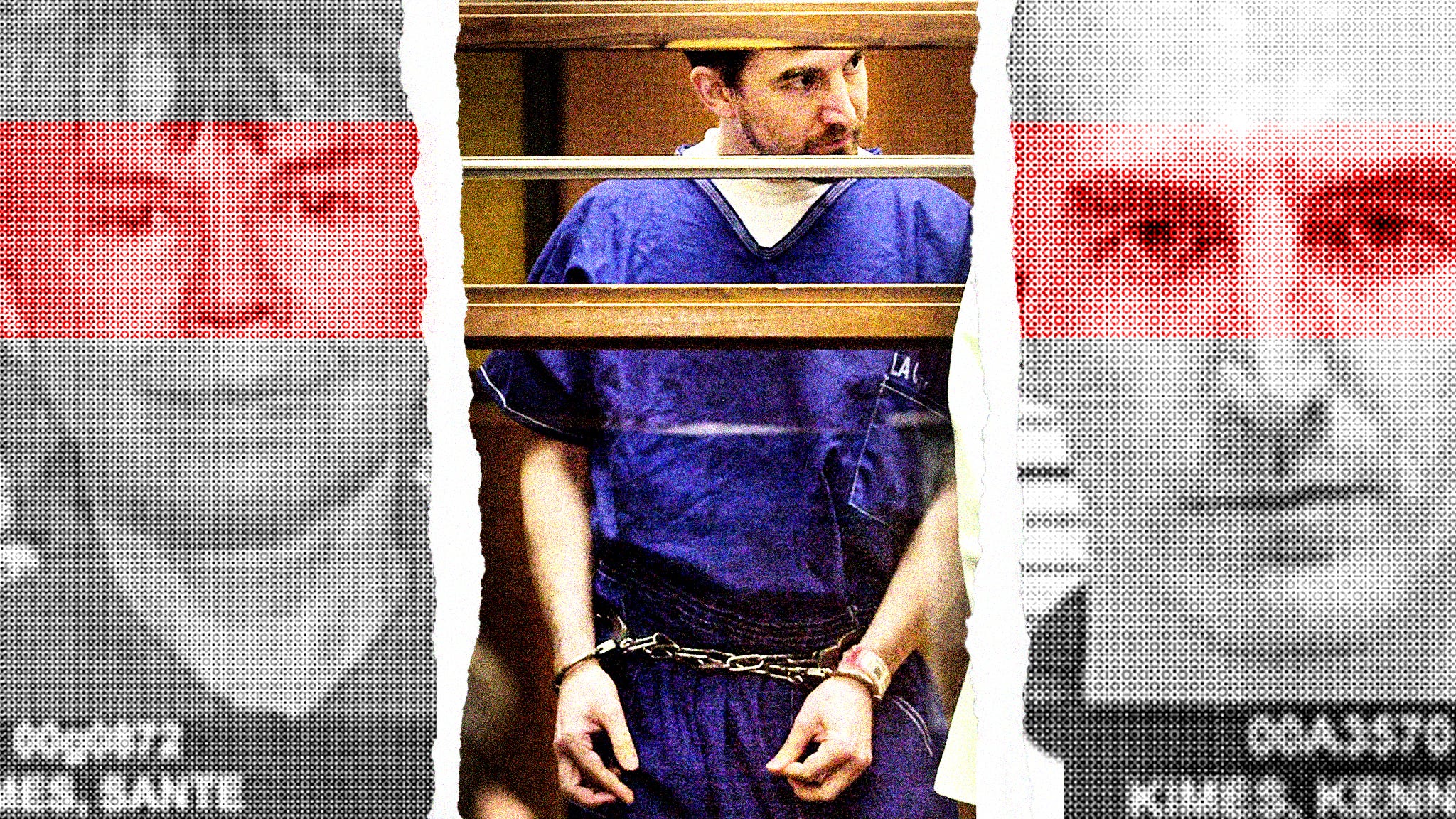

My Mother Taught Me To Kill

The tabloids called us “Mommy and Clyde.” This is what it was really like to be raised by a murderous sociopath—and how I finally found a moral compass behind bars.

“Do it, Kenny! Kill her! Do it, Kenny!”

I look up to see a slight foam in the corner of my mother’s mouth as she shouts these words at me. Funny the small details we focus on at the strangest times. Electric shocks from the Taser Mom fires into Irene bring me back to the task at hand. My hands are around Irene’s neck, and I can feel the electricity pulsing through this tiny woman as I strangle the life out of her. I am terrified, but I keep my hands around her throat. I don’t want to do this. I want to run. I want to jump on a plane and get as far away from New York City as I can, but I stay committed. Focus, Kenny. Remember. Family is everything. Always.

There is a thick tension forcing all the space out of the room as I feel her life slowly leaving. Then it is over, and there is silence. Irene lays dead in my hands. She is so fragile. While my hands commit murder, my mind wonders if my father is with us now — if he will meet Irene on the other side and hang his head with shame.

Mom tells me to put Irene’s body in the bathtub, and I do as I am told. We are in a desperate race against time, and I find comfort in familiar feelings of chaos and panic. I’ve been trained since childhood to shut it all out, push it away and react only to each moment as it comes. We have a plan, and it needs to be executed.

We put on gloves and bring bags. Irene owns the mansion we are standing in. After the death of her husband, she converted it to apartments, then made the costly mistake of renting me a unit across from her own. Her key ring has like a hundred keys on it. It takes forever to find the right one for her front door. When we are finally inside, my mother begins rifling through everything in Irene’s apartment. She looks for identity information, her Social Security card and passport: all the things needed for my mother to become the owner of the building. First, we took her life. Now Mom will take her identity and assume ownership of Irene’s multimillion-dollar Manhattan mansion.

Once we find everything, we return to my apartment across the hall. The body remains where we left it. It does not escape my mind that she has already become an it. My mother directs me to put the body in a duffle bag. Her tone reminds me of how she spoke to me as a child: “Kenny, get to bed. Kenny, brush your teeth. Kenny, put the body in the fucking duffle bag.” I do as I am told. The obedient son. Always.

Only after I maneuver around the numerous surveillance cameras to put the duffle bag with the body into the trunk of our stolen car do I exhale, and then only for a moment. I go back inside and find Mom running around the crime scene scrubbing it clean with rubbing alcohol. When she is satisfied that it is spotless, we finally leave. Once outside, in the fresh air, we wander the city. With Irene’s body secure in the trunk of the car, we head over to Trump Tower in Midtown to get something to eat at Trump Café.

We sit at a table drinking coffee and eating pastries. How fucked up is this? A woman was murdered by the same hands now wrapped around a cup of coffee. I stare out the window and watch an unaware city rush past as if nothing has changed. Can they not sense that something horrible happened a few blocks away? Do they not feel it in the air? When the girl gave me change for the coffee, her hand touched my own. Would she have recoiled if she knew what these hands were capable of?

Finally, my mother breaks the silence by reaching across the table and pushing the hair from my face. She tells me she is proud of me for killing Mrs. Silverman.

“You did good, Kenny,” she says.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.