Black Girl, Blue Leotard: How My Ticket to Belonging Broke My Heart

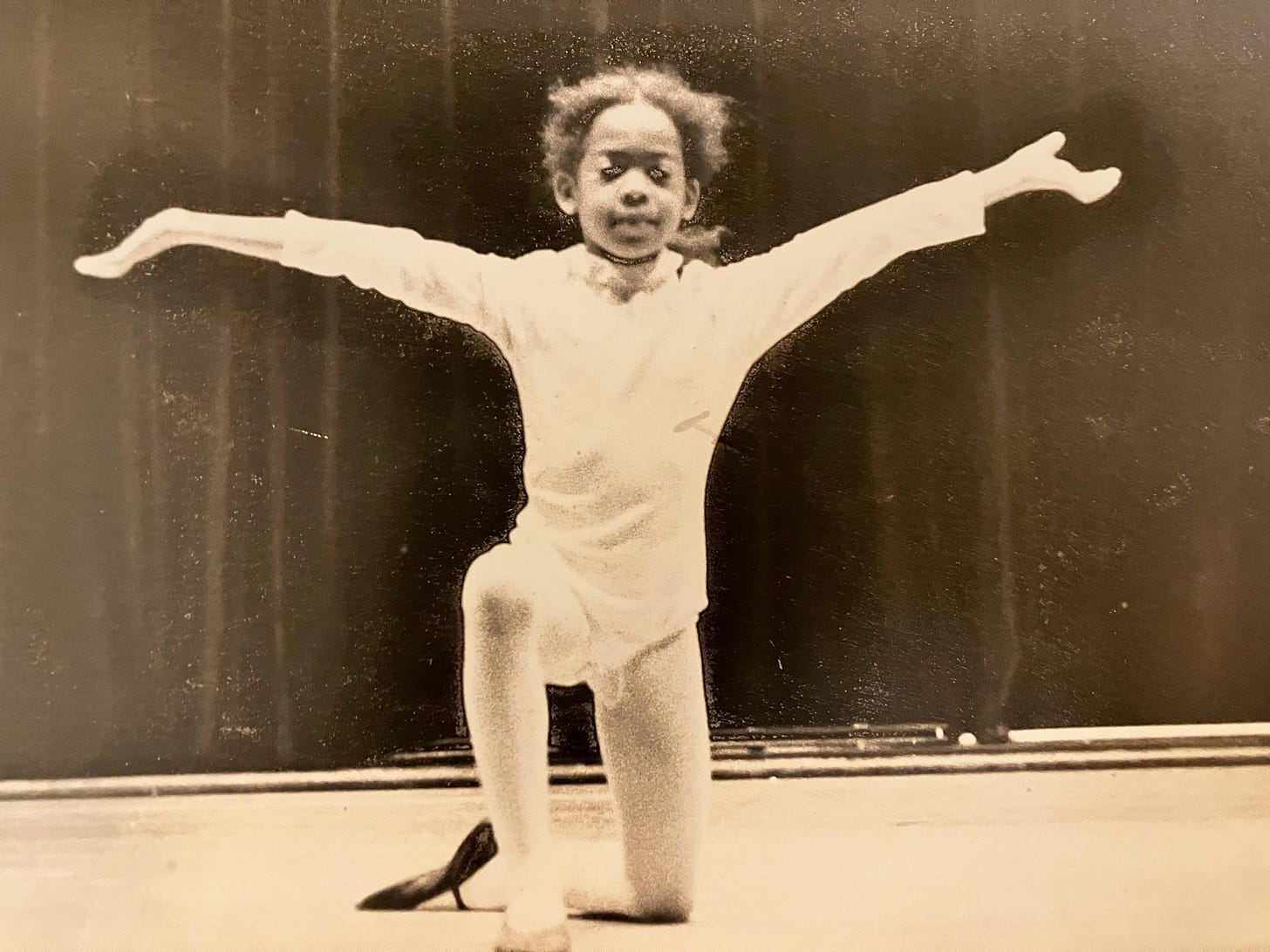

Lisa’s dance uniform was everything. She cherished it, wore it everywhere. Until, that is, she took a new dance class where she felt inferior and started to see things in a different light.

Our Memoir Prize contests are one of our favorite things that we do, and we’re so excited to finally present you with the grand prize–winning essay of our 2024 Memoir Prize, by Lisa Williamson Rosenberg. This is what Lisa had to say about how her stunning piece came to be: “The essay came from something I wrote on my father’s typewriter decades ago. I was trying to capture the memory of Charles Kelley’s dance class. Of course, I only had one copy of it, and I lost that. However, the feelings associated with the memory never faded, and as an exercise, I decided to re-create the whole thing from scratch.” Congratulations again, Lisa! And readers — enjoy. This one is a real beauty.

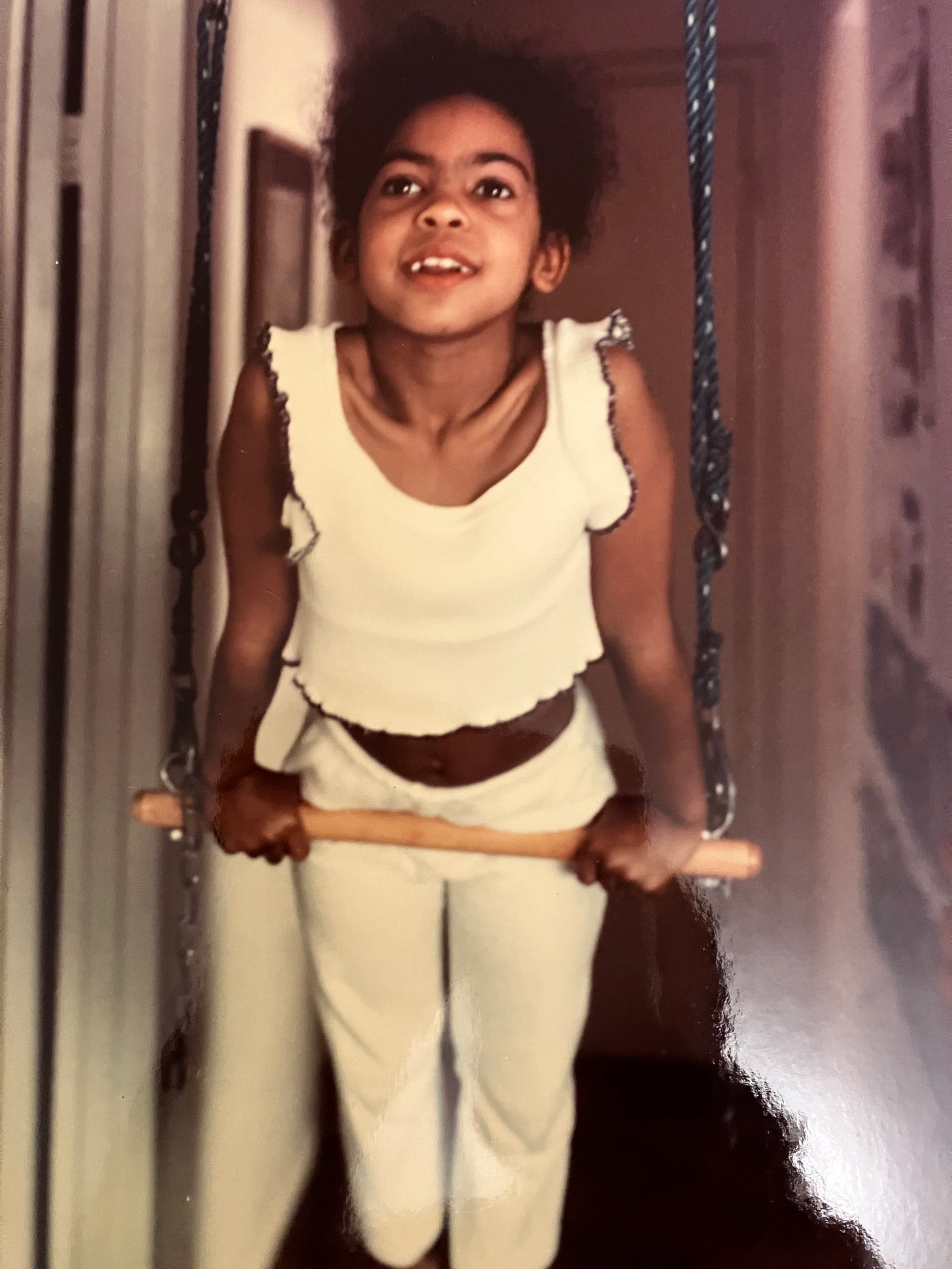

I loved my royal blue, capped-sleeve leotard more than you can imagine. Or maybe you can imagine it. Maybe you, too, were an only child of older parents, neither of whom you resembled because your father was Black and your mother was white and Jewish. Maybe, while you looked a bit like your father’s mother and, in some lighting, a tiny bit like your mother’s father, you looked nothing like anyone living. I had never heard of royal blue before then, but it was the most beautiful color I had ever seen: rich, bright and a tiny bit bluer than blue.

The leotard was my very first uniform, my first ticket to belonging. I got it when I was 6 years old and the brand was Danskin, which meant that the material was very thick and kind of itchy, but it was the leotard we were all required to wear for our modern dance class, to be held weekly in the basement of the 92nd Street Y.

I remember the very first class. And the dressing room — buzzing, bustling with other little girls and their mothers, a few of whom were also wrangling toddlers and bouncing infants — as jackets and street clothes were removed to reveal the brilliant shade of blue we all shared.

I remember a procession — of girls in leotards, our mothers, the several small siblings — to the place where we would meet our teacher and ostensibly dance. It was a vast space where most things were a classical 1970s brown: hardwood floors in need of revarnishing, smooth wood-paneled walls disrupted only by broad, stout windows with panes of the same brown, a stage that rose above it all with sepia-toned curtains pushed to the sides. There were folding chairs lined up against the walls where the mothers could sit and watch the class if their younger charges allowed it.

Our teacher — tall, fair and striking in a black leotard and beige footless tights — introduced herself as Kellyann. As we girls followed her to the stage, I admired the way Kellyann’s neat blonde ponytail bobbed and bounced against her neck. My mother, whose hair was straight and fine, dependent upon a nightly pin-curl ritual for “body,” was ill-equipped to manage my own mass of wild, coily tresses. I yearned for hair that my mother could do, or alternately, for my mother’s fingers to master the hair I had. I’d have been just as pleased with the multitude of braids I saw on the heads of Black girls with Black mothers.

Kellyann called us “girls” rather than “ladies,” as my subsequent dance teachers would. Her voice was soft yet commanding as she invited us to sit in a circle, feet together, knees bent and flopping sideways like frogs, which everyone could do and did proudly. Kellyann placed a record on the phonograph and joined us on the floor. With a warm smile and encouraging nods for all, our new teacher made it easy to follow her instructions and movements. We bounced our knees, we stretched our legs, we pointed and flexed our feet. Next, we rose like blooming sunflowers. We reached for the sky, stomped around like elephants, zoomed like dragonflies, arms like buzzing wings. We stole glances at one another throughout, studying each other — not with judgment but with rapt curiosity at our differences. We came in all the various colors, sizes and shapes of 6-year-old girls.

What a thrill it was! Belonging to and with these other girls: to and with the dark-skinned Black girl with pink airplanes on the end of her braids, to and with the redheaded white girl who had one big front tooth on its way in, to and with the girls who were twins with jet-black pigtails on the sides of their heads, to and with all the other girls in the class. We. That’s right. We wore royal blue, capped-sleeve leotards that were thick and kind of itchy. We. And that included me.

We were chickens. We were dolphins. We were cats. We were horses. We were silly. We tried but sometimes failed to avoid bumping into one another, which led to raucous laughter. We slid. We sweat. Our breath came in frenetic pants, giddy as our giggles. Then we moved slowly, slower than felt possible, as if through honey, with long steps and lunges, feeling our way through some imagined muck. We did not want the class to end, but by the time it did, we girls were — in a small, sweet, royal blue way — kin.

I often wore my royal blue leotard when I didn’t have to. In the summer, my mother would drive me to Scarsdale to feed the ducks, or to Brooklyn to visit family friends, or to Englewood, New Jersey, where we had guest passes to our friend’s community pool. I remember drowsing my way into naps in the back of our Buick Skylark, noticing the sun coming through the window and landing on my belly, where it created a warm diagonal beam, making two distinct shades of royal blue. Through the lashes of my drooping lids, I’d admire it, musing about whether the other girls from my class had their leotards on as well. I’d fall out of consciousness picturing us all marching arm-in-arm, our leotards marking us as one powerful 6-going-on-7-year-old body.

Mom liked buying my clothes “a little roomy” so I could grow into them. Which meant that the royal blue leotard still fit a year later, when I’d said goodbye to Kellyann and begun actual ballet classes with one Mrs. Rosenberg (no relation) in the old McBurney Y on West 63rd Street, around the corner from the Ethical Culture School, where I attended second grade.

The thing I remember most about Mrs. Rosenberg was that she always kept a bottle of Robitussin cough syrup on top of the piano and swigged from it as she taught. I never once heard her cough. Midpoint through the class, between barre and center work, Mrs. Rosenberg would shout, “Water break!” and we’d race out of the studio, down the hall to a water fountain, taking turns guzzling at the feeble spout, giving our teacher a moment to herself.

By the time we did our réverénce at the end of class and said goodbye, she was often rather tipsy. But despite her tippling, Mrs. Rosenberg helped ignite my love for ballet, even as many girls my age were already getting past the “I wanna be a ballerina” stage, turning to activities such as horseback riding (for those who could afford the Central Park–based Claremont Riding Academy) and gymnastics, which were somehow deemed cooler, or at least less “girly” than ballet. Publicly, I did strive to be a gymnast. Ballet, I told anyone who asked, was to support my gymnastics training, such as it was. I’d watched the Munich Olympics a year earlier and was quite taken with Olga Korbut, the famed Russian gymnast. I took gymnastics lessons, also at the Y, and thought I was pretty good at it. (Yes, I wore the hell out of my royal blue leotard there too, thank you.) I even got my mom to try to harness my free-form biracial hair into those two little sprigs of ponytail Korbut sported beside each ear.

Since my parents had had me “later in life,” my mother’s friends had much older children. The seasoned mother-friends made up a cadre of consultants brimming with advice for my mother and recommendations for enhancing my life — especially regarding my prime interests of gymnastics and dance. All of my teachers had informed Mom that I had talent and should move on from Y classes into “higher-caliber training programs.” I imagine I took my mother’s zeal for granted and let the research go on without my input. Being 7, I was still on a need-to-know basis with my personal agenda. Mom would tell me a week ahead about an upcoming activity and then remind me a day in advance, which was perfectly fine, as long as I could wear my royal blue leotard.

At this point, in case you are under the erroneous impression that I was some great prodigy, allow me to clarify how much talent I actually had. I was flexible enough, coordinated enough, my feet pointed enough. I had what dance teachers called “the right physique,” meaning I was thin (enough) with long legs and fine bones — the latter not being ideal for gymnastics, but I had loads of heart. I was eager to learn things, to do them the best I could and to make that best better. But the biggest thing for me was that it was all great fun. And when you are 7, you want things to be fun. This meant that when my father put on any record at all, be it Rachmaninoff, Aretha Franklin, the Weavers, or Bill Withers, I’d up and dance. (Our downstairs neighbors were a kind elderly couple whom my mother had made a point of befriending back when I was a block-dropping toddler.)

All our furniture became gymnastics equipment. To keep me from swinging on things that shouldn’t be swung on and balancing on things that shouldn’t be balanced on, my parents bought me a portable balance beam that fit under the couch when it was out of use. My father’s chin-up bar, which lived in the doorway of my bedroom (his erstwhile art studio), was converted to hold a mini trapeze perfect for doing tricks on. Are you getting the sense that ours was a child-centered home despite boasting just a single child? Understandable. My mother, an avid disciple of Dr. Spock and his famed Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, was an elementary school teacher who, at that point, was teaching education at Brooklyn College. As for Dad, though he had not considered having children until he and Mom had been married 15 full years, he possessed a wonderful silly streak and adapted easily upon my arrival.

In any case, because I had not yet moved into any “higher-caliber training programs” and was still dancing and tumbling at the city’s myriad Ys, I was accustomed to being — no other way to say it — the best in the class. And I’ll admit, that was fun too.

I don’t know how it was recommended to my mother, or who recommended it in the first place, but one day, Mom learned through her network about a dance and acrobatics class held in a studio somewhere in midtown. This class was taught by Charles Kelley, the world-renowned dancer and much beloved instructor, whose skills, we’d soon learn, though wide-ranging, did not include any capacity for interacting with a 7-year-old with far less talent and experience than her mother believed she had. My mother signed me up for one class with the maestro after being assured by some friend whose older daughter, also a dancer and gymnast, adored Mr. Kelley and swore that the class was open to people of “all ages and levels.”

Perhaps a more accurate description might have been “one level” in a manner similar to the retailer Brandy Melville’s “one size.” The store in question has never claimed that “one size” fits all, only that it carries just one size (corresponding to about a zero, according to most accounts) that either fits you or doesn’t. Regarding Mr. Kelley’s “all ages and levels” dance/acrobatics class, I was neither the age nor level anyone had in mind. The fun was about to end.

All I had going for me on the day of the class was my royal blue leotard, which would prove insufficient to shield me from a humiliation I still hold in my bones more than half a century later.

For starters, we were late. It was not like my mother to be late. Or certainly not since meeting my father, who was, in my mother’s words, “a stickler about time.” Dad, a Black man who had never heard of CP time, didn’t tolerate lateness and had cured my mother’s tendency early in their courtship. (The second time she was late for a date, he simply left. It never happened again.) But it was not unlike my mother to have read the time of the class incorrectly. When we arrived at the dance studio, we were directed to the women’s dressing room, a vaguely odiferous space full of iron hooks draped with bags and pointe shoes and other dance-related paraphernalia. Along the sides of the room were benches populated with lounging, smoking, dramatically made-up young women. All were white, as far as I could tell. All were sinewy with muscle, bone and blue veins visible through taut, pale skin. They were speaking in low tones — gossiping, perhaps — but paused the discussion briefly to regard us as we crossed the threshold. Apparently unimpressed, they dragged on their cigarettes, blew smoke into the already cloudy air and resumed their chatter.

No one smiled, which unnerved me. It was my first clue that this was not the sort of child-centered environment to which I was accustomed. My mother was the only mother in the dressing room. I was the only child. As Mom helped me fold and hang my outerwear, revealing me in my pristine royal blue casing, I observed sweat on the brows of the smoking, gossiping women. One rose, shouldered an enormous bag, blew kisses at the rest and departed. At this point, my mother and I understood that these dancers were not waiting for the class I was to attend but were instead cooling down following the previous class, meaning my class had already begun. The very next moment, I found myself ushered into the studio where I was to have reported 10 minutes earlier.

My entrance coincided with a profound hush, during which I became aware that the music, which had been playing on a turntable, had stopped. Other sounds — the thudding of feet, the swishing of chiffon and wool against nylon, grunts of effort — ceased as well. The studio was dimly lit, packed with bodies, each with a corresponding image in a mirror that lined the front wall. I could not see myself past the heads and bodies of the other members of the class. I was the only one with no mirror twin. The odor, a mix of perfume, vinegarish sweat, hair tonic and cigarette smoke that had been vague in the changing room, was pungent here in the studio. It was a withering, powerfully adult smell, a smell of experience that far exceeded my short lifetime. The next sound we all heard exploded like gunpowder from the barrel of a long, accusatory finger extended in my quaking, royal blue direction. Mr. Kelley’s voice.

“You’re late!” He stepped toward me, until the finger was several inches from my small, brown nose. “No one comes to my class late!”

Everyone stared. A few of the dancers tittered behind their hands. At this point, my mother, still in the doorway, stuck her head in to pipe up something about traffic, which brought about uproarious laughter from everyone in the room, Mr. Kelley included. It’s the first time I remember being embarrassed by my mother. The first time I remember being the butt — rather than the adorable object — of adult mirth. A dubious rite of passage. The shame — of being late, small, bewildered — hung around my shoulders and dulled my intellect.

Like the maestro’s finger, everything in the studio seemed designed to identify me as an interloper. What did not help was my once-trusty badge of membership: the royal blue, capped-sleeve leotard. How brashly it stood out against the others’ dingy grey, weathered maroon and black sweat-stained attire!

Once the dancing had resumed, I shrank back against the barre lining the wall opposite the mirror. Though we did not do warm-up exercises at the barre during this dance class — or perhaps those had been completed before I arrived — the barre itself was at least familiar to me. I was accustomed to beginning ballet classes at the barre, holding on with my left hand to perform exercises with the right leg, then turning to do the other side. There was a comfort to that, a sense of homecoming that I still feel any time I take a ballet class anywhere. The barre is where you start, where you collect your dancer identity, where you remember who you are. The barre is also where you stand during the “center” portion of a dance class, when your group has completed an exercise, and the next group is taking its turn. The presence of a barre is what makes a dance studio a dance studio: It is a dancer’s home base in more ways than one.

On the other hand, if a dancer — particularly a tiny 7-year-old dancer — must reach up for the barre, rather than gently downward along the natural angle of her shoulder line, then that barre is not for her, not a home base at all. The little dancer must find a lower barre that suits her proportions. The problem with the barre to which I now clung was that it was level with the top of my head. Like everything else in the studio, the barre sang of my reject status.

As I reached up to grip the barre with both hands, two men who had completed the current combination, backed up to make room for the next group. They did not turn to make sure their path was clear of small bodies and were aimed right for me. I dared not dodge, which would have placed me in direct jeopardy of being squashed by one or the other of them. Instead, I willed myself to shrink even smaller, praying that they would miss me.

Indeed, the men ultimately settled on either side of me, close enough to each other to make room for other dancers along the barre. Since the barre was an appropriate height for medium-sized grown men, the two were able to rest their hands on the barre at a downward angle along their natural shoulder lines, forming a canopy over my head. The men were so close, it was clear that they had no idea I was there, flanked by their armpits, their scent permeating the small field of air I had to breathe. There was no escape. I clung white-knuckled to the barre, at once longing to be saved but terrified that someone would notice that I existed and needed saving.

It was the maestro himself who noticed me. He leaned forward, hands on hips, directing his baritone once again at my person.

“Why don’t you dance?” he asked. “You come to my class late and don’t dance?” Now he stood straight again, still glaring at me. “You think you’re too young to dance in my class? Ha!” And then, turning away from me, said, “Jane?”

All at once, the mass of adult, black-, gray- and maroon-clad bodies parted. There, in the center of the studio was an image that should have given me hope, a sense of companionship and even belonging: another little girl. She was about my age, but instinct told me that her presence would provide no comfort. The girl was taller than me, thinner than me, with a long neck and sloping shoulders, shaped more like the lithe adult female dancers than any child I’d ever seen. She wore a white leotard with gently puffed sleeves that showed off her slim form. Her blonde hair was parted down the center and fastened into two round topknots. She was white, a shade of pale peach scarcely darker than her leotard.

Rereading what I’ve penned above, I can’t help noticing — as you may have noticed too — that I’ve mentioned Jane’s svelteness twice. That is how it hit me. I noticed her slimness more than her whiteness. So well had I been taught about the importance of thinness, the curse of body fat, how more or less of the latter impacted your acceptability — not only for dance and gymnastics, but for existence — that such assessment and mental categorization was automatic for me. This was not the first time I had compared my body to that of another kid. But I knew where I stood in my Y classes. I was thin, one of the thinnest, though strong enough to pull off the skills required to succeed. There were a few little girls I normally tumbled with who were truly spindly, but they were barely on my radar because their lack of muscle tone meant they struggled to execute the moves. They were just as “klutzy,” according to my mother, as the “chunky kids.” Jane, on the other hand, was pure, lean grace. (The fact that her mother could obviously center-part and otherwise get a comb through her straight hair was only more evidence of my inferiority.) For the first time, I felt uncomfortable in my royal blue leotard. It was too thick, too itchy, and now that I had officially grown into it, a bit faded in spots. Less blue than blue.

Jane’s back was to me. Though I still could not see myself in the mirror, I could see her clearly in her entirety. And now Mr. Kelley faced her, softening his tone.

“How old are you, Jane?”

“Six,” she declared with pride and a hint of lisp. Her smile revealed the most delicate and pristine empty pink gums where her grown-up teeth had yet to emerge. Jane was only 6.

Next, Mr. Kelley turned to me. “And you?” He did not ask my name. “How old are you?”

I told him.

He repeated, “Seven? Seven! Well. You’re certainly not too young. Our Jane here is only 6.”

Our Jane. So she was his Jane, everyone’s Jane, clearly beloved. I was no one’s anyone. I glanced around at the other members of the class who were either amused or uninterested, focused on their own images in the mirror, perfecting a position or move. Nowhere to be found was a friend, a kindly older face who might have offered me comfort, understanding, reassurance that I, too, was — if not impressive — at least still cute. There was no one. Even my mother had retreated from the doorway, having likely found someone to chat with.

Mr. Kelley beckoned to Jane at this point, one hand extended. I cannot recall what acrobatic maneuver he asked her to perform, what enchaînement of dance steps, but whatever it was, she executed it to the resounding admiration of the older dancers and the approval of Mr. Kelley himself. There was applause, at the height of which Jane curtsied.

I was grateful to be forgotten, but humiliation had swallowed my spirit. I was nothing compared to Jane — not talented, not cute, not clever, not anything I’d been led, by doting parents and Y-level dance and gymnastics teachers, to believe that I was. As I hung my head, my eyes took in the expanse of royal blue stretched across my midsection. The once-roomy leotard was now form-fitting, as it was perhaps meant to be, but now it shamed me too, broadcasting that this 7-year-old body was now larger than it had been when I was only 6, like Jane. And though I could not see myself in full, my image once again blocked by grown-up dancer bodies, the bulk of my self was suddenly too much to manage. My body felt messy, sloppy, like the free-form hair my mother had wrestled that morning into a single bobble-ended ponytail holder. How had Mom not known I’d have to present my unruly form and tangled puff of hair alongside Jane’s lean build and sleek princess topknots?

I held my position as the class continued. As much as I longed to leave, I would not risk attracting the maestro’s sharp eye again. Instead, I remained as still and invisible as I could. I clung to the barre, my sole ally, and settled in to watch.

There was much to observe from my post: seasoned dancers performing complex enchaînements that flowed into gymnastics moves and exquisite poses. Despite my predicament, I still loved it all. My muscles ached to join in, to dance with the cohort, an equal partner to Jane, showing Mr. Kelley that I could do it.

And here came a new combination, with balancés — waltz steps I had recently learned and was good at, that I practiced all over the living room when my father played Delibes and Prokofiev. Next was a soutenu — a spin with both feet in fifth position. No problem. I could do one of those. And now, a few other steps I was pretty sure I could pull off — if only I could release the barre and try. Did I dare? One hand at a time, I relinquished my station and ventured a few inches from its safety.

Steadying my breath, I made an attempt: a set of balancés, a soutenu, a lunge — was that right? It was! — with a grand port de bras, close fifth, coupé, glissade, jeté and on to the rest. I practiced as each group performed the steps in turn, hope awakening my limbs. I cheered myself on. I was doing it! Dancing! Coming back to myself, thinking now the other dancers would see me. Mr. Kelley himself would recognize his mistake. I was no shameful, late-arriving dud. I could dance like Jane! I was worthy. I readied myself for a chance to prove it.

But then it was done. The music stopped and Mr. Kelley took to the center, facing the mirror to demonstrate something new. I had missed my chance and now, as the other dancers crowded around, marking the new steps — unfamiliar ones that were out of my range — my chest collapsed. The maestro turned to face us, one hand raised, calling for stillness. Anyone who was already practicing stopped and came to attention. As Mr. Kelley selected an adult female dancer as a new model, explaining what to focus on, where to keep tension in the body, where to stretch, to keep weight off the heels and onto the toes, the class formed a collective pack, backing up to make space. Everyone’s eyes were on the maestro and his subject. No one looked behind them to avoid a collision or stepping on anyone else’s turned-out toes. I was once again backed against the barre.

When the first group took its turn, the other class members spread out further to observe, their backs a wall through which I could see little. During my brief attempt to join the class, I had lost track of Jane. But now, of all the backs of all the other dancers in the room, it was Jane’s which loomed before me. As she retreated from the dancing space, her dorsal view closed in: long neck, center part, blinding white leotard.

My eyes had access to just a small glint of mirror. Amid the dancing and standing bodies, I was not there at all. Where I should have been, there was only princess-fair, feather-light Jane, tall and prim, white and gold. She stood squarely in front of me, blotting me out. Was it deliberate? Did she know I was there? Could she feel my breath? Despite having no face, no body in that moment, I weighed a thousand pounds. My leotard, ill-fitting, and dowdy like burlap, felt far from royal.

I remember nothing of the class after this moment of erasure by a 6-year-old blonde girl with no front teeth. Afterward, there was the blur of the changing room, my mother helping me find the things she’d neatly folded that had since been pushed off a shelf in favor of someone’s pointe shoe bag. As we donned coats and headed for the exit, my mother, likely topping off an earlier chat, bid a pleasant goodbye to her only contemporary in the place — a thickset, matronly white woman with short blonde hair. This turned out to be none other than Jane’s mother, about whom my mother would gossip as we awaited the bus.

“Hoo-wee, was she awful!” Mom punctuated this with a whistle, correcting my assumption that their mom-to-mom chitchat indicated affinity. “That poor kid of hers.”

I raised my eyebrows. Jane? A poor kid? The bus showed up before Mom could elaborate. She handed me our fare to drop in the slot, but not even the cheery clink of coins appeased me. Once we were seated, my mother launched a decisive takedown of Jane and her mother.

“That child is her mother’s full-time job.” Mom explained that Jane’s mother was her manager. “That woman does nothing but bring her kid to dance, singing and gymnastics lessons, auditions, photo shoots and performances.” Jane didn’t go to actual school, it turned out, but was tutored by her mother. She performed in various shows, including with the Metropolitan Opera. “She works six days a week!” Though what Mom was describing didn’t sound like work. It sounded like heaven to me, and made Jane seem even more special. I asked if I could do it too.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Mom said. “You don’t want any such thing.”

Oh, but I did right then. How I did! To be the one in the white leotard with puffy sleeves and two princess buns atop my head, center stage, with all adoring eyes on me? Why, I thought, that would suit me quite well.

“You wouldn’t have time to play and do all the terrific things you do,” Mom said. “You think that Jane girl writes stories? You think Jane has friends like Robin and Lynn? Not a chance.”

I was the sort of only child whose friends were lifeblood. When other kids weren’t around, I wrote stories with characters who were imaginary friends, most of whom had multiple siblings and grandparents to boot. I shifted on the hard green plastic bus seating, leaning against Mom. After pondering whether my best friend, Robin, could become a professional kid along with me, whether I could be a professional kid who also wrote stories, I pivoted and told my mother I thought Jane was prettier than me.

Mom spat out “Ha!” inducing other riders to turn and stare. She lowered her voice but had piqued enough interest that our fellow travelers leaned in to hear where she was going. Which was to emphasize that Jane was not pretty, was in fact quite homely, about as homely as a kid could get. Not only was Jane homely, Mom asserted, she was obviously limited, deprived of a real childhood by her stage mother! I remained somber. Even at 7, I recognized such hyperbole as my mother’s go-to when I put myself down. I was already questioning her praise of me.

Mom shifted gears then, attempting instead to distract me with the news that we were having company that night: the family friends I loved most, who would be bringing at least two of their four teenage daughters. Bit by bit, I allowed myself to be cheered by Mom’s patter, by the sights of the city I loved through the dust-streaked windows of the bus: men pushing Sabrett carts with hot pretzels for sale, the fountain at Columbus Circle heralding the splendor of Central Park, the elegant high-rise apartment buildings on its western border.

Once home, I was sent straight to the tub to remove what my father referred to as the “funk” of the dance studio. Into the hamper went my royal blue leotard. I turned my back on the once-beloved garment, understanding that I would never wear it again.

Lisa Williamson Rosenberg is an author and psychotherapist. A Pushcart Prize nominee, Lisa’s short fiction has appeared in Literary Mama and The Piltdown Review, her essays in Literary Hub, Longreads, Narratively, The Common, and Mamalode. She has written two novels, Embers on the Wind and Mirror Me, both released by Little A Books.

Sara Maese is an illustrator, surface pattern designer and GIF animator from the south of Spain.

I had the biggest smile on my face while reading this. Such a comforting and lively read!

Congratulations, Lisa -- and thank you for sharing this beautiful story with the world.