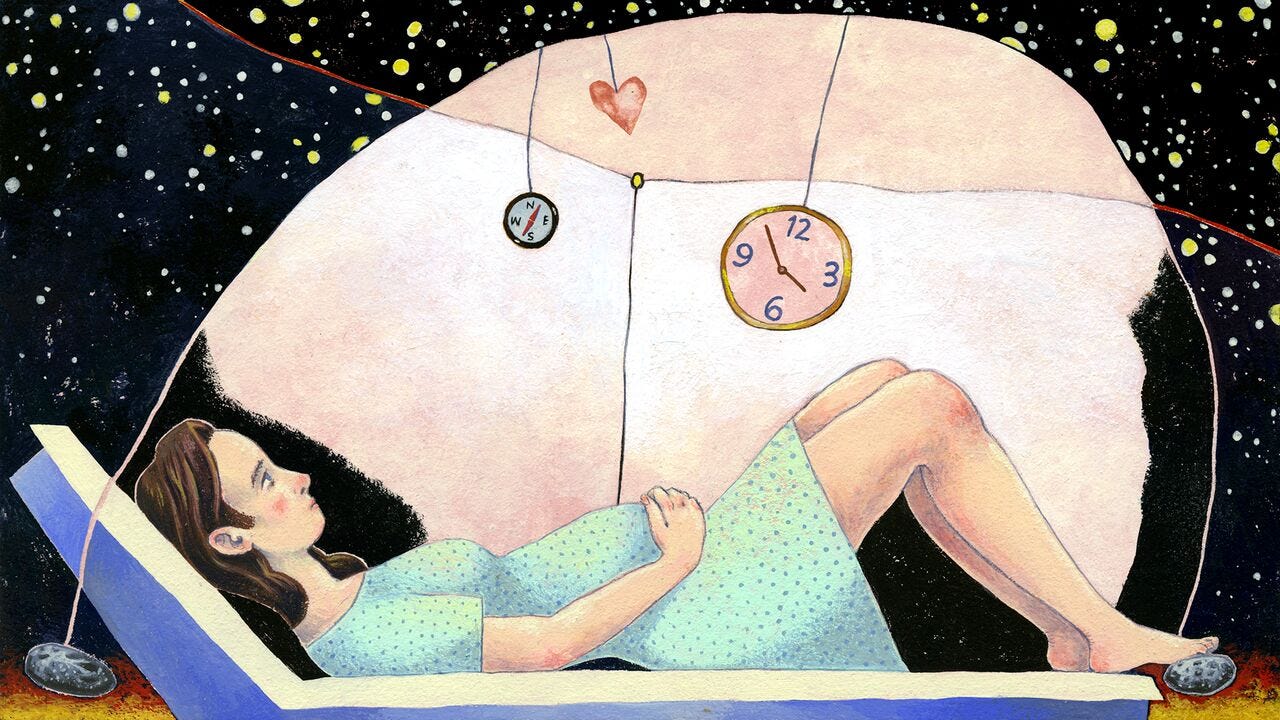

I Was 20 Weeks Pregnant When They Told Me My Baby Might Never Be Able to Walk

Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a child, I was told I should never have kids. When I finally did conceive, I ended up having to make the hardest decision of my life.

Illustrations by Amanda Konishi

Now.

My first instinct is to hop a plane to the pink palaces of Jaipur or the white-walled city of Dubrovnik. I put both trips on hold seventeen weeks ago when the stick came back with the smallest, fullest plus sign I’ve seen. Every muscle in my body readies itself; they want to run. Not to escape the reality of it all, but to deal with it my way, my restless feet itching for the next place I’ve never seen. Of course, running isn’t an option. My second instinct is to wallow, to bury my heart in a hole so deep the heavy, cool dirt will stop it from hurting.

There are no holes here. Here, in this wing, there are white walls, white tile floors, and white coats awash in gray light because no one has switched the fluorescents on or the monitor off. He’s still there on the screen, the butterflied end of his spine magnified on the ultrasound of my uterus. The doctor says his vertebrae is crooked and not fully fused on the final third of his spine. There aren’t e…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.