The Acrobatic Immigrant Who Invented Pilates in a Prisoner of War Camp

Interned during WWI, circus entertainer Joseph Pilates used found materials and his fellow prisoners as his test lab, and imagined an exercise system that would captivate millions.

In the early afternoon of September 12, 1915, a British vessel set off from the western coast of England and freighted up the Irish Sea toward Scotland. It was a warm day, but most of the men aboard, confined to an airless chamber below deck, longed only to escape the sickening quarters. The passage was short: After traveling 70 miles, the SS Connaught docked at the Douglas breakwater on the Isle of Man. Immediately, the British guards overseeing the ship lowered a ramp and began shouting commands. Wearily, the men disembarked.

The scene was chaotic. “There was no law or order whatsoever,” a reporter for the Peel City Guardian wrote. Within minutes, men from the ship were confused with locals milling about the harbor, most of whom were Manx people native to the isle. Eventually, separated from the crowd, they marched along the South Quay and boarded a steam-powered train that weaved sluggishly into the heart of the isle. As the tin-gray sky turned starless black, the train stopped at St. John’s station. Another march followed, this time under the watch of the King’s Liverpool Regiment. For hours, they trudged through soil that sunk like clay, over streams, through cattle gates. In the distance, hundreds of bright lights flickered, a site rare in the customary blackness of wartime. “Almost like Paris,” one of the men thought.

The beauty soon faded, for the lights illumined not a city but a compound enclosed by barbed wire. Only when the sun rose the next morning did the scene become fully apparent. Inside the fences, in front of striking turf-clad hills, the men saw dozens of closely packed, sterile huts — the bunks of Knockaloe Internment Camp.

Like the thousands already confined, the new arrivals were mostly unsuspecting professionals who had emigrated from throughout Europe to England, in search of better wages and opportunities. With the Aliens Restriction Act of 1914, the British government formally authorized the internment of anyone suspected of espionage. Having a German name was reason enough, and by 1915, around 24,000 men were placed in Knockaloe.

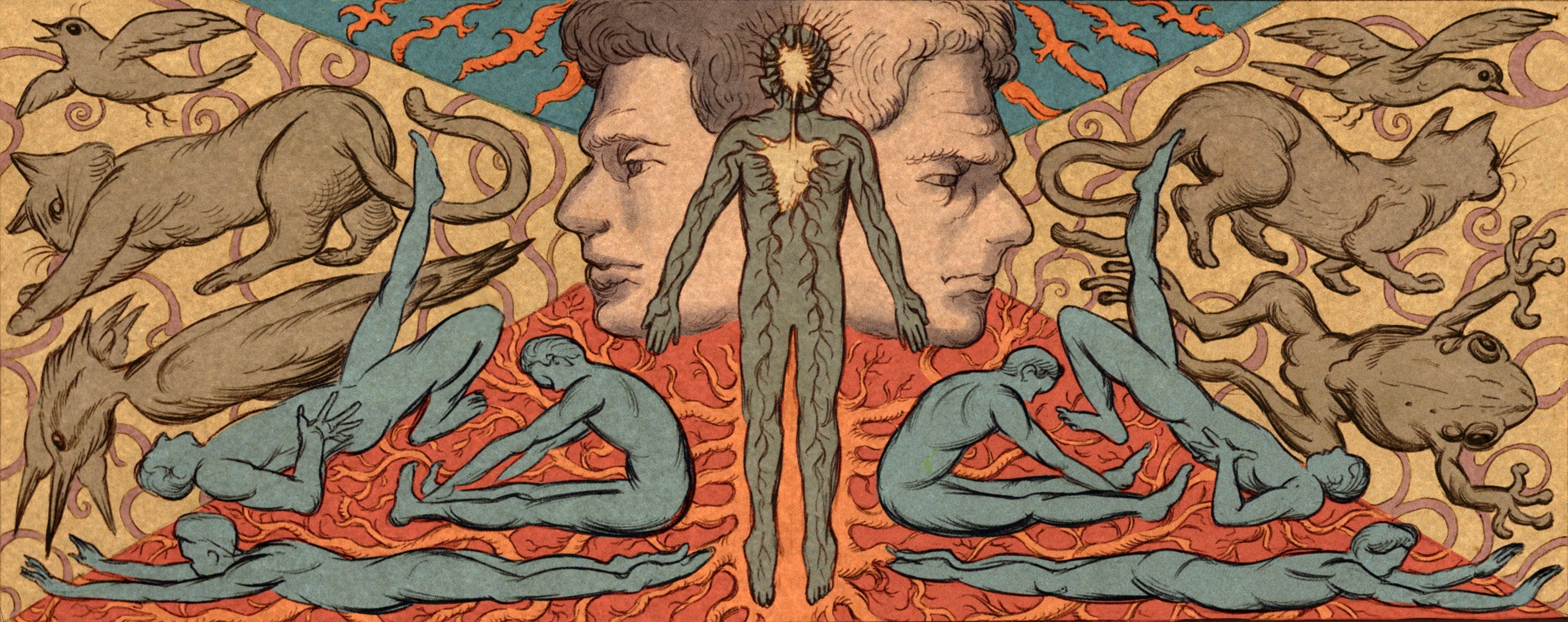

But amid the anonymity of the camp, one of the men, Internee #14001 J. Pilatus, might have stood out that September day. Lithe and broad-chested, he moved with notable athleticism. His physique possessed artistic beauty, as if a Michelangelo sculpture had up and left Rome.

With the others, Internee #14001 J. Pilatus — his index card was incorrect; his real name was Joseph Pilates — was led to Camp 4, issued a bunk bed, and assigned a chore. For most of his fellow internees, this marked the start of a prison sentence, years of “nothing to do, nothing at all.” But for Pilates, confinement paradoxically offered a kind of liberation. As the German U-boats sliced toward Allied vessels and the Great War raged on, and as months gave way to years on Man, Pilates explored a question that he had pondered since childhood: Could he reimagine the capabilities of the human body through an anatomically based method of training, taking inspiration from scientific treatises, the carefree movement of children, and the dexterous ease of cats?

On the craggy isle, Pilates found a laboratory. “I had time to consolidate the method, and I had the opportunity to work with gentlemen who were coming in with different problems, different ailments,” he once said.

While the method became popular among a select group of professionals following the Great War, it was in the decade after World War II, an era of market reform and global cultural interconnectivity, that the practice really took off, with everyone from dancers in the Berkshires to New York socialites and Los Angeles stars adopting it. Pilates introduced one of the most consequential revolutions in exercise since yoga, overcoming toxic trends characteristic of the burgeoning 20th century fitness culture: He did not offer clients the bulging muscles of icons like Charles Atlas, nor did he indulge the commercialized obsession with idealized, beach-ready physiques. In fact, he did the opposite, seeking to provide everyone, from office workers to ballerinas, with a life of greater motion and bodily rhythm. His motto — “Mens sana in corpore sano,” or “A sane mind in a sound body” — came from the ancient Athenians. For new clients, however, he framed the purpose of the practice more simply: It was about relearning how to move like an animal.