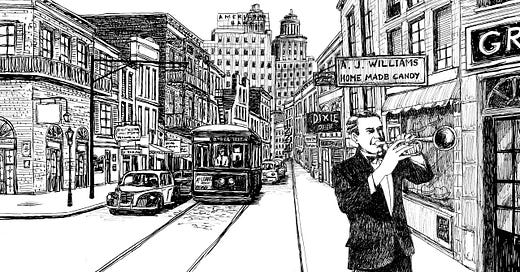

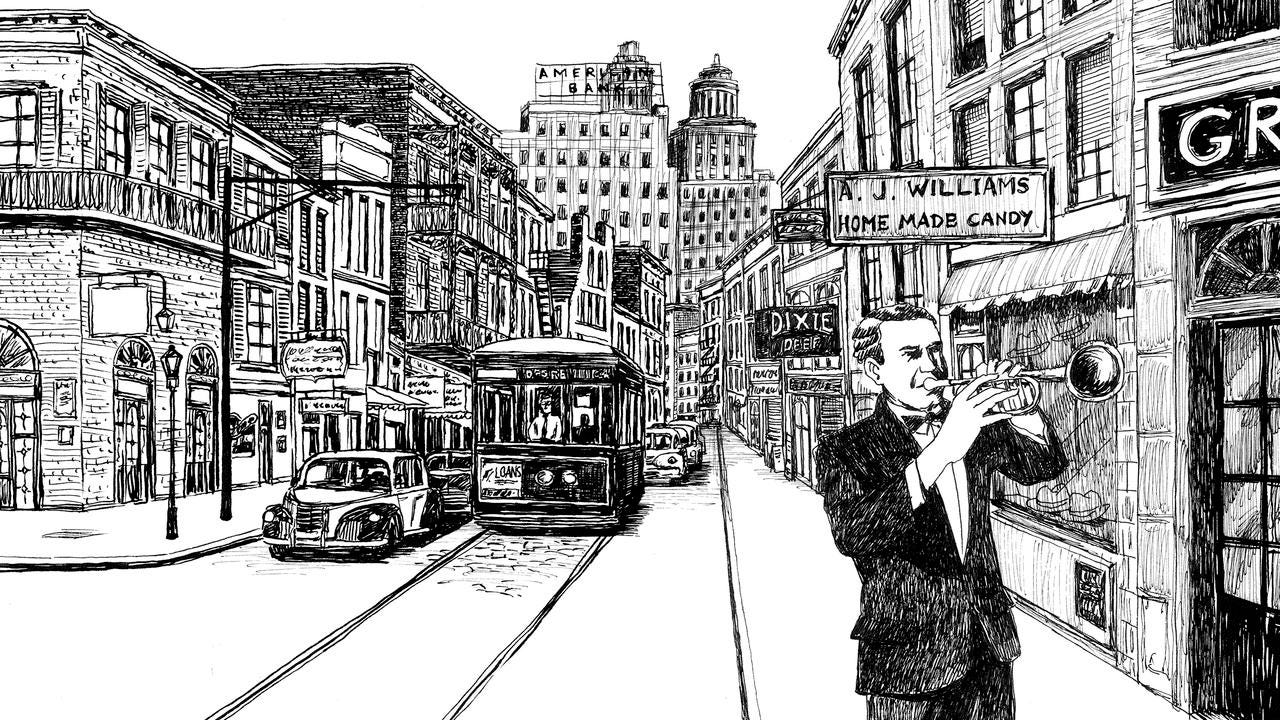

Jazz's Great White Hype

The family of a white trumpeter who claimed to have invented jazz demands he be recognized among the genre’s greats…but not everyone is singing the same tune.

Illustration by Pierre Dubois

Carol Tyner rolls up to the Old U.S. Mint in New Orleans in a beautifully restored maroon 1948 Mercury. She drives the car to promote the legacy of her father, Dominic James “Nick” LaRocca, a Sicilian-American cornetist, trumpeter and bandleader whose Original Dixieland Jazz Band was the first group to record jazz. As far as Tyner is concerned, her father’s not famous enough.

“I had to go out of the country to see my father!” says Tyner, who recently traveled to Sicily to see a bust of Nick LaRocca. “I visited the one in Salaparuta at the music center named after LaRocca. My father wasn’t raised there but his parents were. In Salaparuta he’s considered alongside Louis Prima. Then I went to Palermo and found the street named after him, and then went to the music conservatory there, which has another bust. But then I walk around New Orleans and a lotta people don’t even know who Nick LaRocca is.”

At the Mint — which has served as a museum dedicated to New Orle…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.