How Kenny Washington Broke the NFL's Color Barrier...And Why You've Never Heard of Him

He pushed past brutal racism to become the first Black player in major league sports—a year before Jackie Robinson—yet even his own kids never knew his full story. It’s time everyone did.

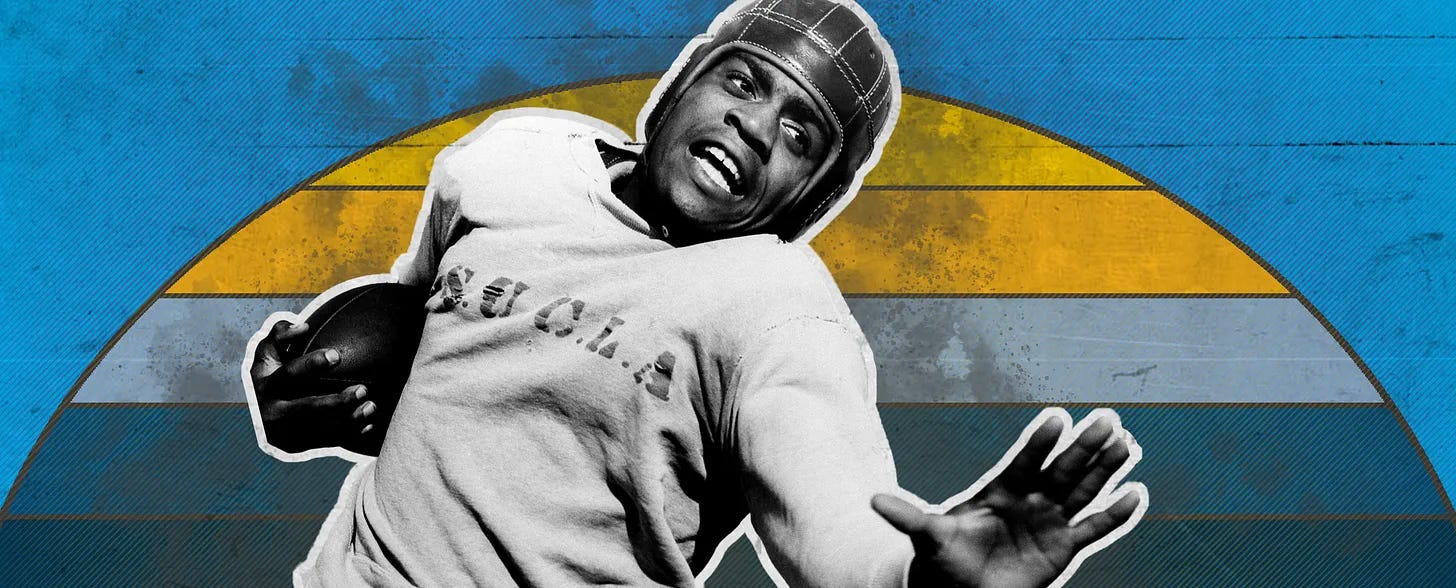

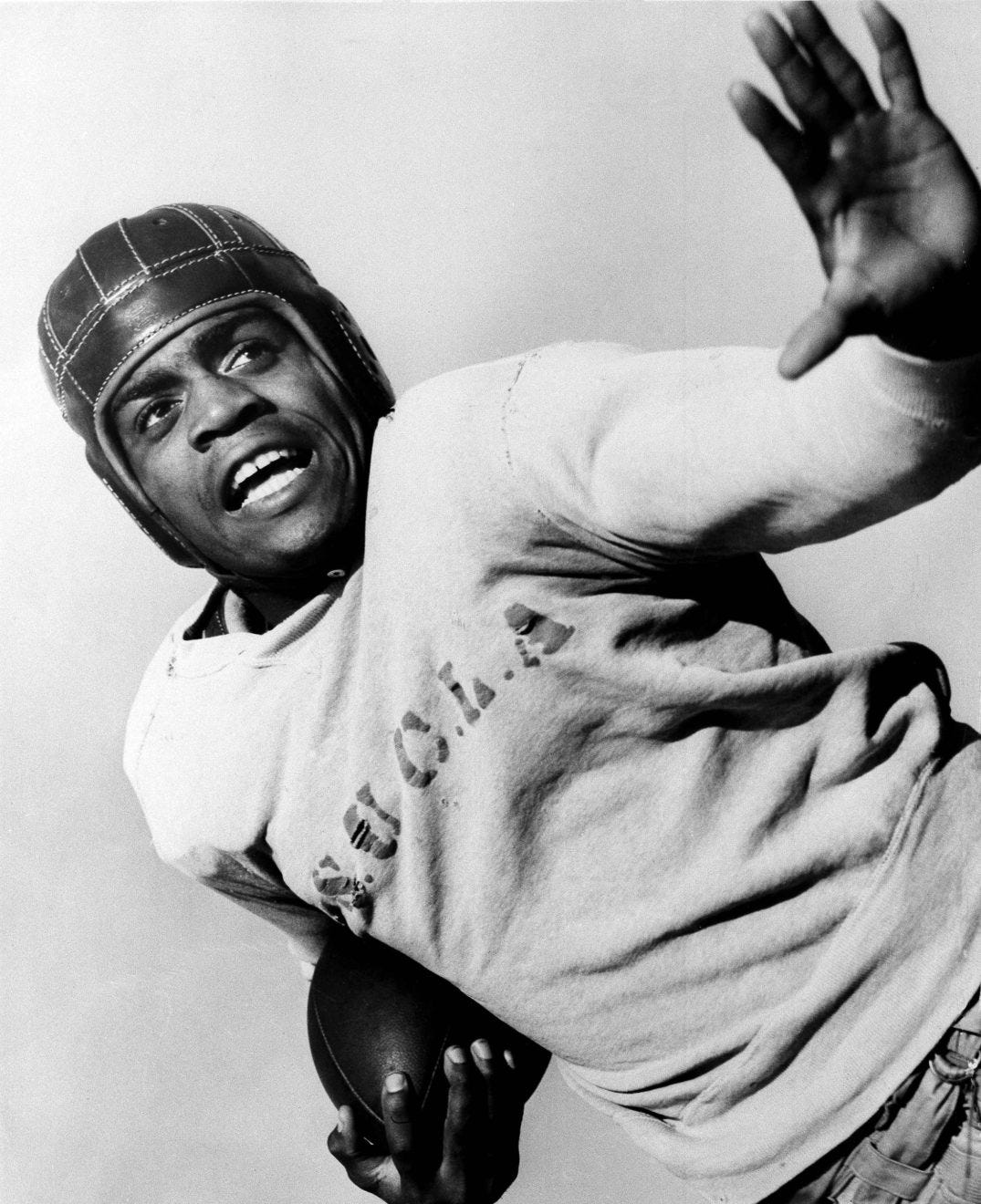

Awaiting the snap, Kenny Washington scanned the Philadelphia Eagles defense, who were digging their cleats like enraged bulls. All of the white men scowled, making it impossible to know which of them might try to inflict a punishment more severe than tackling him. It was 1946, a year before Jackie Robinson would take the field in Brooklyn, and Kenny Washington had just broken the NFL’s color barrier. Los Angeles Rams coach Adam Walsh seemed to waver about playing Washington; he didn’t insert the former University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) star until late in the fourth quarter, down 23-14 to the Eagles. Playing quarterback and backed up against his team’s end zone, Washington faced long odds. With time running out, everyone in the L.A. Coliseum, including the Eagles defense, could predict the play, knowing that Washington would have to rely on the cannon arm he’d used to mount epic comebacks for UCLA, often in this same stadium. But that was seven years ago, a lifetime in football years. Washington breathed deep and listened to the cheers of the crowd, including loyal Black fans who had followed him since high school. Adrenaline almost numbed his aching knees, which had endured a fifth surgery to make this season possible. With lips pursed, the grin that he had become famous for remained hidden under his trim mustache. Washington’s maskless leather helmet, soaked with sweat from the 95-degree day and dampness from an earlier downpour, would offer little protection. Washington received the ball, cradling it less than a second before finding the laces and cocking his arm. As defenders closed in, Washington fired to a receiver downfield. The pass missed. He missed on another try. And another. Washington completed just one of eight passes in that game. On one desperate play, he avoided a hit by running out of his end zone for a safety. He staggered off the field after the loss, wondering how it had come to this. After all the work. All the pain. He’d be damned if this was how people remembered Kenny Washington.

In 1939, Kenny Washington was the college football star, leading the NCAA in total yardage and winning the Douglas Fairbanks Trophy as most outstanding player. Still, NFL teams refused him. And although he eventually became the first Black player to go pro in any of America’s big four sports post–World War II, he’s the only player among those who broke the color barrier in these major league sports who has not been inducted into his sport’s Hall of Fame. A shameful era of football still hides in a whitewashed history inflated with more than its share of Lambeau and Lombardi legends, rendering an early civil rights hero a real-life Invisible Man.

“In many ways sports set the tone for America to begin integration,” writes Charles K. Ross in Outside the Lines. “The NFL was the first major sport to lower its color barrier during the postwar period, though not without a struggle.” Washington died at 52 years old in 1971, long before seeing his sacrifice lead to an NFL that’s now nearly 70 percent Black players. His daughter, Karin Washington Cohen, says full credit for his part in the struggle is overdue. Washington Cohen’s parents divorced when she was 8 years old, and although her father still lived nearby and moved back into their house when his health began failing, Washington died when his daughter was 15. He didn’t brag about his glory years, so Washington Cohen has mostly learned about her father’s football career from the documentary filmmakers and writers who have tried to uncover his buried legacy in the last couple of decades. Washington Cohen knows many of today’s young players couldn’t tell you her father’s name. “You know the Jackie Robinson story,” she says. “You should know the Kenny Washington story.” Washington, born in 1918, grew up in Lincoln Heights, an L.A. neighborhood then dominated by first- and second-generation Italian and Irish families. Railroad tracks framed one edge of Lincoln Heights, and many in the neighborhood found work on the trains. Washington’s grandfather was a cook on the local train line, which is likely how the family became the only Black residents of the neighborhood, according to friends and historians. Washington’s parents met as teenagers. His father, “Blue,” stood 6 foot 5 and translated that physical prowess into a Negro Leagues baseball career, along with bit parts in Hollywood films, including an uncredited role in Gone With the Wind. However, Blue reportedly squandered his money on women, booze and gambling. When Washington was 2 years old, his mother separated from Blue and moved in with Washington’s grandparents, uncle and aunt. Although Blue would resurface at Washington’s UCLA games, his boastfulness embarrassed Washington, who always saw his uncle Rocky as his father, writes Woody Strode, Washington’s teammate and best friend, in his memoir Goal Dust. Washington’s family had established a respectable community presence, bonding with neighbors who often faced prejudice as immigrants. His uncle Rocky was the Los Angeles Police Department’s first Black uniformed lieutenant. He’d joined an almost entirely white police force, combatting pervasive prejudice with an easygoing charisma that set an early example for his nephew. Growing up, Washington might have gained a false impression that he could be anything he wanted. A 6-year-old in overalls, Washington approached the coach of an all-white semipro baseball team in a nearby park, Gretchen Atwood writes in her book Lost Champions. Soon, Washington shagged flies for batting practice, stunning the coach with his arm. In high school, Washington played both baseball and football, routinely throwing passes more than 50 yards while leading his team to a city championship. He won the title in the Coliseum he’d one day consider his second home. Washington was recruited by the University of Southern California (USC), a football powerhouse, but he knew that the Trojans had recently recruited a Black high school star only to have him sit on the bench. Realizing that USC might merely want to prevent him from playing for a rival school, he signed on with the fledgling UCLA program instead.

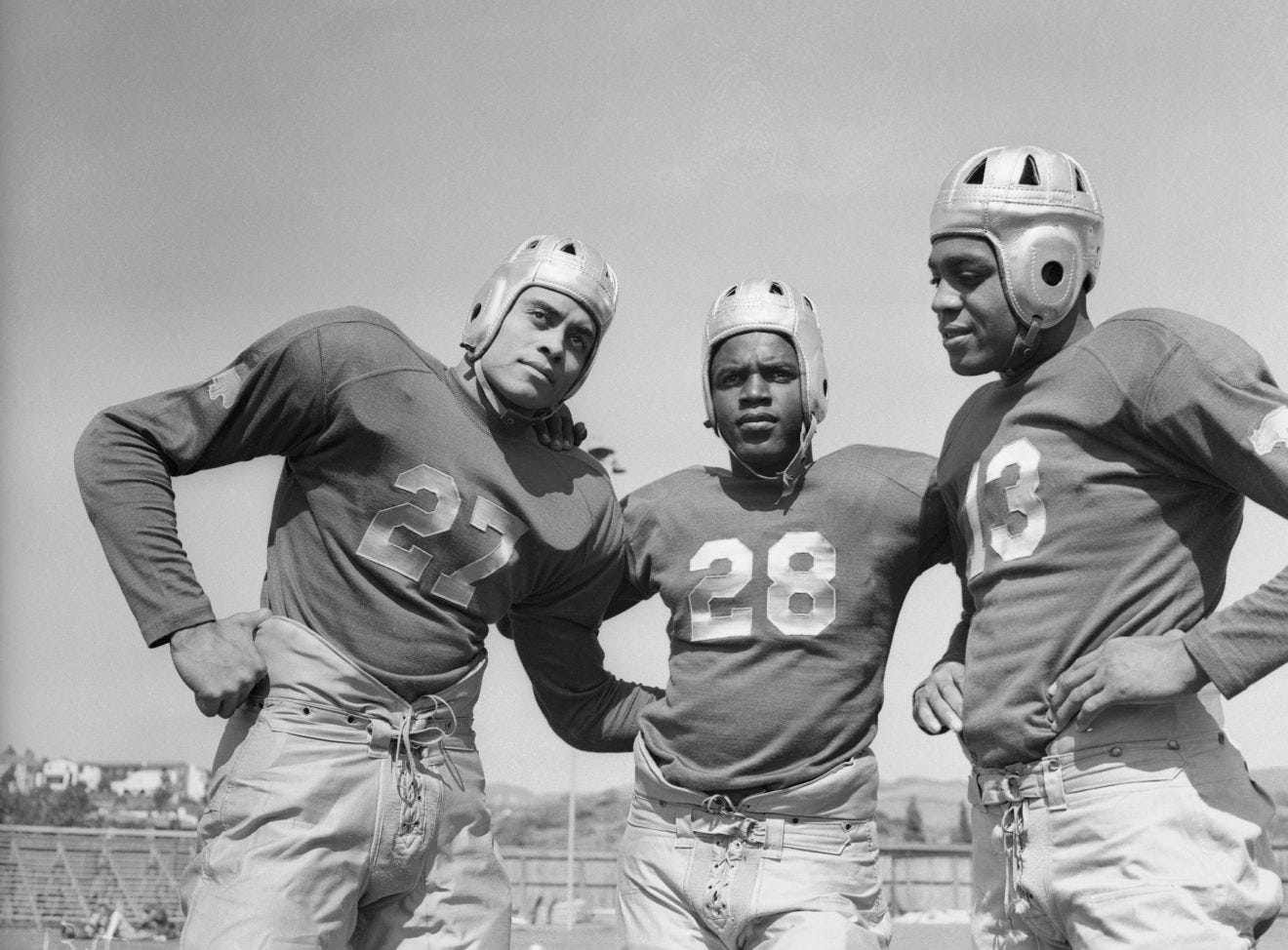

He was one of only a few dozen other Black college football players across the country. That included UCLA teammate Woody Strode, who lived in L.A.’s Central Avenue neighborhood, which fizzed with nightlife and music. In his memoir, Strode described how “the Black Sunset Strip” once saw luminaries like Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne and Duke Ellington light up the night. The Bruins treated Washington like a star too, Strode writes, providing him with a Ford Model T, although they put the car in Strode’s name because he was older. (Until a 1940 investigation into the recruiting practices of Pacific Coast colleges, incentives like these were rampant, and the schools and athletes took full advantage.) With Strode at the wheel, the California sun glinting through the windshield, they cruised the L.A. streets. Occasionally, the UCLA stars pulled up to a curb, turned up the radio, and jumped out to jitterbug. One afternoon, Strode hit the gas to make sure they weren’t late to campus. In the rearview, he soon saw LAPD siren lights. Pulling over, the young men knew what to do when the white police officer asked Strode for his license. “Hey, you know my uncle, Lieutenant Washington?” Washington said. The officer bent for a better look at Washington. He smiled and asked them to take it slow.

T he UCLA campus would also prove to be a relatively safe haven. In student government, Washington helped to address minor instances of racism in a swift, democratic style, Strode writes. On the football field, they battled initial prejudice among teammates, according to Atwood, and it took a series of one-on-one fights in practice before Strode earned the respect and eventual friendship of a troublesome bigot from Oklahoma. Washington won over teammates with his skills. Yet as their lives expanded outside of L.A. they encountered a level of prejudice beyond isolated incidents. Strode and teammates said that some would go as far as cheap shots like rubbing sideline chalk in their Black opponents’ eyes. In 1937, UCLA even faced a “tough guy” coach who proved to be a harbinger of the racism Washington would face from the most powerful figures in football. Washington State Cougars coach “Babe” Hollingbery holds the school’s record for most wins, has a campus fieldhouse named for him, and is enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. A disciplinarian, Hollingbery enforced rules against drinking, smoking and even cussing, and then unleashed his players after firing them up with his pregame speeches. Washington State, then a powerhouse, had defeated the Bruins in every matchup but one in the 1930s, yet in its first game against Washington and Strode, the Cougars found themselves engaged in a scoreless struggle. In college, Washington, 6 foot 1 and just under 200 pounds, played left halfback, a position that required a skill set similar to today’s best quarterbacks who pose equal threats to pass or run. “As a broken-field runner he had a straight arm that felled giants and a de-step that looked like an adagio dance,” described the L.A. Times. “Speedy and a good blocker, he also had a slingshot pass that for accuracy and distance surpassed anything Jim Thorpe ever threw.”

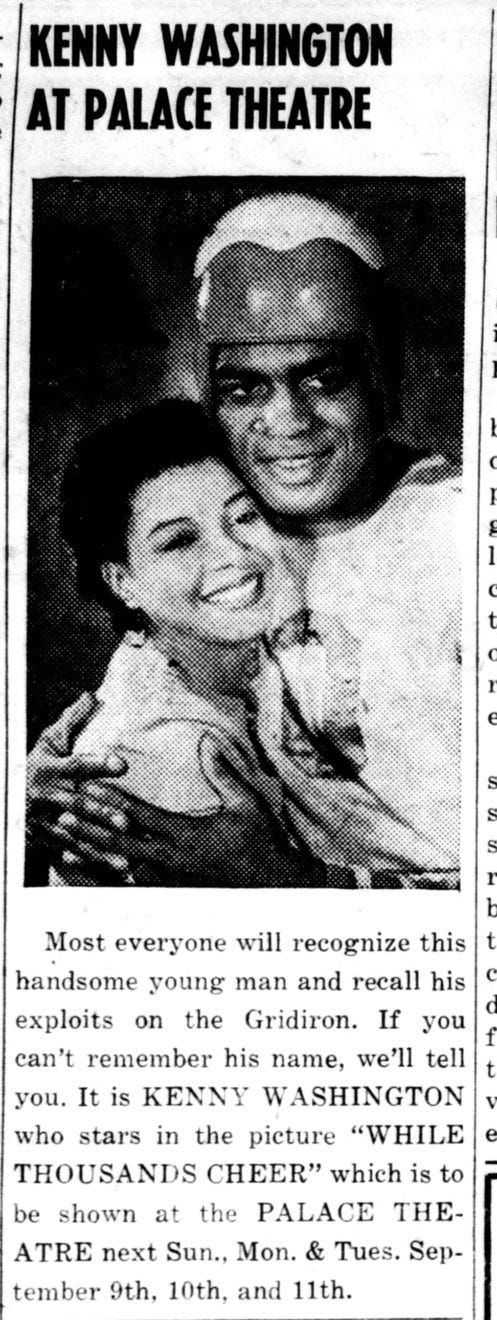

Washington touched the ball on almost every offensive play, and on a sweep against Washington State he tucked it away, sprinted around the lumbering defensive lineman and headed toward the wide-open Cougars sideline. A livid Hollingbery, easy to spot in his colorful hat and tie, shouted the N-word, according to Strode. Washington put his foot in the ground and cut straight toward Hollingbery on the bench. “Kenny swung on him. And it sort of turned into fisticuffs,” Strode writes. “But that’s how we were taught, to defend ourselves.” Washington State beat UCLA 3-0 on a late field goal; however, it would be the last Cougars win against Washington and Strode. And in 1939, the UCLA backfield added another supreme talent — Jackie Robinson. The future baseball legend was a four-sport athlete, running track along with playing basketball, baseball and football at UCLA. Washington, who also played baseball at UCLA for a year, performed far better on the college diamond than Robinson. In the one season they shared together on the gridiron, though, Robinson and Washington traded dazzling plays to lead the Bruins to an undefeated season and its first Associated Press Top 10 ranking, after a tie in the final game against USC. Washington, who played offense and defense, had been on the field all but 20 minutes in his senior season. Strode writes that his teammate’s body took such a beating on game days that Washington would visit the hospital afterward to receive intravenous glucose treatments. In his final game as a Bruin, Washington exited with 15 seconds left, allowing more than 103,000 USC and UCLA fans to stand together and roar, honoring his legendary college career. “It was like the Pope of Rome had come out,” writes Strode. Yet Washington hadn’t earned everyone’s respect, and the L.A. press was revolted when he was only named Second-Team All-American and snubbed from the East-West Shrine game — the college all-star game in which the West squad happened to be coached by Washington State’s Hollingbery. On the same day that Washington heard that last roar as a Bruin, all 10 NFL teams passed on him in the draft. In 1933, Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall pushed to ban Black players. A small group of Black players had helped start the league in 1920, but the number had dwindled to two before Marshall deemed them bad for business and a threat to jobs for white men during the Great Depression, writes Jeff Davis in Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas. All of the owners — including the legendary and powerful George Halas of the Chicago Bears — obliged the ban, which would last 13 years. After the 1939 draft, NBC sports commentator Sam Balter challenged owners to explain why they’d passed on Washington. “He would be the greatest sensation in pro league history with any of your ball clubs.” The ban remained an unwritten agreement, which owners would ignore, obfuscate or deny when pressed. Washington, however, did make another college all-star team, which played an exhibition against the defending NFL champion Green Bay Packers the following summer. Held at the Chicago Bears’ Soldier Field, Halas brought his whole team with him to scout for any advantage. In a goal line collision with a stout Packer, Washington bowled over Charles “Buckets” Goldenburg to tie the game. During a post-game interview, Goldenburg called Washington the “finest” player on the college all-stars. Halas couldn’t resist the possibility of having a talent like Washington on the Bears, offering to pay for Washington’s hotel if he would stick around in Chicago, according to NFL writer and historian Adam Rank. Washington stayed but Halas failed to persuade the other owners to let him sign Washington. “George Halas kept me around for a month trying to figure out how to get me in the league,” Washington said in 1970, as reported by Chicago sports historian Jack M. Silverstein in an article he wrote about the role Halas played in the color ban. “I left before he suggested I go to Poland first.” Instead of the NFL, Washington signed with the semipro Hollywood Bears. The team, which was billed as “Washington and the Bears,” drew thousands to the Coliseum, but Washington’s meager salary wouldn’t be enough to support his family. Washington’s wife, June, gave birth to Kenny Jr. in 1941, and Washington went to work for the LAPD like his uncle Rocky. He also took bit roles in movies, like his father had, including a part alongside his former teammate in The Jackie Robinson Story.

I n 1946, the NFL champion Cleveland Rams moved to L.A. Before an initial meeting about playing in the Coliseum, Leonard Roach, the president of the Coliseum Commission, tipped off the Black press. Halley Harding, a former Negro Leagues baseball player and editor for The Los Angeles Tribune, saw an opportunity. For years, Harding had derided the NFL’s blackballing of Washington, whom he called the greatest West Coast player ever. Fellow Black press tapped Harding, once a college debate team member, to speak at the meeting. According to Atwood, the commissioners gathered around a long wooden desk, and Rams general manager (GM) Charles Walsh, an imposing man, issued the Rams’ proposal, with revenue breakdowns. Harding jumped at his turn, striding across the floor and looking each commissioner in the eye, reminding them of the 1920 NFL, when small-town teams allowed Black stars like Fritz Pollard to attract fans to a game far less popular than baseball. More recently, Harding said, Black soldiers had fought in World War II, only to return home as second-class citizens. Finally, he landed on Washington, whose UCLA triumphs many commissioners had seen firsthand. Harding stopped before Roach. He demanded that the commission deny the Rams’ use of a public stadium unless the team gave Black players like Washington a chance. The Black press cheered. The commissioners nodded in approval. Walsh promised to try out Washington. On March 21, 1946, Washington signed a contract at the plush Alexandria Hotel in L.A. Flanked by GM Walsh and Walsh’s brother, Adam, who was the Rams’ coach, Washington wore one of the tailored suits that would become his off-field uniform. Two months later, the Rams signed Washington’s only choice for a compatriot, Strode. Then, before the rival All-American Football Conference (AAFC) league started its season, owner Paul Brown integrated his Cleveland Browns with future Hall of Famers Marion Motley and Bill Willis. Not surprisingly, Jackie Robinson and Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey kept close watch on this news. Although Robinson had played two years in the same semipro football league as Washington, he’d already started playing minor league baseball and recognized America’s pastime as his game-changing opportunity.

S trode’s and Washington’s careers with the Rams began with an infamous preseason road trip to Chicago to face the college all-stars. Washington returned from practice irritated, according to Strode. “What’s wrong?” Strode asked. “We can’t stay at that stinking hotel,” Washington said. The whites-only Stevens Hotel had given Washington and Strode each $100 to go elsewhere. Across town, they found the equally plush Pershing Hotel, whose lounge booked top jazz musicians. A large, multiracial crowd gathered that night to hear Count Basie’s music transcend color barriers. Washington and Strode found barstools and each ordered a Tom Collins. Around midnight, Rams’ quarterback Bob Waterfield, a friend of Washington’s, spotted them. “You crazy sons of bitches, what are you doing here this late?” Waterfield asked. Washington laughed. “Enjoying this club,” Strode said. “Look, we’ve made arrangements for you to come uptown with us,” Waterfield said. “Forget that,” Strode said. “I’m going to be segregated, spend this one hundred dollars, stay right here, and listen to the Count play his music.” Waterfield sat and ordered a drink too. Being on the field hardly proved as smooth. In their following game, an opponent tried to kick Washington in the head as he was lying on the ground. He dodged the blow, and when teammate Jim Hardy later asked him about it in the locker room, Washington replied, “It’s hell being a Negro, Jim.” The defending champion Rams fared little better over the entire 1946 season than in Washington’s first game, perhaps because they failed to use their new talent. Strode caught just four balls and concluded that he’d been hired primarily as a roommate for Washington when the Rams cut him before the next season. “Integrating the NFL was the low point of my life,” Strode said in a 1971 Sports Illustrated interview. “If I have to integrate heaven, I don’t want to go.”

As for Washington, the Rams neglected to use his cannon arm and converted him into a ball-carrying fullback. Although he only toted the ball 23 times for 114 yards his rookie season, he returned in 1947; without Strode he was now the NFL’s only Black player, and he reminded everyone of what he could do. Now 29, beyond his prime and guaranteed to always walk with a hitch because of knee injuries, Washington ran the ball 60 times for 444 yards for an NFL-leading 7.4 yards per carry. After being knocked out cold one game, Washington returned to break off a 92-yard touchdown run that still stands as the longest in Rams history. Washington would play yet another season, carrying 57 times for 301 yards. In an era with only 12-game seasons that saw teams share the load among many running backs, Washington’s numbers ranked him among league leaders. Yet in an ABC interview before his retirement, he said he was “tired” and had enough of “fame and bad luck.”

A moment near the end of Washington’s career illuminates what he meant by “bad luck.” In Sports Illustrated, Alexander Wolff chronicles Washington arriving for his penultimate game against the Washington Redskins. On a December Sunday, Washington stood outside the player’s entrance to Griffith Stadium in the still-segregated nation’s capital. Inside the stadium, the team’s marching band would soon play “Dixie” at the behest of its owner, George Preston Marshall. When moving the team from Boston, Marshall changed the team’s name from the Braves to the Redskins. And the “Hail to the Redskins” fight song included the lyric “Fight for Old Dixie.” Billed as the “Team of the South,” Marshall’s team would remain white until the U.S. government forced it to integrate in 1962, and the franchise would cling to its racist name until 2020. The gate attendant denied Washington’s entrance until another team official intervened. Washington caught one of five Rams touchdown passes in a 41-13 rout of the Redskins, yet he’d never go to another Rams game against Washington.

He died of polyarteritis nodosa, an inflammation of arteries, and spent much of his last three years at the UCLA medical center overlooking the Bruins’ playing fields.

Today, bronze busts of Marshall and Halas sit among the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s inaugural class of 1963, a halo of light glowing behind them. Meanwhile, Washington remains absent.

“It would be a shame if [Washington] were to be forgotten,” said Jackie Robinson, who would die a year after his UCLA teammate, writes James W. Johnson in The Black Bruins. “I know I never will forget him.”

Like Washington, his family is modest. Yet after learning more about her grandfather, Melanie Cohen gave a TED Talks–style speech at college titled “My Piece of Black History.” Like her mother, she questions Washington’s Hall of Fame omission.

Both the NBA and NHL have recently enshrined Black pioneers. In 2019, Chuck Cooper was inducted into the NBA Hall of Fame a year after Willie O’Ree joined the NHL’s Hall of Fame. Neither player was a superstar but instead entered hallowed ground based on shattering their leagues’ color barriers in the 1950s.

Saleem Choudhry, who heads the selection process as the Hall’s vice president of museum/exhibits and services, says a player needs five years of pro football experience to be included.

“We can make an exception though,” says Choudhry, who acknowledges that the Hall has discussed Washington’s candidacy. “It would have to be approved by our president.”

Writers such as Wolff and Rank have campaigned for Washington’s induction, and in 2016 a group of fifth graders in Central New York started a petition on Change.org that gained more than 12,000 signatures and was retweeted by the head of the NFL players’ union and several NFL players. During a project on civil rights heroes, one of the students, Kaylin Mazyck, had discovered that Washington wasn’t a Hall of Famer, so, along with his teacher, Liza Turner, he sent the petition to the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. No response.

“Bummer is an understatement,” says Mazyck, now 15, about Washington’s continual snub.

Regardless, Washington, whose daughter says she never heard him complain about racism, stands in a class by himself. For his last game as a Ram, anointed “Kenny Washington Day,” fans raised money to give him gifts including a car, a TV, and a trophy that Washington donated to his high school to honor its best player annually.

“Your cheers went to my heart but not to my head,” Washington told fans.

Geoff Graser is a freelance writer based in Rochester, New York, who also co-hosts and curates the Flour City Reading Series.

Brendan Spiegel is the Editorial Director and co-founder of Narratively.