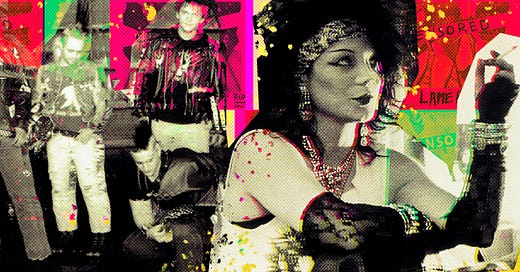

Punk Rock Freaks in the Heart of Hollywood

It was the era when video killed the radio star, when glitz and glamor and bubblegum pop dominated the airwaves. Meanwhile, a handful of musicians and misfits were subverting the pop culture narrative forever.

Iris Berry had had enough. For the second time that day, she stomped from behind the bar, across the dance floor, past rows of U-shaped red leather booths, through the haze of cigarette smoke and stale beer, over to the DJs to ask them to turn the music down. It was 1982 and Berry was a new bartender at the Cathay de Grande, a club set in the basement of a Chinese restaurant in Hollywood. Just a couple of years earlier, she had been struggling to graduate from high school in Pacoima — a San Fernando Valley town she describes as “all gangs and car clubs” at the time. Berry had gone from wearing Dittos jeans and feathered hair as a latchkey kid in the Valley to shoplifting at the nearby mall to working in a biker bar (thanks to a good fake ID), which is where she was bitten by the punk bug. Soon she was bussing over the hill to hang out in Hollywood, and by ’82 the 21-year-old raven-haired beauty was a fixture on the scene there, her hair teased high above her sea-blue eyes, porcelain cheekbones and red “cherries in the snow” Revlon lipstick.

The Cathay featured bands of all stripes all week long, and it opened early on Sundays for the Sunday Club, a daytime event hosted by DJ/promoter Bob Forrest. A bespectacled 21-year-old who moved to Los Angeles from Palm Springs, Forrest was known for carrying around armloads of books to support his reading habit, sometimes selling them to support another habit.

On one of Berry’s first days working at the club, a few drunk punks played softball in the parking lot while two others DJ’d country and metal music. Top Jimmy, a white-boy blues singer with a Kentucky drawl, ordered a whisky and beer from Berry, pulling a roll of stamps from his pocket to pay for his drink. “This was the first time I met Top Jimmy,” remembers Berry. “He told me he had broken into a stamp machine at the post office. I told my boss, ‘He doesn’t have any money.’ And he says, ‘Let him pay with stamps.’”

Later that day, another guy walked up and emptied a pocketful of pennies onto the bar to pay for his drinks. Berry was annoyed, but the guy was cute, so she acquiesced.

There was still the matter of the blaring music. “You need to lower it!” she yelled. “I can’t hear my customers.”

“Huh?” both DJs mimed, pretending they couldn’t hear because the music was too loud.

“I was getting a sore throat from trying to talk to my customers. So finally I go up to the DJ booth with a pitcher of beer,” Berry recalls. Again she told them to lower the music. They laughed and this time made it louder. So, she says, “I poured the pitcher of beer all over the turntables. Smoke was coming out. They screamed. I said, ‘I told you to lower the fucking music!’ And I just walked off.”

To her surprise, Berry didn’t get fired. It was hard to get fired from the Cathay de Grande.

That night, after working a second shift, Berry went home to her punk rock group house, a fading 1920s stucco building just off Hollywood Boulevard, affectionately known as Disgraceland. She had taken the room recently vacated by singer Belinda Carlisle, whose band the Go-Go’s had recently topped the Billboard 200 charts for six weeks in a row.

The house was nicknamed for a plaster bust of Elvis that had witnessed all kinds of debauchery from its perch on the mantle — and been adorned with Alice Cooper eye makeup by Berry’s best friend and roomie, LA Weekly writer Pleasant Gehman. Flyers for punk shows plastered the walls, the house phone never stopped ringing, and a steady flow of beer and drugs kept the party going.

It was a simple time, Berry wrote decades later in her book The Daughters of Bastards: “Red lipstick, blue-black hair dye and black fishnets, that’s all I needed. Oh, and some heroin to keep the feelings down.”

When Berry got home that night, the cute guy from the bar, the one who’d paid in pennies, was passed out on their couch.

“Oh, that’s Joe Wood,” said Gehman. “He’s the new singer for T.S.O.L.” While that band, True Sounds of Liberty, might not be a household name, its members—along with the rest of the revolving cast of tenants and couch-crashers at Disgraceland—would soon change the face of popular music.

The swirl of artsy, disaffected young punks who gathered here, and at similar punk group houses like the Wilton Hilton, Riot House and the Black Hole down in Orange County, had no idea yet that the makeshift music they were playing to tiny crowds at dusty bars would influence pop culture for decades to come. Fame and fortune was on the horizon for some of them, but that was never the point. Partying, playing pranks and making music together was just fun.

Berry describes these years as a time when all of her friends were living and breathing punk rock. “You went to work, they were there. You came home, they were there. You woke up, they were there.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.