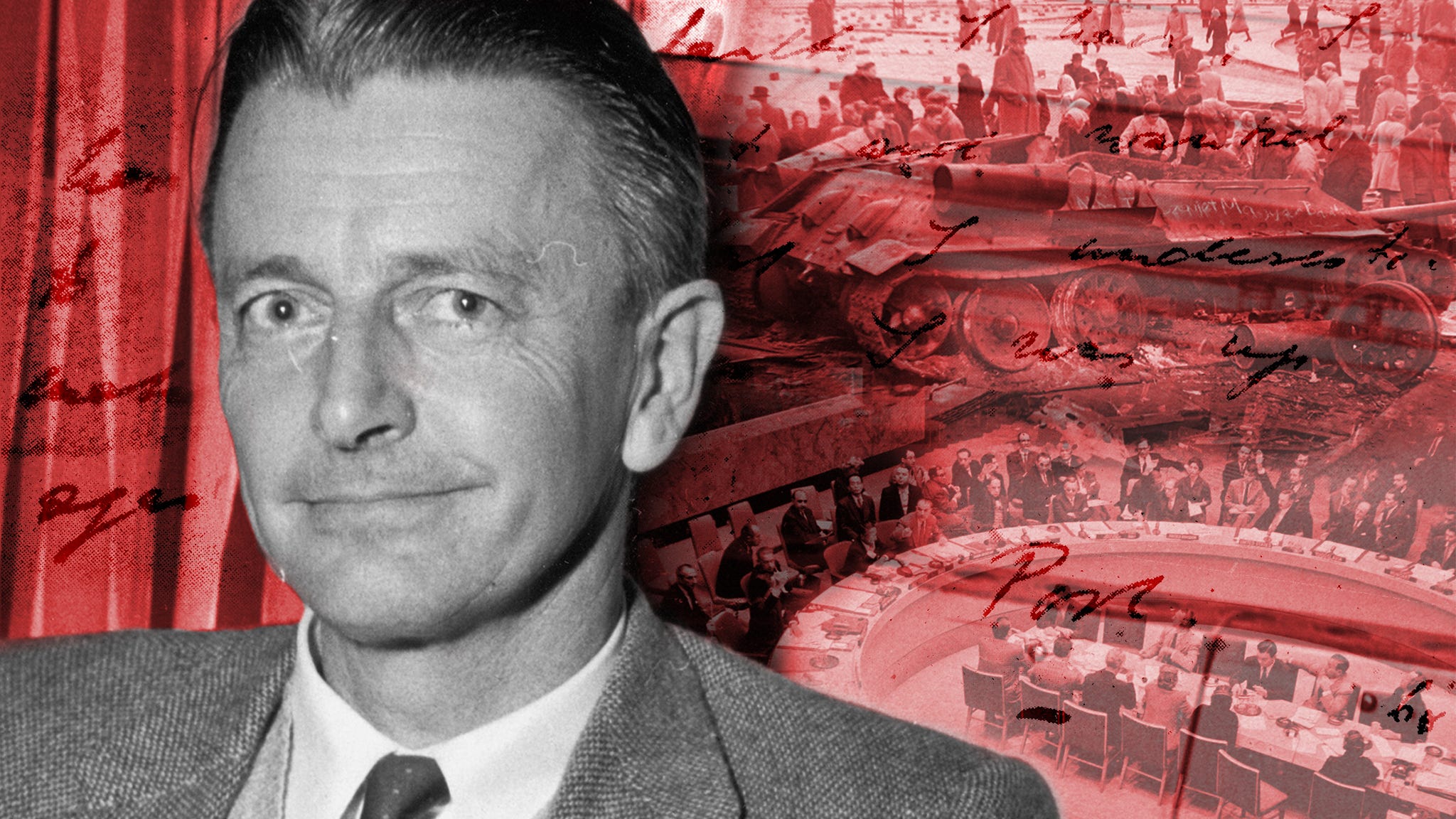

The Daring Diplomat Who Proved One Person Can Thwart an Empire

A whistleblower puts his life on the line to defy Soviet aggression. Sixty years later, this forgotten story of subterfuge, smears and suspicious death has never felt more timely.

Collage by Yunuen Bonaparte

On October 23, 1956, waves of demonstrations rolled through the streets of the Hungarian capital. The citizens of Budapest converged on government buildings, protesting the influence of the Soviet Union on their elected officials and economy, and the presence of Soviet troops in their cities. What began with a few thousand university students swelled to include workers, soldiers, and men and women of all ages. Someone pulled down a Hungarian flag, emblazoned with the Communist sickle and hammer. They tore out the insignia, leaving a gaping hole in the middle. It became a symbol of the revolution.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.