Me and My Eggs

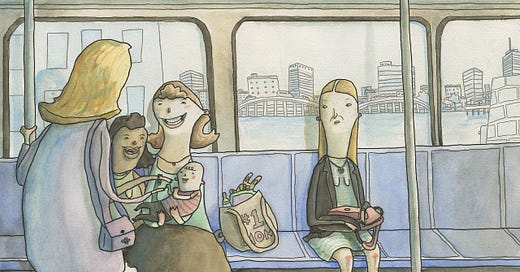

A baby-averse young woman finds her own way to help build a family—by giving a stranger her eggs.

At age eight, I cradled a tiny newborn baby in my arms for the first time while the young mother cautiously spotted me with her hands below mine. I would like to say it was an enlightening experience that illuminated the true joy of womanhood forever. I would like to say that ever since that moment I have had the alarming urge to smile at, wave to, long for, and hold all other women’s young ones. But the truth is the only emotions I can remember are nervousness, a slight sense of terror, and the eagerness to run back outside to play.

I knew this was not what I was supposed to feel. I was raised in a conservative part of the South, where a proud culture dictates that men should work hard to earn a living and all women should desire babies. After all, what else is there for a woman besides giving birth to another life and growing the family tree?

But I was the littlest of my Brady Bunch-style family—always trying to keep up with my older siblings and step-sibli…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.