Drinking with the Dead

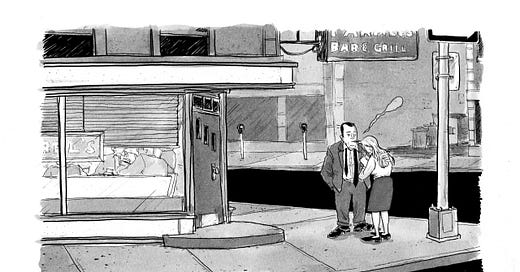

In a rollicking pub on the edge of the Bronx, an Irish-American enclave clings tight to the tradition of celebrating, rather than mourning, their dead.

As they talk passionately in chairs rearranged around the funeral home, my family members aren’t happy, but they aren’t sad either. They talk about how the dead loved the Yankees, or going to Cape Cod. They talk about anything except the body at the front of the room.

I remember scenes like this from my childhood, when Irish relatives close or distant passed away. I remember the happy parts of deaths: the storytelling, the laughter, the tears, and the smell of tobacco and old beer. The tears weren't only due to sadness. The salty discharge was more about the void left by the person: the void of no more conversations, no more hugs, handshakes, or kisses. You cried when you realized you couldn't pick up the phone to hear them, when you couldn't ask them for advice, when you couldn't see them smile. The funeral was immediately followed by a reception at a bar or a bar & restaurant (a fine, but important distinction). There were also…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.