Grooving to the Oldies at New Orleans’ Temple of Uncool

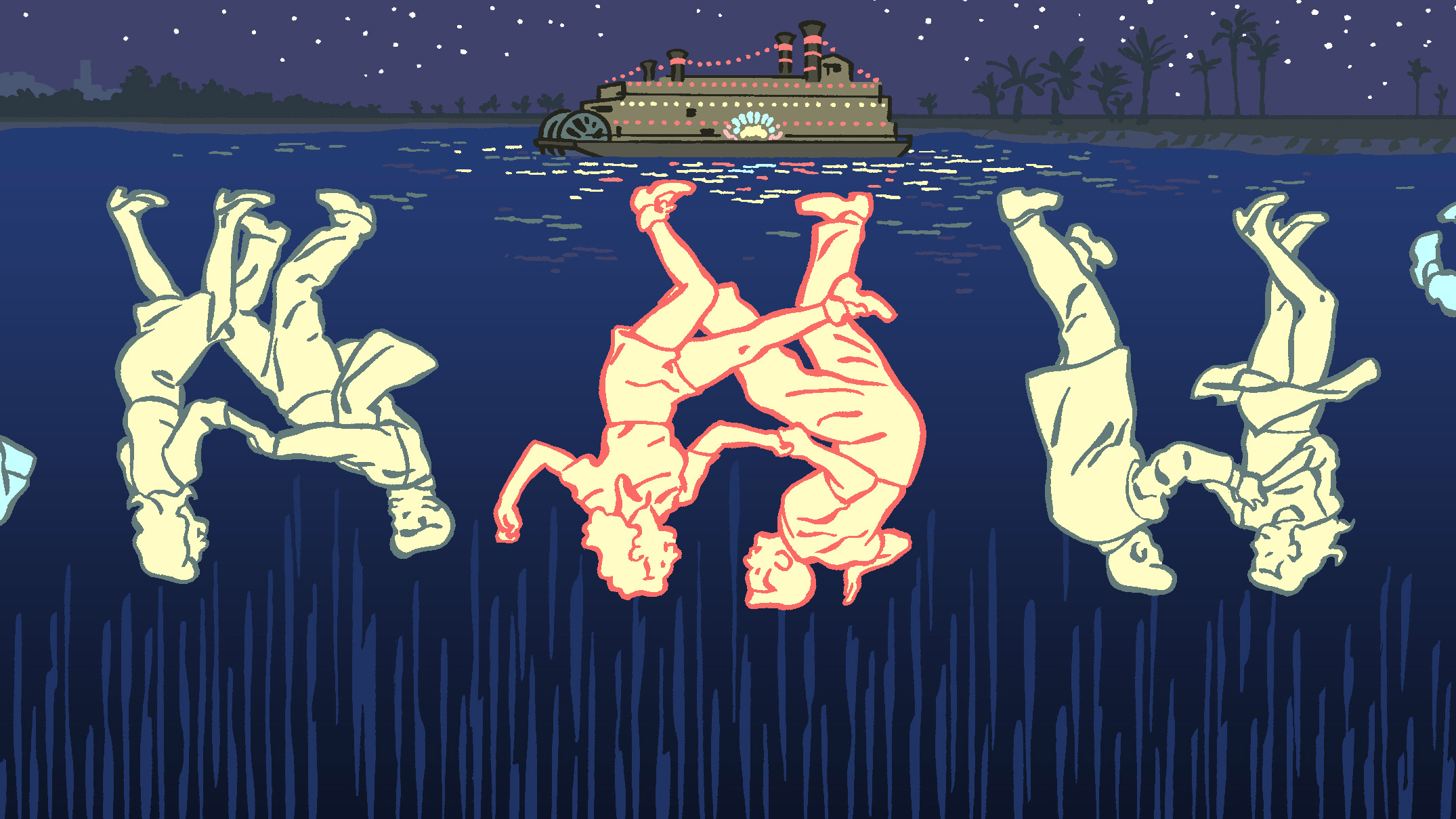

Tourists love the legendary jazz clubs. But if you really want to know NOLA, step back in time aboard a retro riverboat casino docked just off an interstate near the airport.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.