From the Bowels of a Beast

In the foggy hills of the northern Philippines, committed and courageous harvesters reach into the unlikeliest of places to produce some of the world’s most coveted coffee.

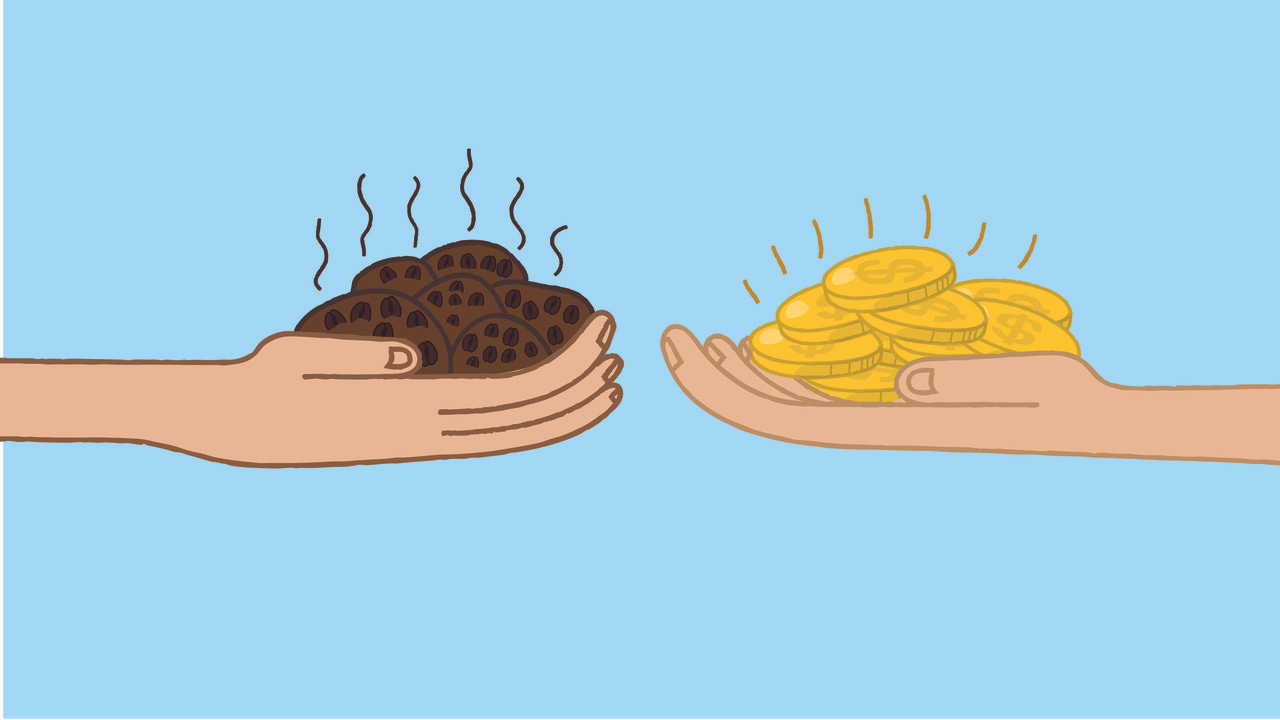

Civets—furry, weasel-like creatures with pointy noses and a love of frolicking over rocks and up and down trees—have long been valued for their excretions. African civets were the original source of perfume musk, scraped from the skin of living civets or squeezed from the glands of dead ones. In India today, as in ages past, the oil extracted from pieces of their meat is still used as an indigenous cure for scabies. In Southeast Asia, civets shit gold.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.