For a Magician Like Me, Conversion Therapy Was the Ultimate Illusion

My family wanted me to change so badly, I suspended my disbelief and tried to imagine I could.

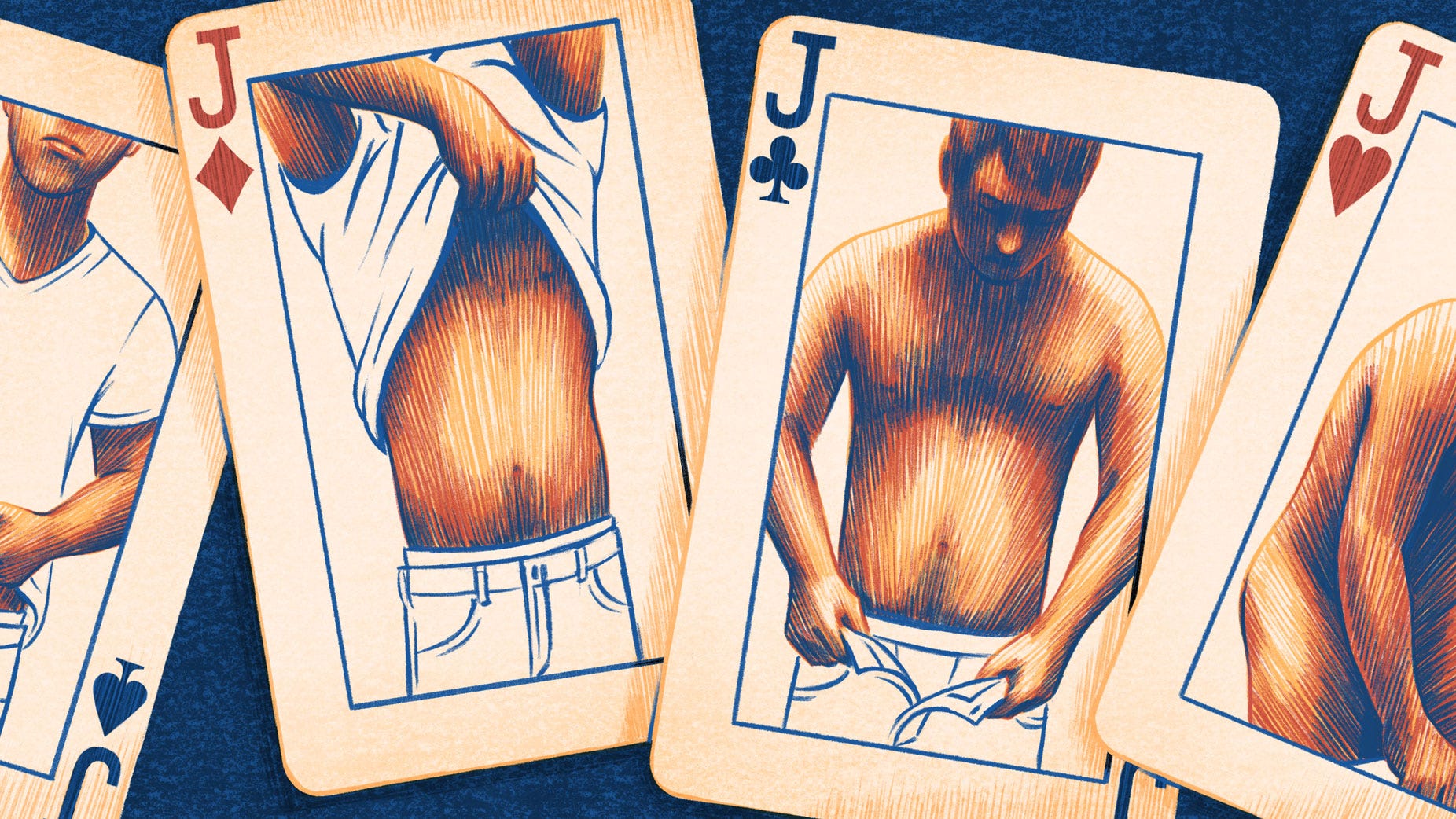

Illustrations by Brian Britigan | Edited by Lilly Dancyger

Vernon, a heavyset man in his late 50s, stood in the middle of our circle of eight men, dressed comfortably in loose-fitting clothes and a pair of beat-up Nikes. “What is your deepest wound around men and masculinity?” the counselor asked.

Vernon, whose name has been changed here to protect his privacy, shared that he had never felt he belonged among men because of his body. He said that he had struggled with body image issues since he was a young boy.

I was at a campsite in Pennsylvania for a 48-hour weekend retreat called “Journey Into Manhood” to help me change from gay to straight. I’d paid the $625 registration fee with my own money, signed a confidentiality agreement, and locked my phone in the car. It was 2009, and I was 21 years old. I had mixed feelings about being there, but I wanted to do right by my family.

This particular exercise, about facing painful, unresolved feelings, was called “guts work.”

The counselor explain…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.