Her Best Friend Was Her Secret Stalker

A 19-year-old student was inundated with lewd messages and fake Facebook profiles pretending to be her. The most shocking part was the person behind it all.

Editor's note: This article contains descriptions of rape threats.

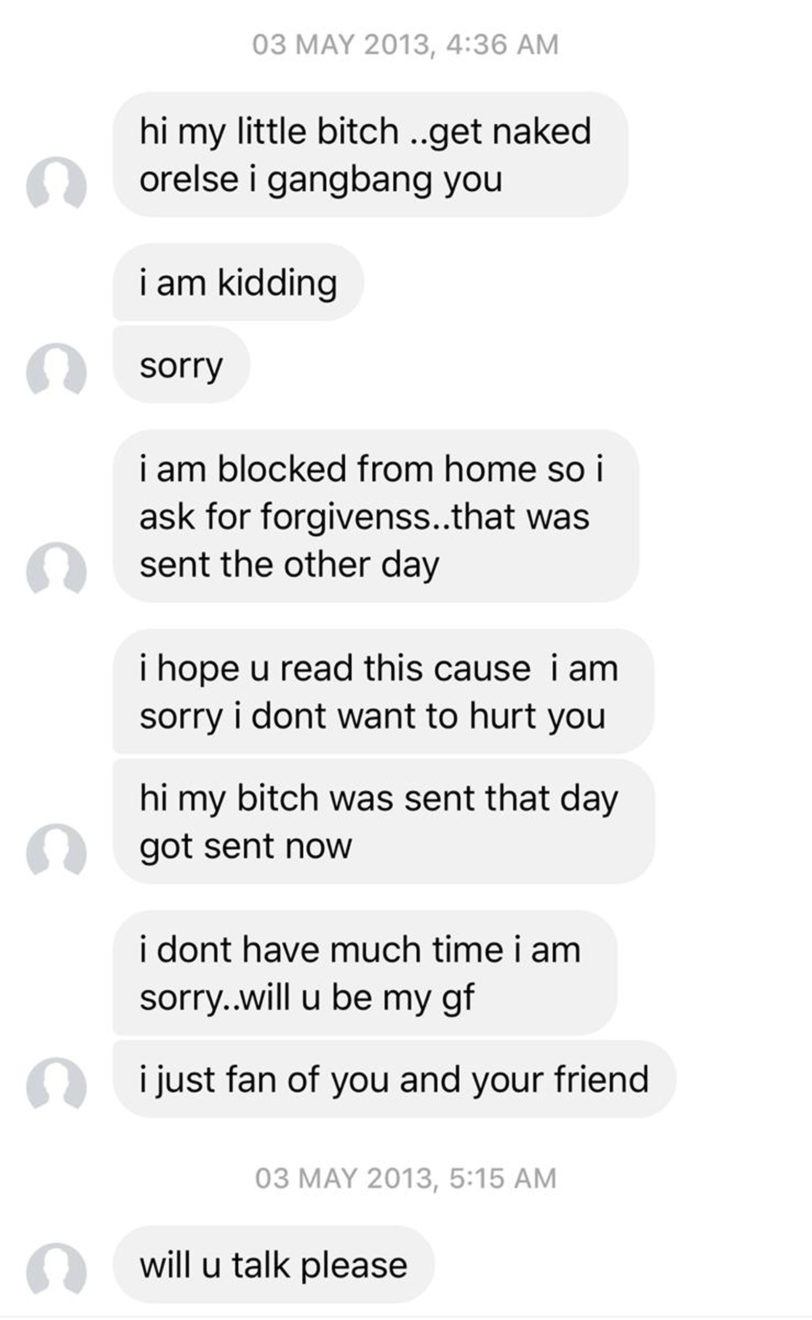

“hi my little bitch ..get naked orelse I gangbang you.”

It’s 4:36 a.m. and 19-year-old Utsa Chatterjee’s screen is glowing from a private message she’s just received on Facebook. Even though it’s early in the morning and Utsa is barely awake, she is not surprised. In recent weeks, multiple online accounts have been harassing her with lewd messages soliciting sex — sometimes as a request, sometimes more violently.

It all began when Utsa suddenly started noticing copycats of her own profile cropping up on Facebook. Accounts with the name “Utsa Chatterjee” would appear and request to add her as a friend. The fake profiles had pictures from her own account, so they were hard to distinguish from her real one. At the time, Utsa was still in high school in Bangalore, a major city in the southern part of India. With long dark hair and a pretty smile, she modeled on and off for small brands and had an active social media presence. She had a large group of friends, and when any of them pointed out the copycats, she’d ask them to report the fake accounts.

“There was a time when I kept saying, ‘Please report, please report.’ And then people would report it, and Facebook would take down the profile,” says Utsa. But that was just a temporary fix. Inevitably, “this would happen again.”

Sometimes, the mimic profiles would start conversations with Utsa. In the conversation that starts with “hi my little bitch,” on May 3, 2013, the profile follows up with, “I am kidding[,] sorry,” before sending her a spate of other messages, all poorly written, riddled with bad spelling and grammar. The person on the other end of the profile sounds desperate and pleading, eventually writing, “[I] am sorry … will you be my gf?” After several more messages, the person behind the fake profile asks “will u talk please?” before apparently giving up and signing off for a few hours.

At first, it seemed to Utsa like this was merely an annoyance, but it quickly escalated to more personal — and unsettling — attacks.

On the way home from a family getaway to a nearby resort, Utsa notices that another rogue profile has appeared.

“There was a picture of me and my dad in water in a swimming pool at the resort,” Utsa recalls. “My dad is behind me in the water not wearing a shirt, and I am in a swimsuit. It’s a cute picture of me and my father — but there was a caption that said, ‘f****d this man last night.’ And I was like, ‘Shit, that’s my father.’”

Suddenly, the fake profiles feel a lot more sinister.

Utsa begins talking about the situation with one of her closest high school friends, Debayan. Debayan is tall and reserved, with a mess of dark hair. In a photo on Utsa’s Facebook page, he is dressed in traditional Indian clothes for an event, over jeans and sandals, one arm around her and smiling awkwardly for the camera.

Debayan is a family friend; their families are part of the same Bengali community in Bangalore. Although they go to different schools, they are often around each other’s houses; they talk on the phone and see each other regularly at community events. They’ve known each other for a long time.

“He was my best friend,” Utsa recalls seven years later.

He is also known to be good with computers. “Debayan would call me up, and he would chat to me and say, ‘What’s up?’” Utsa recalls. “And I would say, ‘There is this person who is talking to me again and it’s so creepy.’

“He would say, ‘Let me see what I can do. I’ll take down the profile for you … ’”

Like her other friends, Debayan tells Utsa that he is reporting the profiles on her behalf. He often has long conversations with her, asking what the fake profiles are saying and offering to talk to them in an effort to intimidate whoever is behind them.

At one point, Utsa messages a fake account and threatens to report whoever is behind it to the cyber police. She sends the messages to Debayan in another chat. “Tell him he can get arrested,” Debayan responds.

While the accounts appear and disappear, Utsa perseveres at school. She sits for national exams and gets excellent grades. She has a choice of colleges to attend, including institutes in Delhi and Mumbai, India’s biggest metropolitan cities. But she decides on the Institute of Hotel Management in Bangalore, her top choice, since it gives her the ability to live at home and be close to her parents. In her incoming class of more than 200 students, less than half are women, and very few are from Bangalore.

College gives Utsa a newfound freedom and chance to meet new people. She begins to drift away from Debayan and her old friends. She is beginning to enjoy college life and develops a mutual crush on a boy in her class. Then one day, while standing outside of her college, a senior student approaches her, puts his arm around her shoulder and says suggestively, “Tonight, we’re going out.”

Utsa is taken aback. She has never spoken to this student before, and she has no idea what he is talking about.

It turns out the senior is equally confused. He insists that she had been sending him explicit texts all night. He’s angry that she would flirt with him in private and then ignore him in public. Utsa remains bewildered, so he pulls out his phone and shows her. “There were full-on nudes and chats and everything,” she says.

“That’s not my profile,” she insists. “It’s just my name, but that’s not me.”

When the boy doesn’t back off, her crush’s brother (also a student at the same college), steps in, telling the boy that there has obviously been a mistake. It takes some convincing, but the senior eventually leaves her alone. It’s both personally humiliating and extremely public. “This was out in college, in front of everyone,” Utsa remembers.

Then it happens several more times with different men.

The attention is frightening and unwanted, and it repeatedly leaves Utsa in tears, as she begins to fear that she might actually be assaulted. “I felt so bad. I was disgusted,” she recalls.

Utsa now realizes that the person behind the fake profiles is more dangerous than she had initially thought. At this point, the abuse has been going on for close to 18 months, and it is becoming more threatening and invasive.

But she still has no idea who could be doing this.

A few months later, Utsa is talking to her friend Sanjana when a passing comment makes her stop in her tracks. Sanjana mentions that Debayan once made a fake profile of her. She never had a Facebook profile of her own, Sanjana explains, and then one day, shortly after meeting Debayan, she suddenly had one.

Utsa is angry and confused. “That was my 2+2 moment,” she says. She starts looking for signs that Debayan could be behind the fake profiles and the harassment.

She notices that every time the abuse gets particularly bad, Debayan calls up shortly afterward to check in on her. If Utsa doesn’t mention the fake profiles or how stressed she is about them, Debayan gets more inquisitive, pushing her to disclose that the profiles had, in fact, started again.

“He would say, ‘Are you talking with someone, or chatting with someone?’ So I had these hints. He was trying to make me feel, I think, like he either knew me really well, [or] that he knew something was happening in my life.”

One day, a new picture appears on one of the fake profiles. It shows Utsa lying on her bed. Although it’s the first time she has seen the photo, Utsa immediately knows when it was taken. Debayan had been at her house a few days earlier, and he was the only person who could have taken it.

She finally decides to turn to her parents for help. She tells her mother about her growing suspicions that Debayan is behind the fake profiles and the messages to seniors at her college. Utsa’s mother doesn’t believe it at first — she’s known Debayan for a long time and is fond of him. But Utsa is fairly certain by this point, and she wants her mother to take action.

Utsa’s mother texts Debayan herself. She tells him that she and Utsa are planning to go to the cyber police to report the abuse, and she asks if Debayan wants to come with them. Debayan tries desperately via text to convince her not to do this. Initially, he invents an elaborate lie, saying that if they found out the IP address they’d trace it back to his computer, but he blames it on a friend who had visited his home. Utsa’s mother texts back that she is still going to go to the police. Debayan pleads with her again not to.

At the end of the night, after several hours of texting back and forth, Debayan gives up and confesses. He panics and texts back, “I’m going to commit suicide, it’s me who did it.” Utsa’s mother calls Debayan’s mother to tell her what her son has done.

The next day, Debayan’s parents come over to talk with Utsa’s parents. At first, Debayan’s parents try to level with Utsa’s parents, insisting that it was a mistake and that Debayan didn't mean any real harm. “They thought it was a joke. They didn’t understand how serious it was,” says Utsa.

Utsa knows that they won’t take it seriously until they see the messages themselves. “I got my laptop out and showed the messages to his dad. I made him read the offensive messages.” It’s uncomfortable, but it drives home the point. “This is not a mistake,” she says. “This is not acceptable.”

Debayan’s parents then begin to worry about the very real possibility of him going to prison. They ask Utsa what she would like in exchange for not going to the police. “His parents begged us not to let him go to jail,” Utsa says.

In India, a wide array of gender-based violence is a reality for many women, and slowly, attempts at reform are catching up with offenders. In May 2020, police in Delhi arrested a 15-year-old boy in connection with an Instagram group chat called “bois locker room” in which boys were sharing sexual content of classmates, lewd comments, and sexual assault and rape jokes. It’s a pattern indicative of growing concerns over women’s safety in India.

Ultimately, Utsa and her family agree not to press charges against Debayan, but they insist that he make a statement. “As a compromise, we made him apologize publicly on Facebook,” she says.

In a statement posted on his Facebook page, Debayan confesses and apologizes:

“Having realised the mistake i have done and its consequence and avoid cyber crime i am responsible for the fake accounts of Utsa Chatterjee..i apologize for circulating her pics and unethical messages and she is no way a person i portrayed her to be..i am sorry utsa.”

Shortly after the confession, Utsa finds out through a mutual friend that Debayan has had a girlfriend the entire time. She speaks to the girlfriend and tells her about Debayan’s actions, but the girlfriend refuses to believe Utsa, claiming that Utsa is jealous.

Utsa blocks Debayan on Facebook, and they are careful to avoid each other. Once, during an annual community celebration for the Durga Puja festival, Utsa arrives at the event and catches sight of Debayan. The sight of him reminds her of the steady abuse, and she says, “I don’t know if I can do this,” before turning back home and missing the event.

In the years since, Utsa has finished her degree and moved overseas to complete a master’s degree in New Zealand. Debayan declined requests to speak on the record regarding the incidents described in this article.

When reading the messages now, Utsa chides herself for her naïveté. It seems obvious to her that there were signs all along — signs she didn’t see at the time. “Looking back on it, he always liked me, and I was like, ‘We’re friends.’ I dated other people, and he didn’t like it. He would be annoyed that I was dating other people.” She says that Debayan is an only son — finally born after six years of prayers by his parents — and that he was used to getting what he wanted.

She theorizes that her former best friend started the abuse so that he could prove that he could help her through it by making the accounts go away and “saving her” from the attacks. “He tried to be my knight in shining armor and rescue me from all these people,” she says.

The fake profiles have since been deleted. The final screenshot she shares is from Debayan’s own now-abandoned Facebook profile. It reads:

I feel disgusted for loosing you, you meant alot to me and i myself don’t know why I did those disgusting things.

But that wasn’t the end of it for Utsa.

“All this happened, and [then] the gossip started,” she says. Despite Debayan’s confessions, rumors that Utsa had invented the abuse for attention were quick to follow. Victim-blaming is common in India, and such rumors can be particularly nasty for women. “The blame often ends up on the girl,” Utsa says.

There was also fallout within their local Bengali community. “My parents stopped getting invited to parties and [were] being left out of the community. I used to think this was my fault,” says Utsa. Debayan’s parents had lived in Bangalore much longer and had known many in the community since they’d been children themselves. Utsa’s parents had only moved to the city a few years earlier.

“It became a very bitter thing,” says Utsa. “Who do you blame? The guy you’ve known for years or this new guy who has just come in? Debayan’s parents had known the Bengali community in Bangalore from when they were born. My parents were the newcomers.” Ultimately, Utsa’s parents stopped attending events if they knew that Debayan’s family was going to be there.

The abuse has changed other things for Utsa too, making it difficult for her to let people in like she did when she was younger. “I feel like it’s left such a scar. I don’t feel like I can trust people the way I used to,” she says.

But she is careful to highlight how lucky she was to have a mother who believed her. She is always deeply affected when she hears about other teenagers who have committed suicide over online abuse. Even now, nearly seven years after Debayan’s confession, occasionally someone will get in touch to tell her that a similar thing has happened to them. She always urges them to talk to someone about it. “I was really glad I could speak to my mum,” says Utsa. She emphasizes that having that kind of help is part of the reason she continues to tell her story. “I think that’s really important,” she says. And if someone who is going through a similar experience reads this article, Utsa says that she hopes, above all, that the person “realizes that they can speak to someone.”

Amira Aleem is a writer based between London (where her heart is) and Copenhagen (where her job is). She grew up in India and is interested in stories on global development, human rights and the subcontinent.

Kaylynn Kim is a cartoonist and illustrator from Los Angeles.

Farahnaz Mohammed (you can call her Farah) is a nomadic journalist, based wherever there’s an internet connection.