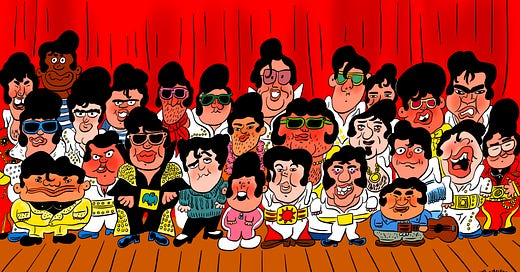

How 26 Elvises Taught Me to ‘Follow That Dream’

Just when I was ready to call it quits, a flock of tribute artists dressed as The King inspired me to give it my all, no matter what.

Illustration by George Mager

The sound of slot machines rang out and cigarette smoke lingered in the air. I hummed along with A-Ha’s “Take On Me.” It was the usual buzz of the casino, although here off the strip, at Sam’s Town Hotel and Gambling Hall, there were fewer swanky dresses and more RVers in sloppy t-shirts parked with their ashtrays and bourbons at the slots. But I didn’t come here for the casino. I came here to see Elvis. All 26 of them.

When my sister Ila announced that her husband, Clint, was performing in an Elvis impersonator contest, I was all in. I didn’t understand the appeal of Elvis impersonators, or tribute artists as they prefer to be called, but I was curious. Besides, I needed a vacation. The past year I’d been furiously submitting essays for publication and the rejections were stacking up. I’d been more disciplined than ever with my writing, but I was exhausted and rejection weary. Cocktails in Vegas with The King sounded like the perfect escape.

The Elvis compet…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.