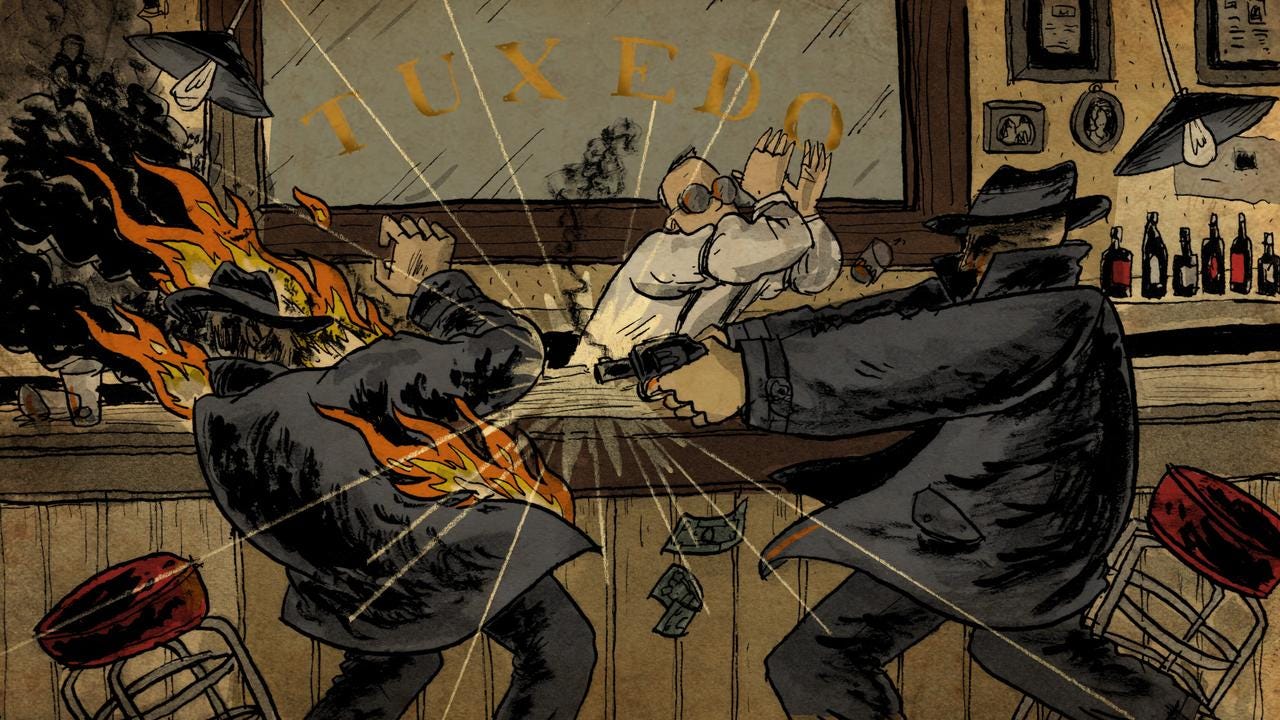

Murder at the Tuxedo

On Easter morning, 1913, the nation's most notorious red-light district was awakened by an epic gun battle, and a shadowy killer named Gyp the Blood.

Ever since the first flatboat sailor came down the Mississippi, loaded with cash and rotgut whiskey, New Orleans has been wary of outsiders. On Easter Sunday, 1913, a trio of New Yorkers learned that lesson well, when they found themselves in the center of a gunfight that forever altered the nation's most famous red light district. Driving the chaos was a man named Charles Harrison, better known as Gyp the Blood.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.