I Was a Hard-Nosed Amateur Boxer. Now I’m a Buddhist Monk.

How finding my footing in the ring led me down the path to Zen.

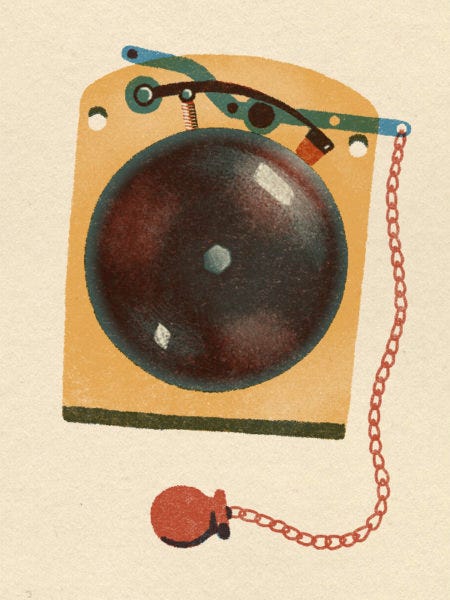

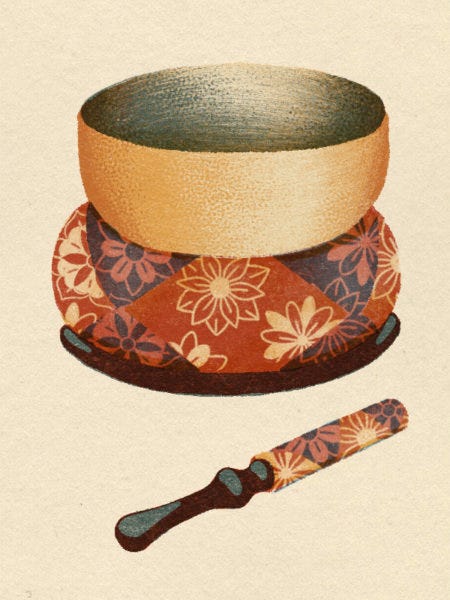

This morning, in Portland, Oregon, I sat in half-lotus position in front of my altar. As usual, I was wearing Japanese monastic attire, and had a Buddhist rosary wound around my left wrist. I looked at the statue of Bodhidharma, founder of Zen, and at the photograph of my late teacher. The bell rang, beginning my meditation. I’ve heard it ring thousands of times in the two decades that I’ve been a Zen Buddhist monk. As usual, I bowed, then sat with a clear mind. I was no longer alone.

More than thirty years ago, in Glasgow, Scotland, a different bell rang, but it had a similarly profound impact on my life.

I was seventeen, and I had gone to a boxing gym for the first time. I didn’t talk to anyone in the changing room as I got ready, or when the training began. I jumped rope. I punched the heavy bag. I did floor exercises. Then the coach called out, “Get gloved up, boys.” It was time for sparring.

There was a cupboard that contained a dozen pairs of sparring gloves, with heavier padding than the gloves used in competition. Along with the other young men, I went to the cupboard, got a pair, and clumsily put them on.

I was staring at the untied laces, and considering pulling off both gloves and fleeing the gym, when a boxer standing nearby, whose hands were still bare, casually took me by the arm and laced me up. As the coach called me to the ring to spar, there were tears in my eyes. He thought I was nervous about getting hit. I wasn’t at all.

At the time, I was so alienated that I had no idea people helped each other. I had never received, or given, any kindness. The only social currencies I had any experience of were violence and coercion. I had been raped and beaten and I had gone hungry and, except for when I had been used, or been told that I was worthless and stupid, I had been ignored. That a person I didn’t know would help me put on a boxing glove, for no other reason than that I was a fellow boxer who needed help, was overwhelming to me. As my spar-mate and I squared off, I had never felt less violent.

That night, I left the gym by myself, but, for the first time ever, I wasn’t alone. The laughter, the camaraderie, the sense of community, came with me. I returned the next training night, and every other one. I didn’t learn how to fight in that gym. I had been fighting for a long time, and the training only sharpened my skills. I learned about friendship. In a place of intense, focused violence, I learned about compassion.

It wasn’t long until the coach scheduled my first fight. My opponent glowered at me as we touched gloves in another ring, in the center of a smoky little nightclub. I felt nothing toward him, no hostility, no antagonism. I went back to my corner. My coach put in my mouthpiece, and the bell rang.

I was five-eleven, and weighed 118 pounds, a pale stick made of muscle and bone. My opponent was several inches shorter, much wider, and this was not his first fight. As I climbed into the ring and my coach removed my robe, I said a nervous prayer that neither I nor my opponent would be seriously injured. As I looked at the spectators, I was aware of two things: That most of those watching expected my opponent to beat me easily and quickly, and that I didn’t care what any of them thought. It wasn't about them, or about my opponent, or about me. It was about the fight.

The guy was much stronger than me. After two minutes, when the first round ended, I had a welt under my left eye. As I sat on the stool, my coach told me that I had lost the round. I knew, and I didn’t care.

As the second round began, some of the spectators yelled for my opponent to finish it, walk through me, knock me out. A few others yelled encouragement to me.

My opponent became angry when I smiled at him as we circled each other. I didn’t care how he felt. I slipped his jab and countered with one of my own, then did it again, and then again. As he tried to force me to back up, I hooked off the jab, hard, and he walked into it. I saw the shock on his face as he tried to keep his legs under him.

I had never felt so peaceful, because there was no sense of “I.” Only “this,” the thing I was doing in that moment.

After the fight, which I won by a points decision, my coach told me how happy he was for me. I ate a chicken leg and drank a can of soda, and my coach gave me a ride home. A few blocks from where I lived, I asked him to let me out because I wanted to walk the rest of the way. We shook hands, and I got out of his car, and he saluted as he drove off.

It was cold, and I saw nobody else on the street except a cop. I felt a happiness, without passion, that I had never known before. I did not expect to be able to fall asleep easily, but I was wrong. I slept well, and woke early.

It was a taste of the peace I would later find through Zen. “If you practice here you’re responsible for yourself,” the elderly priest, whose hands shook with Parkinson’s, told me on my first visit to the Zen center he ran. “You’ll never be any better than you are now. Anything you have to deal with now, you’ll have to deal with for the rest of your life.”

“So why should I bother with Zen?”

“I don’t know. I never said you should. You came here.”

When I look at these words, they seem harsh, uncaring. They were anything but. Hearing them, I felt an almost overwhelming sense of relief. I knew I was being leveled with. I wasn’t being lied to, and so, even though I couldn’t understand why anyone would practice Zen if it wasn’t going to “help” them, I trusted it and I trusted the priest. When the other two participants that evening showed up, I joined in the service. We sat on cushions, chanted in Japanese, and then spent two half-hour periods in silent, objectless meditation called zazen, broken up by ten minutes of walking meditation, clockwise around the room, called kinhin.

When the priest told me just to sit still, I asked him what to do with my mind. He told me I didn’t have to do anything with it, but to just observe it, be present, and, whenever I realized that I wasn’t, to just to come back to where I was.

I thought it was the stupidest, most pointless thing ever – and I knew it was going to save my life. I don’t know how I knew, but I had never felt so certain. And I was right. My sad fury, which I had feared would eventually lead me to prison or the morgue, did not diminish with practice – but it lost all power over me. I would come to relate to my anger in the same way that I related to the anger of other people – as something I was aware of, but that was irrelevant to me.

A couple years later, I took the vows of a Zen monk, a commitment to serve all sentient beings, to save them from suffering, understanding that this includes myself, but without concern for personal salvation. My sangha, or Buddhist group, is not affiliated with any mainstream Zen schools, but, for me, being a monk isn't about jumping through institutional hoops — it's about living by my vow. I vowed to meet life as it is, rather than attaching to my preferences about how it should be, to meet myself and others as we are, rather than attaching to my preferences about how we should be. The essence of the vows are contained in the words that I chant every day, at the end of my meditation:

Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to save them.

Delusions are inexhaustible; I vow to end them.

The Dharmas are boundless; I vow to master them.

The Buddha Way is unsurpassable; I vow to attain it.

What I had experienced in boxing is what Zen Buddhists call single-pointed attention, a state of such presence with the activity of the moment, with the moment as it is, that there is no room for ego, for any consideration of self. It’s a peace and freedom that can only be found in compassionate detachment. When I had reached this state through boxing, I’d left it behind as soon as I stepped out of the ring. It was the same with zazen for a while. But, so gradually that I didn’t notice, what I found meditating started to come with me when I stood up and left. And, after a while, I stopped finding it on the cushion but instead brought it there with me, hands palm-to-palm, meeting the moment, sitting present with all creation, and all destruction, each time the bell rang.

Dogo Barry Graham is a novelist, journalist, poet and Zen Buddhist monk.

Arlin Ortiz is an artist working in Los Angeles, California.