My Dad, the Globetrotting Businessman, Paleographer...and Spy?

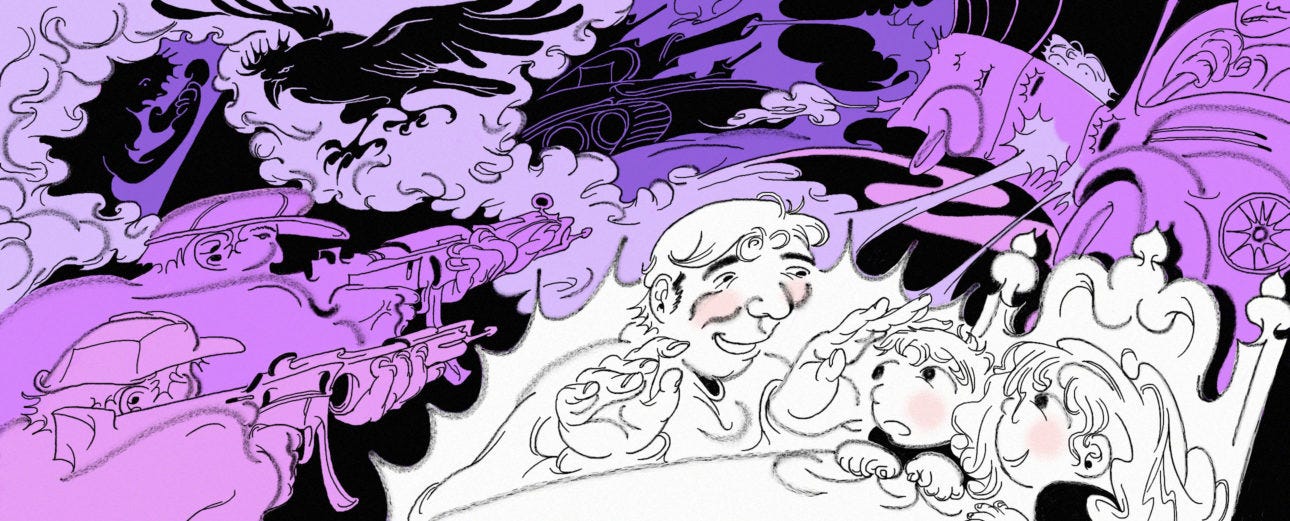

Growing up, I thought everyone’s parents told them bedtime stories about being chased by the secret police and dodging bullets. As an adult, I started to wonder just who Dad really was.

“When I came home from work, the cook told me that some men had entered the house with machine guns drawn,” my father recalled dramatically as he tucked me and my brother in to bed.

At bedtime, instead of reading us stories from the pages of fairytales or books of cartoons, my dad used to tell my twin brother and me stories about his own life. This particular tale was from 1972, when he was working in the tea trade in Bangladesh. He’d been in his early 20s at the time, living in Bangladesh just six months after the country had been partitioned from Pakistan following a bloody war.

Growing up, I didn’t know that it was unusual for a parent to tell stories from their own life when tucking their kids in, nor did I realize that most parents didn’t have the type of stories he did. But this is what we did, and we were engrossed by my dad’s nightly adventures in Colombia, Bangladesh, Germany and Lebanon. We even had our fan favorite sto…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.