Getting With the Pajama Program

What a pair of jammies can mean for NYC's processed youth.

At a homeless shelter up in Harlem, a little girl watches as a woman hands out pajamas to other children. When a pair is handed to her, she doesn’t take them. Instead, she asks, “What is it?” She had never owned a pair of PJs in her life.

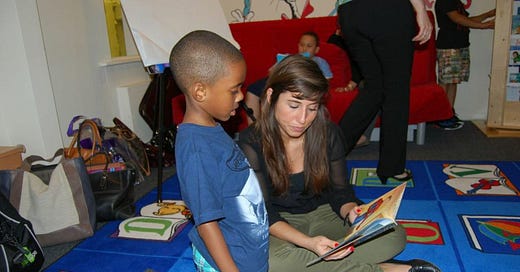

It can be hard for most of us to imagine a childhood like this, one handled by the Administration for Children’s Services. “Some of these kids have never gotten anything new, anything that’s clean or that fits them,” explains Genevieve Pitturo, founder of the Pajama Program, a nonprofit that brings books and pajamas to children in need. “They’re brought into these places with nothing but the clothes on their back, which are often dirty, or hand-me-downs that don’t fit.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.