One Man’s Daring Escape from Mao’s Darkest Prison

In 1958, thousands of Chinese citizens were sent to brutal labor camps where escape was impossible—but that didn't stop one man from trying. Now, his story is finally told.

Translated by Erling Hoh

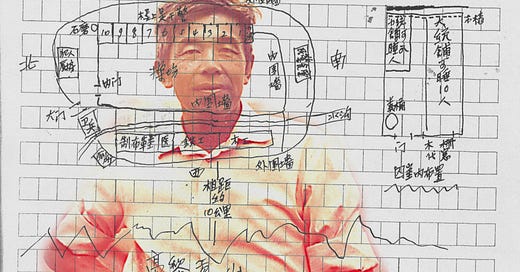

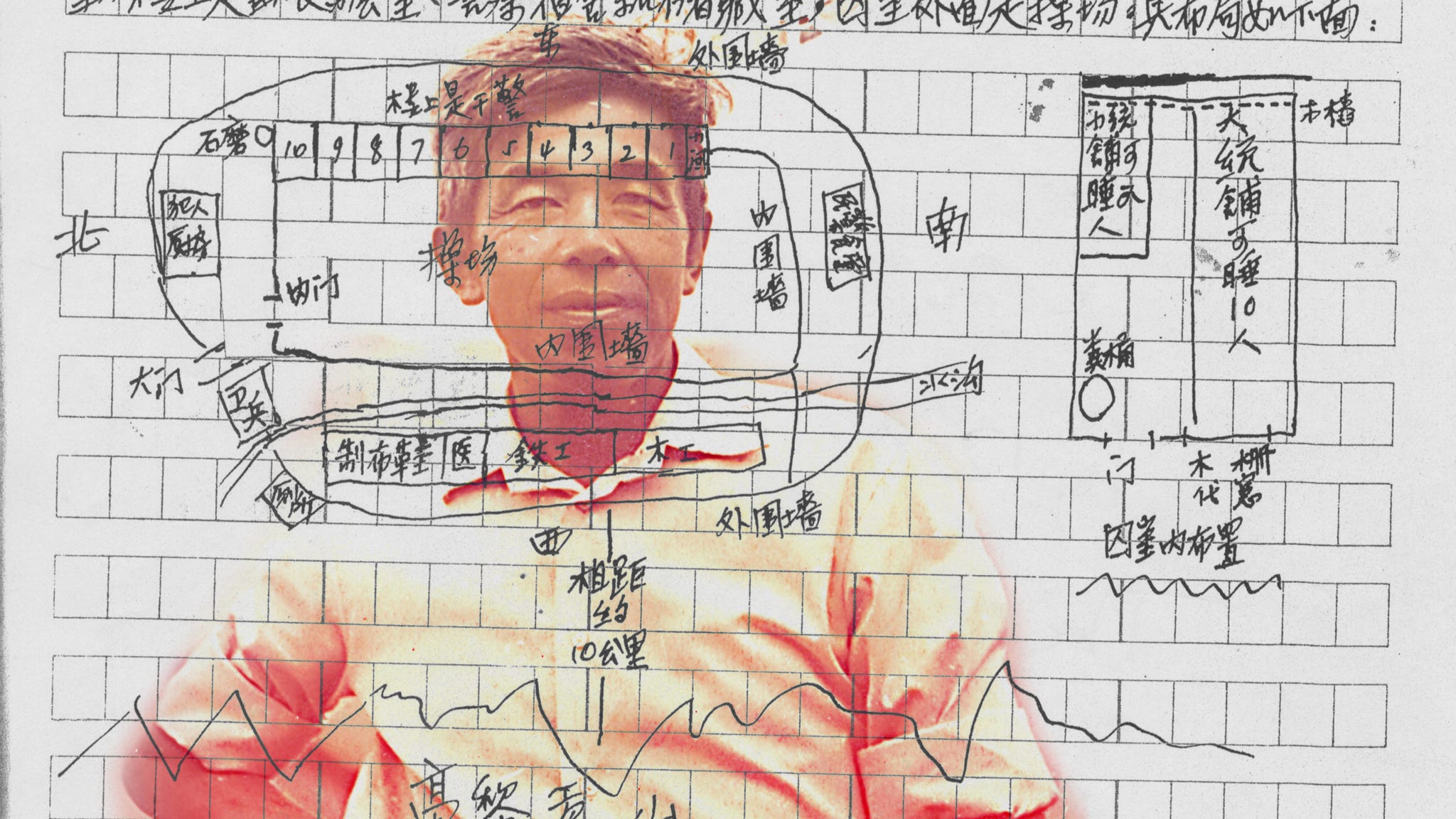

In 1958, as part of China’s Anti-Rightist Campaign, 550,000 Chinese citizens were convicted of crimes against the state. One of them was Xu Hongci, a medical student arrested for speaking out against the Soviet Union, who was sentenced to a camp called White Grass Ridge. For eight months, Xu worked up to nineteen hours a day on a starvation ration, each day growing closer to death. Finally, he and his young friend Chen Xiangzai attempted the impossible: escape. More than one thousand miles from the nearest land border, in a country as tightly controlled as any prison, it was an impossible journey, and one they had no choice but to make. Xu, who died in 2008, told his story in an unpublished manuscript that was discovered in 2012 by journalist Erling Hoh. This month, “No Wall Too High” was published in English by Sarah Crichton books. The following is an excerpt.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.