Longshot Dreams and Slapshot Fiends in the Ultimate ’90s Pro Sports League

In the age when Rollerblades were king, a crew of wide-eyed rookies and grizzled NHL vets brought hockey-on-wheels to the cusp of the big time.

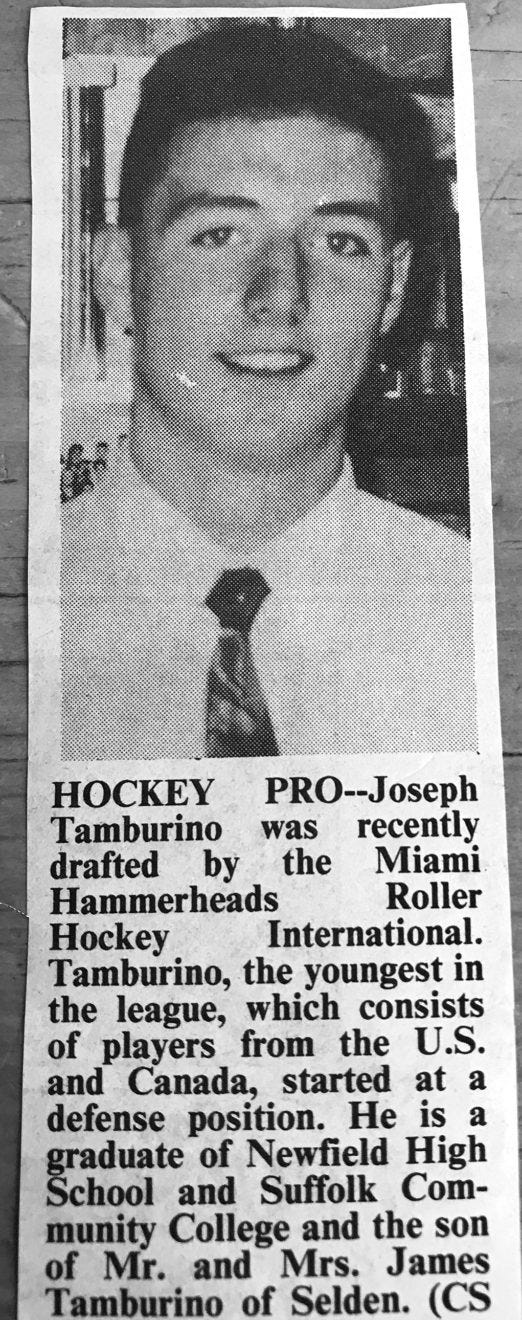

Joe Tamburino was a longshot. Describing his path to becoming a professional hockey player any other way would be an understatement.

He fell in love with the sport while watching the New York Islanders dynasty of the early 1980s. But for a blue-collar kid like Joe, ice hockey was never really an option — back then, rinks were scarce, and ice time was expensive. To emulate his favorite players — Pat LaFontaine, Bobby Nystrom and Mike Bossy — Joe took to the streets of Long Island on his quad skates, and later, inline blades.

As a teenager, Joe realized he was a pretty gifted player. Guys from the neighborhood would often ask him to fill in on their teams, picking him up and dropping him off, as he hadn’t yet gotten a driver’s license. When Joe was 16, he started playing in a full-contact roller league in Queens, widely recognized as the best in New York City. A few years later, when the brand-new Roller Hockey International professional league was formed, Joe’s standout play against some of New York’s top players gave him the confidence to go out for the league’s open tryouts.

Despite his talent, Joe was a 19-year-old with barely any ice experience — just a short stint in junior hockey plus his high school team. Here he was, competing head-to-head against guys who played professional or collegiate ice hockey. Even his parents, though they were extremely supportive, expected him home sooner rather than later.

Joe spent the months leading up to the tryout training outside of his Long Island home while his 12-year-old brother, Jimmy, skated alongside him. The brothers were inseparable, despite their seven-year age difference, and Joe quickly recognized his brother had an equal (if not greater) passion for the game. The boys would spend hours out in front of their house — Joe in an Islanders jersey and Jimmy in a Rangers sweater — pretending they were battling for the Stanley Cup.

Despite the long odds, after tryouts Joe somehow found himself with an invitation to training camp with the Florida Hammerheads, one of 12 teams participating in the newly founded league. When they broke for the season, Joe had a professional contract.

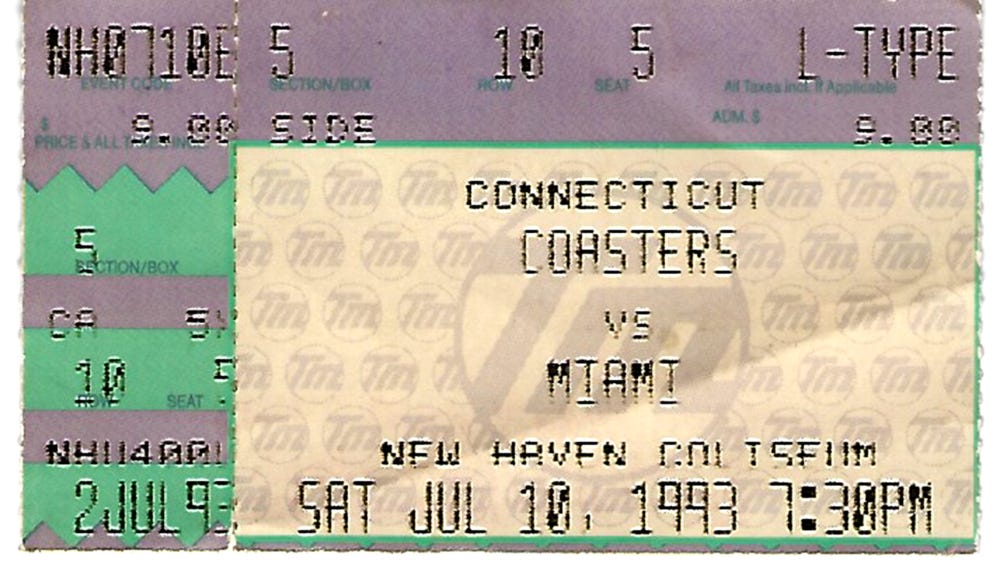

“I couldn’t wait to get out on the rink, just for warm-ups, just to be in that jersey and for my family and friends just to see that,” Joe said of his professional debut in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1993, the passion radiating through his Long Island accent. His thick, dark brown hair has thinned and grayed a bit in the years since, but Joe, now 46, still possesses a warm, youthful grin and an athletic build — he hasn’t completely ruled out returning to competitive play one day.

But before young Joe laced up his skates, there was something he had to do.

He showed up to his family’s hotel room carrying a hockey bag stuffed with equipment — skates, wheels, tape, stick blades and a head-to-toe set of team gear. It wasn’t for him. It was a surprise for Jimmy.

“I was always thinking of him,” Joe said. “And I’m like, ‘I gotta take care of my little brother while I’m having this experience.’”

And as Joe played the role of Santa Claus on Christmas morning, he had one more surprise to dish out after the bag was emptied. He was taking Jimmy to the Hammerheads’ morning skate.

“Well, pack it up,” Joe told his brother. “We’re going to the stadium.”

Jimmy, reflecting on the moment recently, nearly three decades later, described the experience in one word: “incredible.”

It was kids like Joe and Jimmy Tamburino who originally caught the eye of a trailblazing sports entrepreneur in 1991 and inspired him to dream up the idea of professional roller hockey.

Dennis Murphy was no stranger to bold ideas. In the early 1990s, Murphy had already built his reputation by founding the American Basketball Association (ABA), World Hockey Association (WHA) and World Team Tennis (WTT), introducing innovations such as the three-point line and slam-dunk contest in basketball, and the first $1 million contract in hockey. So, when he drove by a group of kids playing roller hockey in the streets of Los Angeles — just as the Tamburino brothers were doing on the other side of the country — he came up with an idea.

Murphy sat and watched for half an hour, the wheels turning in his head. No ice. No rink. No fancy equipment. Yet, the kids’ passion and enthusiasm captured his imagination. Could this be developed into a professional league?

Across the country, the inline skating craze was taking hold. Thanks to the Los Angeles Kings’ acquisition of Wayne Gretzky in 1988 and the advent of the Rollerblade earlier the same decade, roller hockey’s popularity was booming.

“What do you think of that?” Murphy asked fellow businessmen Larry King and Alex Bellehumeur. As Murphy recalls, the pair immediately liked the idea, and the coalition behind Roller Hockey International (RHI) was born.

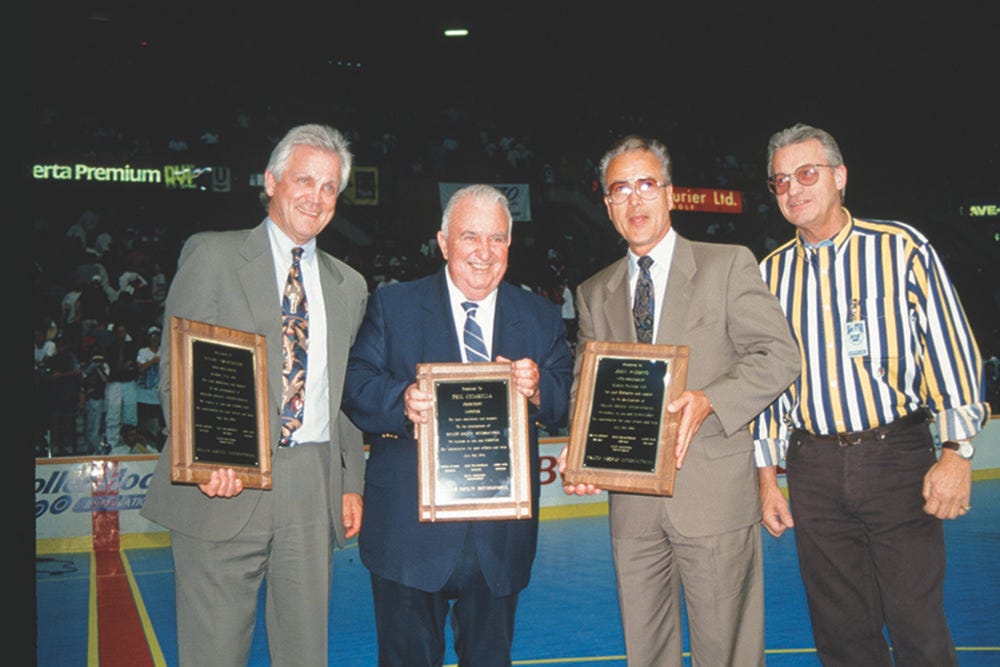

King, not to be confused with the talk show host of the same name, rose to prominence as an attorney, promoter and the ex-husband of tennis star Billie Jean King. In 1973, he co-founded WTT with Murphy. Bellehumeur had built his name in the world of real estate development. While the trio boasted an impressive amount of business firepower, Murphy still needed to add a layer of hockey legitimacy to his new league. For that, he turned to six-time Stanley Cup champion Ralph Backstrom.

Backstrom devised a set of rules for RHI that would go on to govern the many iterations of professional roller hockey to come. He removed ice hockey’s blue lines, made offsides a factor of the center red line, skated four-on-four, played four 12-minute quarters and went straight to a shootout after regulation. These changes made for a wide-open, offensive-minded and higher scoring version of hockey. “People want to see goals,” Backstrom said in Richard Graham’s Wheelers, Dealers, Pucks & Bucks: A Rocking History of Roller Hockey International. “They didn’t want to see a 1-0 roller hockey game.”

A successful four-city exhibition tour in 1992 drew thousands of fans and legitimized Murphy’s idea. RHI launched with 12 teams a year later, and expectations were high.

Among the ranks of RHI team owners was Jeanie Buss, future owner and president of the Los Angeles Lakers (at the time, her father, Dr. Jerry Buss, owned the Lakers). Teams played in NHL arenas and an ESPN TV deal brought the game to the national stage. It created opportunities for players toiling in the lower levels of ice hockey; it was a fun way to earn extra cash and stay in shape during the summer.

“Even though it’s not the NHL, you’re able to say that ‘Hey, I got to be a professional athlete,’” said Jimmy Vivona, a former RHI player.

But to many, it was so much more than that.

The rise of hockey on roller skates expanded the accessibility of the sport, bridging the gap between the NHL “and the kid whose family couldn’t afford ice hockey,” says Brandon Bywater, a childhood fan of RHI’s Dallas Stallions. RHI validated a generation of roller-only players without a platform and inspired a new one. It offered a chance for a guy like Joe Tamburino to compete at the highest level of the sport, even though he didn’t come from the typical affluent background of most ice hockey players. In short, RHI did more than offer a breakneck-speed version of summer hockey: It broke down the social barriers that walled off existing leagues, making the dream of playing professionally available to everyone.

And for Murphy, then in his 60s, RHI was to be the grand finale to an illustrious career. His excitement for the new league was boundless, according to Richard Graham, who edited Murphy’s autobiography. Even as a summer league, Murphy envisioned a bright future for the enterprise.

“At the beginning, I think Dennis was pure of heart,” Graham said. He wanted to “make this a league that could become a WHA or an ABA of roller hockey and he went for it and I love him for it.”

When Jimmy Tamburino stepped out of the concourse and into the stands of the New Haven Coliseum, he couldn’t believe his eyes. Everything looked and sounded like an NHL game. The music was blaring, and fans were starting to arrive at the 10,000-seat arena to watch the Florida Hammerheads take on the Connecticut Coasters. His dad stood right beside him, equally surprised. Both father and son couldn’t help but smile.

RHI was mainly composed of lower-level ice hockey guys in 1993, but it did have its fair share of star power. There were NHL veterans like Dan Daoust, who, after eight years and 253 points with the Toronto Maple Leafs, finished his North American hockey career with the Toronto Planets, and Garry “Iron Man” Unger, the first NHLer to play in more than 900 consecutive games, who coached the Oakland Skates. There was also player-coach-captain Perry Turnbull, a nine-year NHL veteran known for his gritty, physical play. Dave “Tiger” Williams (Vancouver Voodoo), the NHL’s all-time leader in penalty minutes, also found a second act as a coach in the new league.

Williams was a tenacious player who never lacked passion for the game and was known for his exuberant goal celebrations. Teammates and fans loved him for his fighting, and while the penalty minutes might imply that he was a dirty player, it depends who you ask. He never shied away from displaying his quick wit, famously saying “them Penguins are done like dinner” after Williams’ Maple Leafs knocked Pittsburgh out of the 1977 playoffs. For a brief moment during his RHI stint, Williams returned to action as a player for one game, picking up a goal, an assist and a pair of penalty minutes.

As a 19-year-old kid about to play his first professional game, Joe Tamburino was nervous and filled with doubt. Just play solid, own the boards and do your job, he reminded himself. But ultimately, it was a pep talk from his dad earlier that morning that quelled his nerves.

“To hell with all these guys,” his dad told him. “Give it your best. You’re just as good.”

Adrenaline surged when Joe took the floor for warm-ups, washing away any lingering apprehension. He looked up into the stands and spotted the group of roughly 60 that had driven up from Long Island to see his debut. His mother was crying tears of joy.

Jimmy couldn’t contain his excitement. At any moment, he could conjure a memory of skating with his brother in the streets of Long Island or at the local rink. Now, here was his big brother, his hero, in full pads and a teal Hammerheads sweater standing shoulder-to-shoulder with professionals.

After the Hammerheads returned to the tunnel, Jimmy ran down and secured a spot right against the railing. When the team returned for introductions, Jimmy spotted Joe in the very back of the line. The two brothers made eye contact and Joe gave his brother a wink.

Jimmy, now 39 years old, gets choked up recalling the moment.

“It was always everyone’s dream to make it to the NHL,” Jimmy said. “But looking back now and spending all that time with [Joe], it doesn’t even matter. It’s almost like this journey was better in a way. It’s hard to explain, but it’s just incredible. It taught us so much and gave us incredible experiences that a lot of people don’t get to have, and a lot of people would probably never understand how much it really meant.”

The Hammerheads lost 10-9, and although Joe didn’t score, he played nearly the entire game. The Tamburinos celebrated that night, renting a suite on the top floor of the hotel and hosting nearly 30 people, including most of the Hammerheads’ roster. The family was proud, and Joe’s dad was the center of attention, laughing, joking and beaming about his son’s accomplishment. Joe enjoyed the company but didn’t touch a drink. He had a game the next day and was still fearful of getting cut. Maybe it was a bit of an overreaction in the moment. But Joe knew the fantasy was fleeting.

The 1993 season would be the only one he spent officially on an RHI roster. He bounced around from tryout to tryout for the next few years, even chasing minor league ice hockey as well. Most of his efforts proved fruitless.

“You’re clinging on,” Joe said of his subsequent seasons. “I want to stick around. I know I can play here. I know I’m good enough. But a lot of times it didn’t work out that way.”

RHI “enjoyed its golden age” from 1994 to 1996, according to The Hockey News. Partnering with ESPN gave the fledging league access to millions of homes, and some teams boasted strong attendance numbers in the tens of thousands (mainly on the West Coast). Game 2 of the 1995 RHI Championship in Montreal, between the San Jose Rhinos and Montreal Roadrunners, reportedly drew more than 15,000 fans. RHI remains unmatched in the roller hockey world in terms of “its sheer size” and “its presence on TV,” and while the league didn’t spawn any mega stars, a few notable players and coaches did rise out of its ranks.

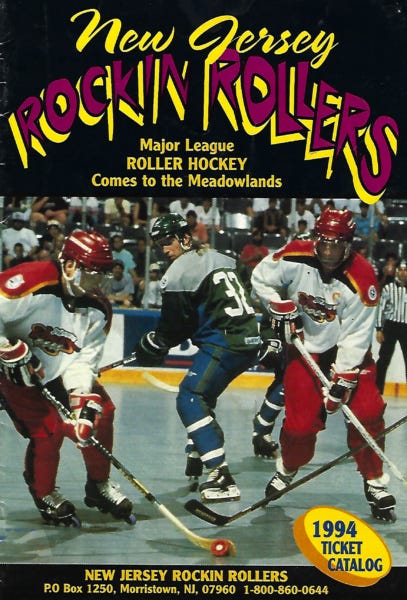

Glen Metropolit, an alumnus of the Anaheim Bullfrogs, Long Island Jawz and New Jersey Rockin’ Rollers, went on to score 159 points in eight NHL seasons. Future NHL All-Star goalie Manny Legace and coach Barry Trotz, who led the 2018 Washington Capitals to the franchise’s first Stanley Cup Championship, both had stints in RHI.

But by 1997, RHI was dying. The league expanded too quickly, says Murphy, doubling in size from 12 to 24 teams by its second season. Playing in NHL-sized venues created massive overhead for the league, and Jeffrey Buma, the self-described “unofficial right-hand man” to Murphy, cites unreliable ownership as a key factor in RHI’s demise. From its inaugural season in 1993 to its hiatus in 1998, the league had 22 teams fold. “You’re only as strong as your weakest link, so that was an issue,” Buma said.

Later on, teams started supplementing their revenues with advertising side deals, costing RHI its multimillion-dollar deal with Pepsi. Sensing the forthcoming chaos, ESPN opted out of its broadcast deal with RHI in 1997, eradicating a valuable revenue stream and leaving RHI without a national audience. The league also lost millions in a bitter patent dispute over the puck it developed for play and commercial sales. “We made some mistakes and unfortunately mistakes cost you,” Murphy said.

Five years after Joe Tamburino’s first game, money troubles forced RHI into hiatus.

That would give way to a new league, Major League Roller Hockey (MLRH), which operated on a much smaller scale.

Gone were the days of playing in NHL arenas. Teams shuffled in and out of small rinks all around the country, and the quality of the actual games suffered. Joe captained the New York Riot of MLRH, but the experience was hardly the same. Rosters all around the league were filled with goons more equipped to lay hits and start fights than score goals. There was limited success, but at its core, MLRH was a renegade, fly-by-the-seat-of-its-pants operation. The league struggled to stay organized with a skeleton staff, money woes persisted, there was a huge gap in talent between the good teams and the less-competitive ones, and the 1997 inaugural season was even erased from the record.

The end of the 1990s closed the book on roller hockey’s legitimacy as a professional sport. MLRH fell into hiatus in 1999 and returned as a shell of itself. Upstarts like the Professional Inline Hockey Association never recaptured the success of RHI, which attempted a short-lived comeback before finally ceasing operations in 2001. Now, the highest levels of pro roller hockey are tournament-based. Events such as the North American Roller Hockey Championships, the Roller Hockey Tournament Series and State Wars draw the limited sponsor money and elite talent still filtering through the game.

For Joe Tamburino, there was no hero’s welcome when he returned home years after that first pro game — no autograph signings, TV appearances or meet and greets. The collapse of the roller hockey world meant putting his dream to bed. He became a steamfitter, like his father before him, joined the union and built a life for himself on Long Island.

But Joe doesn’t see it as a failure or harbor any bitterness about his years spent in professional roller hockey.

“It’s a shame it didn’t last or go in the direction it had the potential to go, but it had a great, positive impact on me,” Joe said. “It molded me in a way.”

The results were a set of lasting memories and life lessons. Joe says that the experience taught him to overcome obstacles and be patient with the unexpected, and how to deal with stress. It also forged the bond between the Tamburino brothers, who credit RHI with laying the foundations for an enduring relationship, long after the league lights faded. “This game, to this day, has a major impact on our friendship, and he has a lot of passion for the game,” Joe said.

Jimmy chased his own career, playing junior ice hockey and college roller before hanging up his own skates. He took up coaching immediately after and fell in love with it. In the past four years, Jimmy has led Farmingdale State College to three consecutive National Collegiate Roller Hockey Association Division I National Championships and Team USA to a gold medal at the Junior Men’s Inline Hockey World Championships in Italy. Today, the brothers regularly host roller hockey clinics on Long Island. “I’ve just been hooked to the game ever since,” Jimmy said. “And Joe being a part of RHI pretty much inspired me.”

The demise of RHI proved to be the unofficial end of Murphy’s career. After the league permanently disbanded, he attempted to reboot his original idea unsuccessfully. In the decades since, Murphy has reflected on his accomplishments, participating in documentaries and books about himself, the ABA, WHA and RHI. He currently lives a quiet life in California.

Joe Tamburino, the longshot, never became a hockey star. But he did get to live his dream in a 10,000-seat stadium, with 60 of his family and friends cheering him on, as brief as it was. And for guys like him, that became the legacy of professional roller hockey. It was more than a money grab or a way for ice hockey guys to stay in shape during the summer.

There are times where Joe still goes out to skate in the streets. It reminds him of all those hours spent training for the Hammerheads with Jimmy by his side. And now that he’s a father to an 11-year-old boy, he says he feels fortunate.

“It was a big part of my life. I get to tell my little guy stories about it,” Joe said, adding that his experiences help him teach his son never to give up and to go after his dreams.

“I had no shot at making it,” Joe said. “But I made it.”

Justin Birnbaum is a New York City-based writer who covers the business of sports.

Farahnaz Mohammed (you can call her Farah) is a nomadic journalist, based wherever there’s an internet connection.