The First Guy to Break the Internet

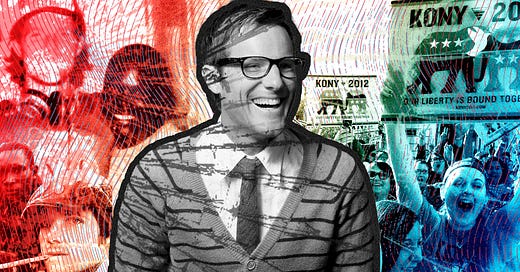

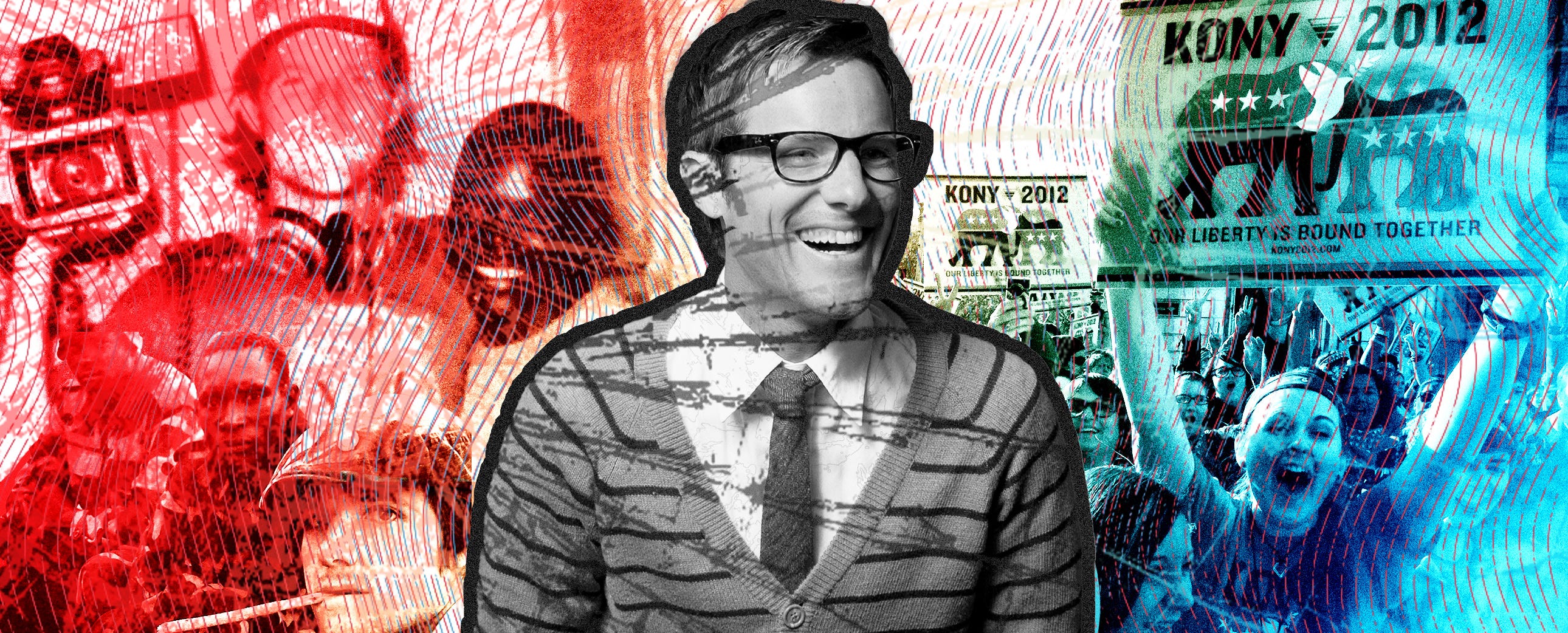

It was the halcyon days of social video, eons before TikTok, and one gung-ho idealist had a simple plan to change the world. His Kony 2012 campaign crushed the internet—and nearly crushed him, too.

March 5, 2012. The staff of the San Diego nonprofit Invisible Children had been working around the clock for the past several months. Now, the exhausted and exhilarated crew gathered round Director of Communications Noelle West’s desk as she typed “YouTube” into her browser and pressed “make public” on the 29-minute-long video that, according to the video’s narrator, would “change the course of human history forever.” At midday Pacific time, Kony 2012 went live. A beat. A sigh. The view count hardly budged. Everyone returned to their seats.

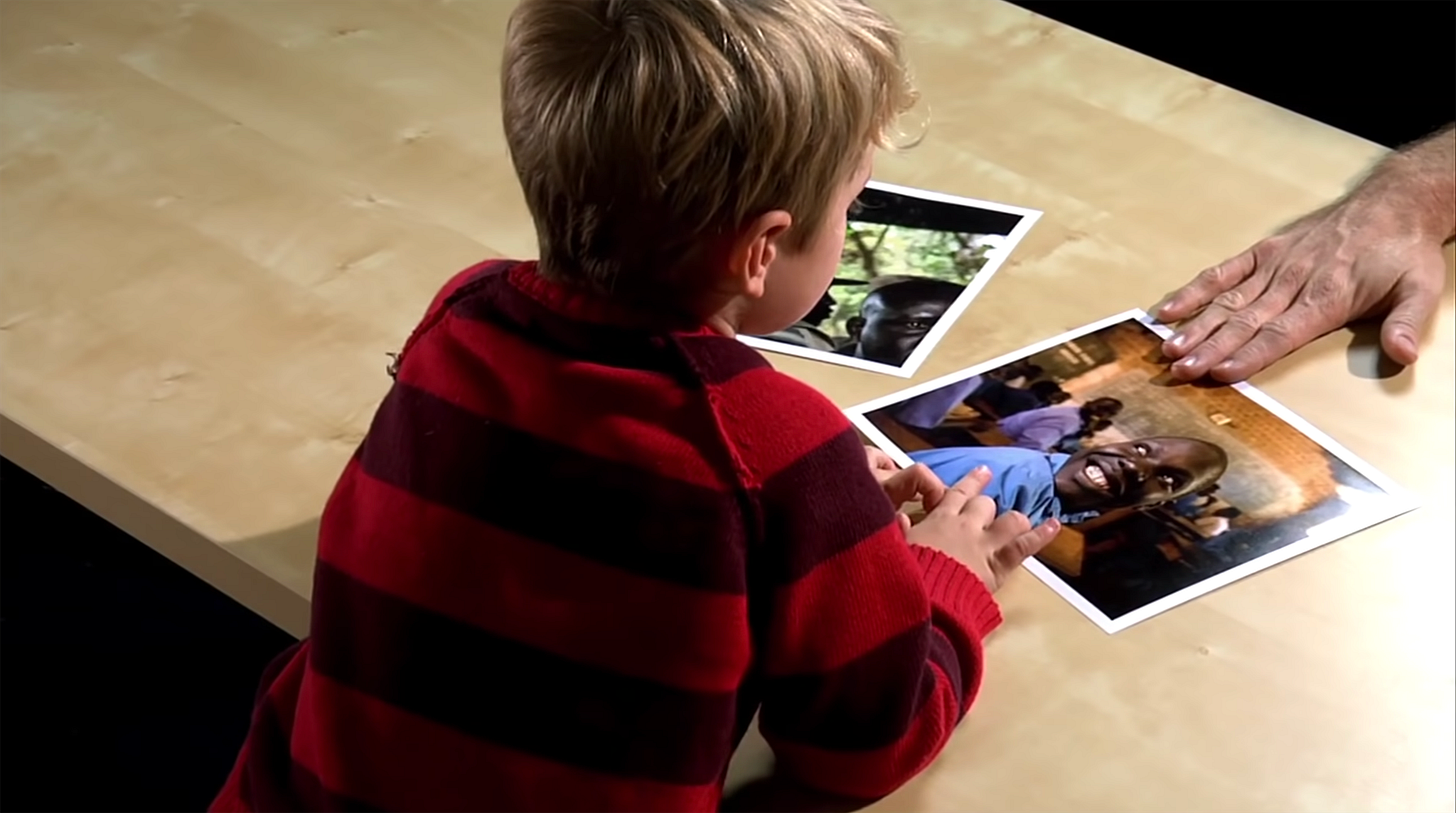

That night, Jason Russell, the video’s protagonist and Invisible Children’s then-33-year-old co-founder, was in Los Angeles alongside his wife, Danica, and 5-year-old son (and Kony 2012 co-star), Gavin, leveraging the modest Hollywood connections he’d made to drum up excitement around the video. He premiered Kony 2012 at the talent firm Creative Artists Agency, with an event hosted by Jason Bateman and family friend Kristen Bell. Around 200 people were in attendance. After the screening finished, Jason checked his phone. Things were going well so far. With help from a nationwide network of high school students the Invisible Children team had spent months cultivating, the video had climbed to 200,000 views. By midnight, it had reached 500,000, which was their goal for the entire year.

Then, Jason awoke in the middle of the night to a flurry of texts, all saying some variety of the same thing:

“Jason, Oprah has tweeted the video.”

One tweet from the Queen of All Media set the video on a stratospheric trajectory. Jason began receiving messages from late-night TV hosts requesting to interview him, and from celebrities like Justin Timberlake who wanted to show their support. It was a tsunami of accolades and Jason was quickly overwhelmed. To this day, many of those messages remain unopened.

The next morning, Jason drove from Los Angeles to Invisible Children’s office where dozens of strangers were milling about, filling the parking garages on either side of the fifth-story office, all wanting to meet Jason and his team — either to help out or to pitch business ideas of their own.

When Jason entered the conference room in front of the main office space, not a single head turned to face him. Siloed in their cubicles, each member of staff was incessantly pressing refresh on YouTube, gazing at their screens in a trance as the view count climbed by the millions:

Two million. Refresh. Three million. Refresh. Four million. It didn’t stop.

Kim Kardashian was tweeting about it, Rihanna was tweeting about it. Justin Bieber was tweeting about it. Then, the office’s internet crashed.

“Can anyone help me?” Jason asked. No one even looked up.

Jason grabbed Alex Collins, the artist relations manager, by the arm. “Help me,” he said.

“Can’t. Working,” Alex replied before returning to his seat.

Jason left the office and returned 15 minutes later with a wheelbarrow filled with bottles of Champagne, pushing it into the conference room. No one noticed. “Everyone in here!” he yelled. No one budged. They were glued to their computers, trying frantically to keep up with the video’s wild spread. “We are so fucking busy,” Jason heard someone say, while alone in the conference room with his wheelbarrow.

The entire world felt open to him. Because of him, a new generation of internet-raised digital natives would know revolution, true community, peace. Because of him, the most wanted international warlord would be brought to justice. Because of him, evil would be destroyed, and love and goodness would forever prevail.

All this, and not a single member of his staff would give him a simple gesture of acknowledgement.

Jason left the conference room and banged on a table: “We. Are. Celebrating.”

Finally, the staff obeyed their leader — for a few moments. For 15 minutes, they popped Champagne and spiritlessly celebrated. “That was the only time we had any kind of celebration,” Jason says.

That video — Kony 2012 — is an artifact of unprecedented viral success, reaching 100 million views in only six short days. At the time, it was the most viral video in YouTube history. And it is difficult to overstate how unlikely it was for this particular video to take that crown. YouTube had already proven the ability to reach Super Bowl-size audiences via web video, but the other most viral videos of that year were all either catchy pop hits like Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe,” cultural sensations like Psy’s “Gangnam Style” or political sendups such as “Barack Obama vs Mitt Romney. Epic Rap Battles of History.”

Kony 2012, effectively a social advocacy video, was a viral anomaly. The campaign centered around Joseph Kony, leader of Ugandan guerilla group the Lord’s Resistance Army and, according to the video, the most evil man you’d never heard of. The viewer was directly challenged: Keep watching for the next 29 minutes, make Kony famous, change the world. It proposed an irresistibly simple and slick call to action, gamifying a pre-organized strategy: Share the video with friends; tweet it to celebrities and government officials; take to the streets. If all goes to plan, a groundswell of grassroots activism will compel the U.S. government to intervene, sending out troops to capture Kony.

The Arab Spring — a pro-democracy uprising across several countries, triggered by viral footage of a young Tunisian man who set himself ablaze — had recently fueled a narrative about the democratic power of social media. Arriving in its wake, Kony 2012 spoke the language of techno-optimism. It was a time when there was an ambient faith that digital democracy practices and social networking technologies could inspire mass mobilization against centralized, oppressive hierarchies. The internet could inspire a global manhunt. Viewers could help catch the real-life villain, defeat the evil. All you had to do was share the video.

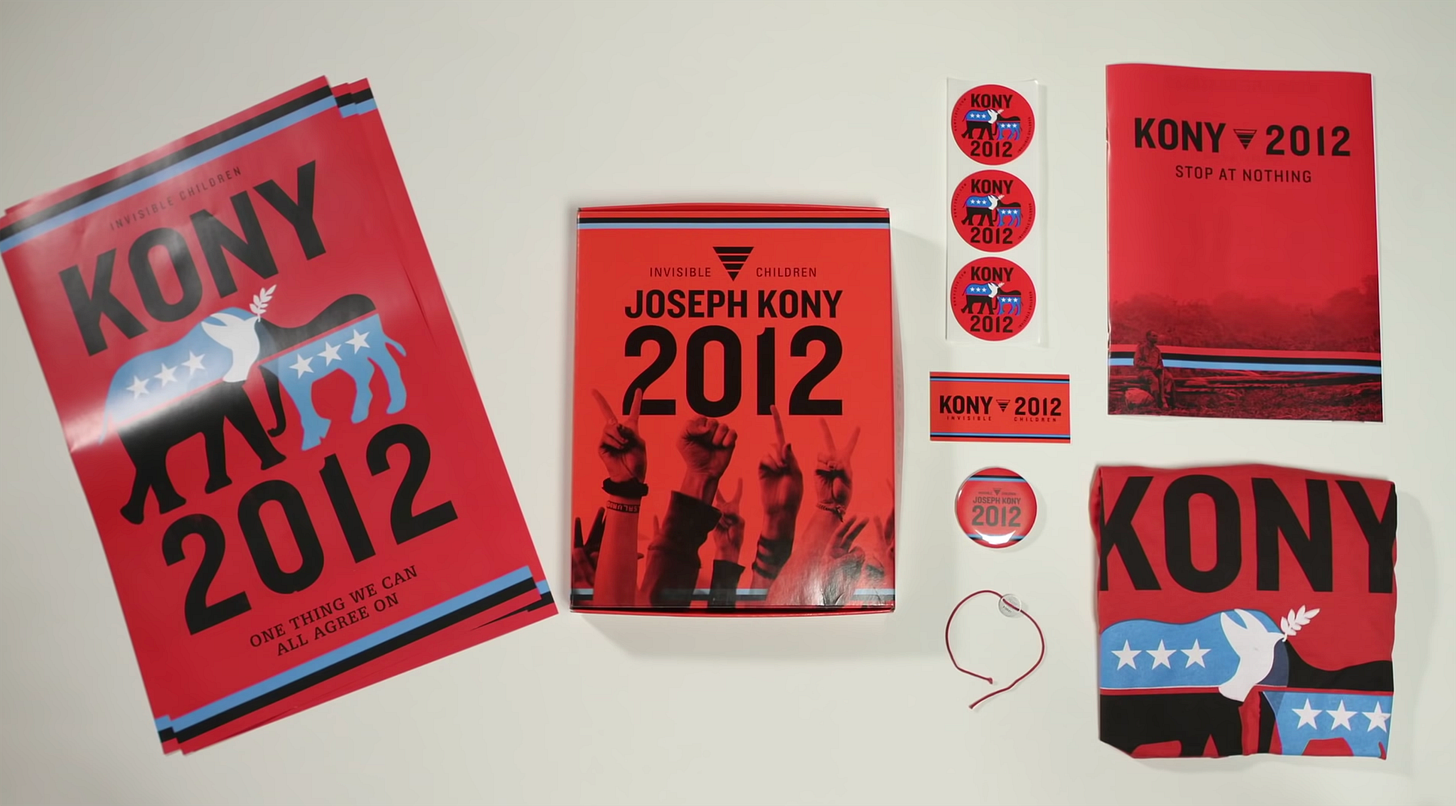

In the days that followed Kony 2012’s release, millions of Westerners previously numbed to charity footage of suffering Africans were suddenly inspired to take action, not only sharing the video, but also purchasing $30 kits filled with posters of Kony that they intended to spread around the streets.

Then, just as quickly, it all fell apart.

The internet was unable to follow through on its promise to materialize the utopia we thought it capable of. Millions of people threw those same posters into landfills, laughing off their brief fervor like an adult looking back on a bad haircut. In less than one week, Jason Russell went from complete anonymity to worldwide celebrity to canceled villain to laughingstock, his very public “naked meltdown” mercilessly mocked across the web. Kony 2012 did not forever alter the course of human history. Instead, it has become a digital relic of deep hubris. Those who recall this frenzy remember it mostly as a tragic joke. Kony 2012 has become the stuff of shitposts and ironic halloween costumes at millennial-themed house parties.

Kony 2012 may not have delivered the revolution — nor, notably, its promise to capture Kony. But it did, perhaps, presage the way in which democratic discourse takes shape online today, nudging a cultural shift away from tech optimism toward skepticism, and creating a more discerning, media literate class of online users. It also, very much unwittingly, kick-started conversations around two issues that now dominate our discourse: cancel culture, and the rise of disinformation. It served as an early look at the psychological consequences of flash viral fame, and it inspired the mainstreaming of the term “white savior,” which was used by Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole to describe Jason Russell and the phenomenon of Kony 2012. “The banality of evil transmutes into the banality of sentimentality,” Cole wrote in one of his series of viral tweets criticizing the video.

“White Savior. I think it’ll be the name of my movie — and book,” Jason tells me 11 years later, hair slicked back, smiling. “I even bought the whitesavior.me website domain. It wasn’t very much, only $15.”

Jason meets with me across multiple locations in Los Angeles, showing up at various bars and cafes in a red Corvette. He is charming and deeply sincere, warm and empathetic. He carries himself with total openness, as though he has nothing to hide. He is self-deprecating when he feels corroborated with; defensive and self-congratulatory when he feels challenged. Despite everything that happened, he still feels that creating Kony 2012 was his destiny.

“Had I not become a ‘white savior,’ that would have been shocking,” he says. “I was trained to make a difference, make an impact, go for your dreams, help people. How far can you blame a person when the environment, the culture, the community, the nation, the religion, groomed them to be a very specific way?”

Jason Russell was born in San Diego in the fall of 1978. He attended a Christian kindergarten before studying at Anza Elementary, where he was under the tutelage of Mr. Dorfi, a sentimentalist who cared deeply about his students and the injustices in the world. He left a deep impact on young Jason. “He was everything you wanted a teacher to be. He was very emotional, he cared so much about us. And he was [full of conviction] when he told us about the Civil Rights Movement and about slavery,” Jason says.

His parents are Paul and Sheryl Russell, the founders of the Christian Youth Theater, the largest national youth program of its kind in the United States. By the age of 12, Jason says he “wouldn’t be surprised if I had 10,000 hours” of musical theater experience. He had been the Tin Man and Mr. Toad, but at 13, he landed his dream role: Peter Pan. In Peter, he saw his desires, and he saw himself. He, like Peter, was a storyteller who longed for eternal youth and the ability to take flight. On stage, he got his wish. Underneath his green tights and shirt, he wore a flying contraption, allowing him to perform backflips midair. He flew through a window. He flew past the fireplace. He flew into the audience.

“Peter Pan is just such a poignant story to me,” Jason says. “I think it’s all about the wisdom of youth, and it’s about the ultimate protection of children. Peter Pan runs and lives in an orphanage, protecting babies that fell out of their carriage the day they were born.”

But Jason’s real life was far from a fairy tale. Backstage, he was being sexually assaulted. Jason says his predator was the person responsible for putting him into his harness, allowing him closer access to Jason’s body.

“It happened for a long time, definitely about two years, between the ages of 14 and 15. I think it stopped at 16,” Jason tells me.

Jason was one of many victims of alleged grooming and sexual assault at Christian Youth Theater. In July 2020, alongside Jason, dozens of former students came forward with allegations of sexual abuse, racism and homophobia. The unnamed plaintiffs alleged that numerous adult instructors had given boys as young as 8 alcohol, before touching them inappropriately on multiple occasions. CYT, it was ascertained in court, created an environment where predatory behavior went unchecked. Paul and Sheryl, the students alleged, turned a blind eye to it, even encouraging their instructors to attend sleepovers and trips with the children.

“You were your parents’ invisible child,” Jason’s therapist told him after the fallout. “No wonder you wanted to protect invisible children.” Though he’s no longer close with his parents, Jason is careful not to place the blame on them, referring to them as “good people” who simply made bad decisions.

“It’s interesting that the special about Michael Jackson was called Leaving Neverland,” Jason says, “ and I very much resonated with it. When it came out I was like, ‘That is my story. Yeah, that is my story.’”

In his first year of college, Jason made a short film about Peter Pan in Neverland, before spending the summer with evangelical Christian youth organization Teen Mania (which has since shut down). Each year, the organization held enormous conferences in cities across the U.S., packing out stadiums with thousands of teenagers there to sign up for missionary trips. Jason, who wore blond dreadlocks at the time (“I was breaking all the rules”), attended one such conference, before spending a summer week training in Texas.

Jason traveled to Kenya with Teen Mania in the summer of 2000, performing 30-minute productions alongside 150 others, dancing around in costumes and offering up the word of the gospel. At the end of each production, they’d tell the villagers to raise their hands if they wanted to be saved — before heading back to their hotel in an air-conditioned minivan. In the U.S., criticism around the organization’s militaristic symbolism and training regimes grew. Teen Mania’s website battlecry.com, for instance, was decorated with a blood-red logo, battle flags and text that encouraged teenagers to “join the frontline.”

Gradually, while taking those air-conditioned minivan rides and reading about the criticism of Teen Mania online, Jason realized he wanted to approach this all differently. He was compelled to return with a camera, intent to embed himself in the lives of the villagers rather than feign help from a distance. He wanted to show the Western world what life was like

“out there,” through his lens.

In the summer of 2002, while working at a theater camp, Jason told his friend and campmate Bobby Bailey that next spring, he was “going back to Africa with a camera.” Bobby was adamant on joining him. Jason, however, was actually growing sick of Bobby, and was determined not to spend another several weeks with him. He held fast: “Or maybe you could not,” he said to Bobby. As lifelong students of Christianity, Jason and Bobby had spent much of that summer arguing back-and-forth over the issue of whether life was predetermined or whether one entered it with a free will. Jason was in the free will camp, while Bobby, a Calvinist, was in the former. They argued every day, past lights out, reaching the point of exhaustion and frustration. Neither was capable of changing the other’s mind. This disturbed Jason, a raconteur.

“It’s kind of ironic that I now have this tattoo,” Jason says, pulling up his plaid sleeve to reveal his inner wrist, veins spread across it like mud cracks, the word “timshel” in typewriter font imprinted on top of them — a reference to John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Jason’s favorite novel. “I think the big takeaway of it is whether or not we as beings are capable of free will, and ‘timshel’ [means] ‘thou mayest’ [in Hebrew], as in, you have the choice of whether or not to overcome sin.”

By Christmastime, Jason had decided on his location, a rather unorthodox choice: war-torn Sudan. But he hadn’t found anyone else brave enough to join him and was facing the prospect of traveling there alone. He returned to Bobby, begging and pleading with him. “You’re a jerk, you know that?” he said to Jason, before relenting

Together, they tried to recruit Laren Poole, a then-lifeguard they were becoming close friends with, who had his own ambitions of directing blockbuster action movies. Laren, who was also on the side of Calvinism, said he would need “a sign.” Jason and Bobby took this literally. The following day, they broke into his unlocked car, played classic rock group Switchfoot at full blast — effectively snake-charming music for a Christian millennial — and held up a sign that read “GO OUT” in pink spray paint, outside of his house. It was an evangelical John Cusack move that drew tears from Laren’s eyes. “I’m going, I’m going, I’m going,” he said, on the phone to Jason and Bobby. “I don’t care if I die,” he wrote later that night in his journal.

Soon after, Jason wrote to none other than Oprah Winfrey, telling her about his trip to Africa. He signed off, thanking her. In Oprah, he saw himself. “As soon as I first saw her on TV I remember just being drawn to her light and her essence and power. So, I would make personal videos from me to her, and I knew how to message it to her. I knew how to speak her language.”

When Jason appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show years later, she thanked him for the videos.

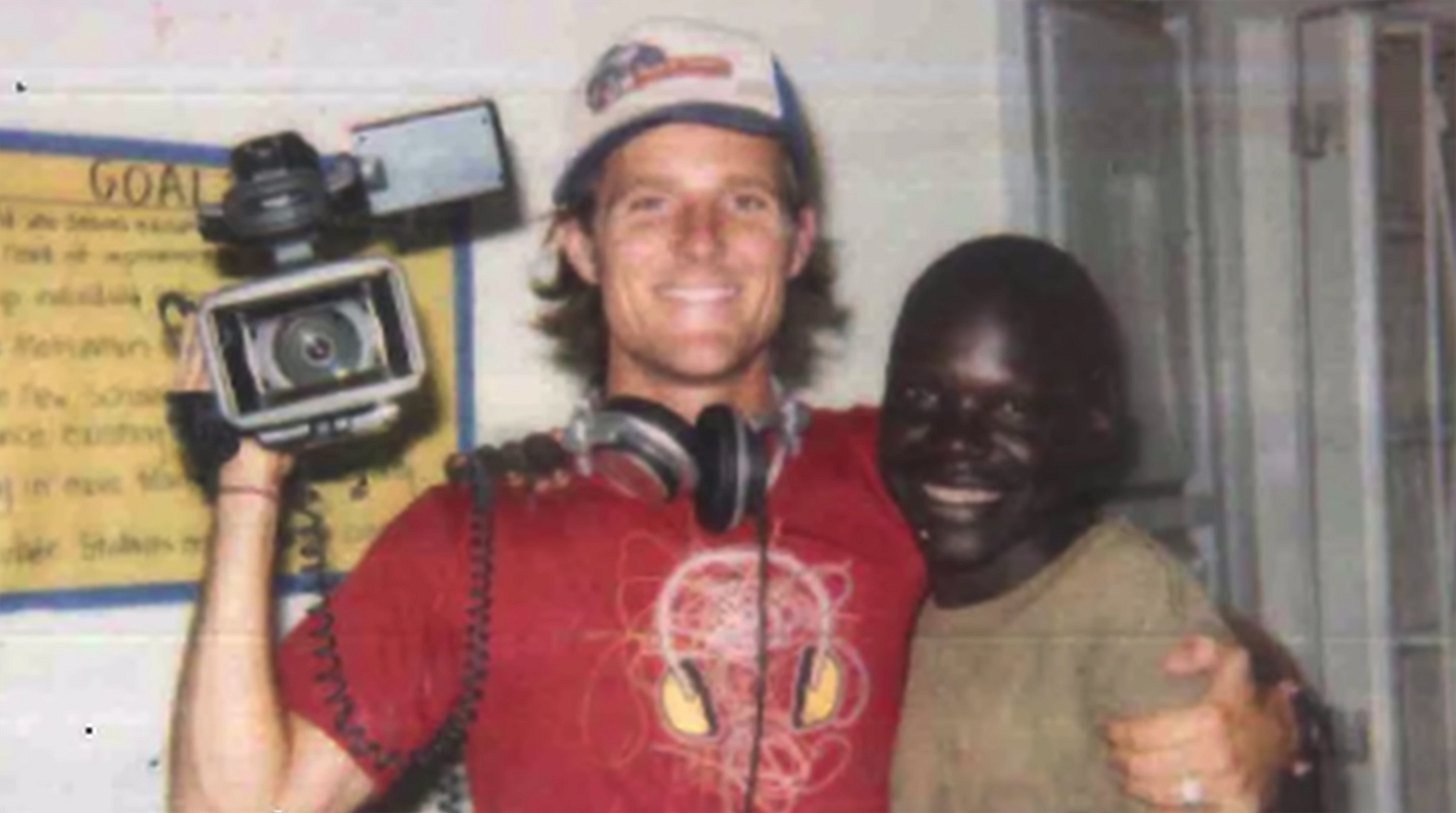

When the three unaccompanied recent college graduates arrived in Sudan that following spring — just as the genocide in the western region had reached its height — Jason says they were the only white people there, “except for a guy named Jeff. It was so dangerous.” Their cameras, he says, gave them “a sense of empowerment — but not even just empowerment — of responsibility.”

While they originally intended to document the humanitarian crisis in Sudan, when they arrived, there was scarcely any activity to shoot. A local woman they met on the road redirected them to Gulu, in the northern region of Uganda, telling them that was where they’d find their story. When they arrived they found children sleeping on the streets, children who told the white men with cameras about Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army.

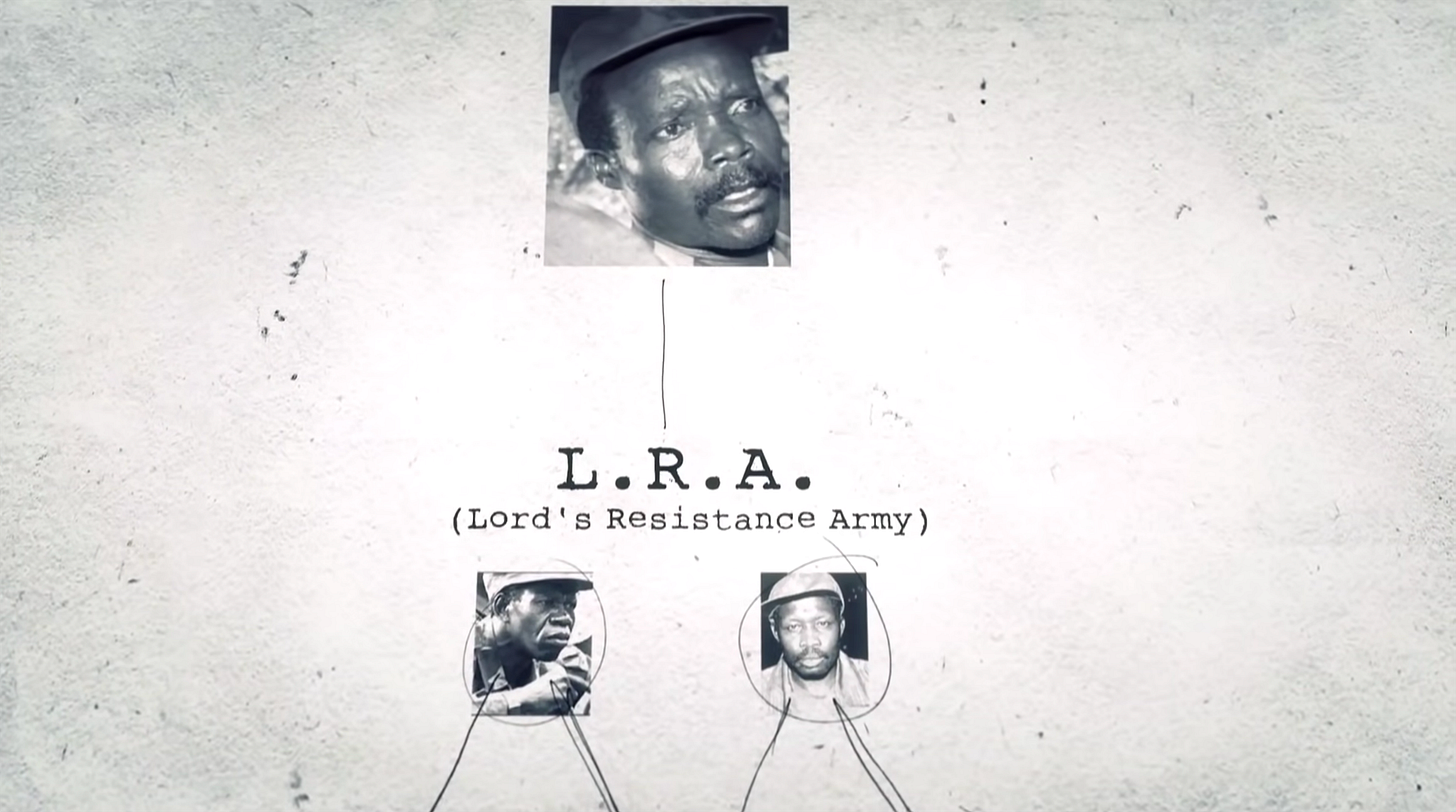

Kony had come to prominence in the 1980s as the leader of the L.R.A., a military force that supposedly existed to combat Yoweri Museveni, the reigning president of Uganda who took control of the country after he led his own child soldier-assisted rebellions in 1986. In the decades since, Kony has abducted tens of thousands of people — mostly children — inducting them into the L.R.A and displacing them from their homes.

The children told Jason, Bobby and Laren stories about the rebel army mutilating the faces of their friends and raping them in front of their schoolmates; of the torture techniques that would leave them begging for death.

Jason became particularly attached to one of these children — 11-year-old Jacob — as he recited the story of his brother’s abduction by the L.R.A. Jacob had aspirations of becoming a lawyer. He spoke lucidly and emotionally about the impact of Kony on his region.

“We are going to do everything we can to stop them,” Jason told Jacob, a promise that is central to The Rough Cut, Invisible Children’s first film, and to Kony 2012.

When Jason arrived back in San Diego, he rented out an office downtown and began to edit the footage from Sudan and Gulu. The partitive images didn’t initially seem to resemble a story or amount to a whole. Then, came Jason’s epiphany: What if the viewer was the story? What if viewers’ lives could change based on the movie they’d just watched? What if they didn’t passively consume the piece of media, but were instead active participants who were ultimately called and roused to action?

In The Rough Cut, Jason, Bobby and Laren centered their own naïvety, playing into their frat-boy personas, as they featured footage of themselves setting snakes on fire (Jackass was popular at the time).

“There’s a rule in storytelling: Your hero can never think of themselves as better than anyone else,” Jason says. “We were telling an honest story. And we were saying, ‘We don’t know what we’re doing. We came here to find a story.’ And, oh my God, did we find a story.”

Jason concedes that he was more interested in winning an Oscar than becoming the director of a nonprofit. They sent The Rough Cut to Sundance, but were rejected. “If we got into Sundance, there would have been no Invisible Children,” Jason says. While Bobby went back to school and Laren began to work, Jason, who was fueled by resentment, made his own Sundance instead. Only, rather than a film festival, it was a nonprofit.

Invisible Children’s strategy was unique. Creative storytelling was at the center of its mission, and around 43 percent of its budget was spent on “awareness programs,” including media production. Humanitarian aid was posited as a means of mutual self-empowerment, of belonging to an impassioned collective. “I feel like that posture contributed to a lot of people wanting to feel involved,” Jason says.

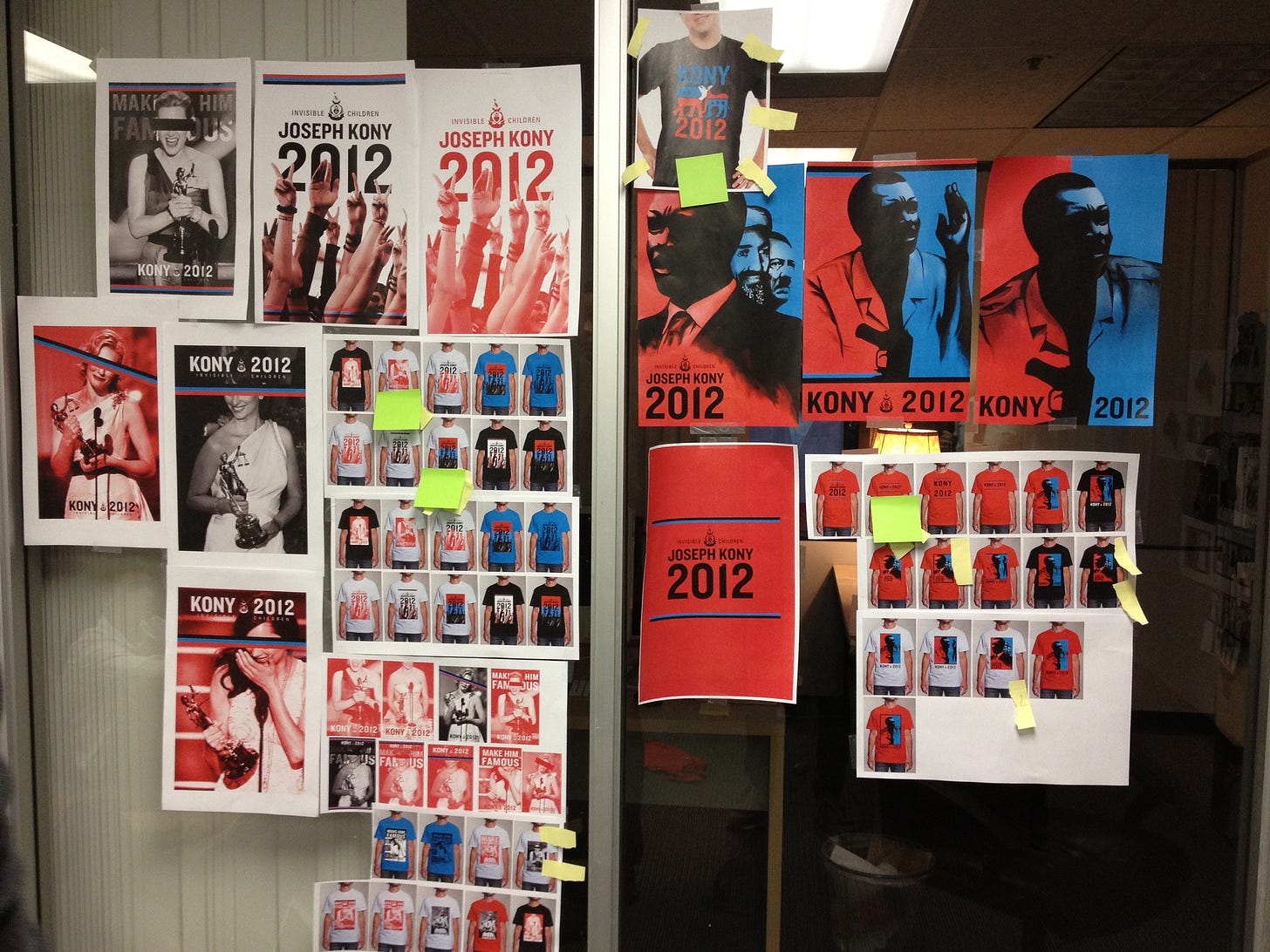

Spreadability was baked into the team’s strategy from the start, though they originally relied on pre-digital tools to disseminate their message. They created posters for distribution across college campuses, sticking them on students’ doors along with three copies of Rough Cut, and instructions to “take it,” “watch it,” “return it.”

Jason was trying to target a specific demographic: white, middle class and popular. “We wanted to go after those types because then it would trickle down,” Jason says.

Prior to Kony 2012, Invisible Children made nine films which they presented across 15,000 screenings to a direct audience of five million. Varsity soccer players cried during screenings. Teachers and students alike said that the films changed their lives. The idea that Kony 2012 suddenly went viral obscures the years of grassroots work that preceded it. “We kind of ran Invisible Children like the military,” Jason says. It was a full-scale operation that instilled in its followers an urgent sense of life-or-death stakes. An us-against-them scenario.

In those years, Jason was rapidly spreading himself thin while traveling to screenings across the country. He needed to expand his team so he could stay in the office and strategize while others screened his films on the road. The way to do that, he figured, was to recruit ambassadors for the Invisible Children brand: young students willing to work for free and compete for the chance to spread the word of Invisible Children throughout the States. “Once you made it in, it was like a bootcamp for activism,” Jason says. He referred to the Invisible Children ambassadors as “roadies.”

Invisible Children rented out a house in a residential area of San Diego for roadie recruitment and training. There, around 40 to 60 roadies at a time would learn in greater depth about the history of the L.R.A., as well as bookkeeping, managing spreadsheets and navigating Salesforce. Then, they’d split up into state-based teams of around five to six, accompanied by a student from Uganda, and travel around the country, showcasing the films and spreading the word about Kony.

“One of the things they had us do that I’ll never forget was watch a video called Last Moments with Milo,” Saul Malone, a writer who worked as a roadie around the time of Kony 2012’s release, tells me at a cafe in Los Angeles. The six-minute video featured a man’s final moments with his dog — on a walk, a bike ride, a car ride — before putting him down. “Yeah, it was pretty sad,” Saul says. Three weeks later, after intensive training, Invisible Children screened the video once more, aiming to demonstrate the impact of highly emotional content, the kind that was baked into each of their films. “Watching the video just that one time was tough, but this time, everyone broke down crying,” Saul recalls. “I sat there and I wept.”

The sleeping situation — which Jason says wasn’t dissimilar to their setup in Gulu — “was probably not legal,” Justin Peterson, a doctor who also worked as a roadie at the time of Kony 2012, tells me. (Both Saul and Justin are now in their early 30s.) Justin slept in a room the size of a typical suburban teenager’s bedroom with around 24 other young men, their beds stacked on top of one another in military fashion. “One or two people didn’t have beds so they’d have to find somewhere random to sleep,” Justin says. “I think one of them slept in a closet.”

Meanwhile, as more staff came on board, the sense of urgency to capture Kony increased in the Invisible Children office. Inside, it was like a boiler room, the workers buzzy and sweating with excited and agitated energy. They brought their sleeping bags into work and spent nights editing footage, strategizing, campaigning until sunrise, occasionally sleeping beneath their desks, or on a co-worker’s couch.

“Here’s the thing about people that worked at Invisible Children. Nobody liked to talk shit behind people’s backs. Nobody liked to gossip,” Kevin Trout, a California native and one of Kony 2012’s lead editors, recalls. The majority of people gladly worked there for free, or for a salary that hardly paid the rent. Many of them were recovering evangelicals, almost all white millennials in their 20s. They had been taught to serve others as children, but after graduating college and becoming disillusioned with their childhood faith, found that there was no one to serve or save. Jason, like Captain Hook in Peter Pan, felt the ticking of the crocodile clock each second Kony was still at large. And he made everyone else feel that urgency, too.

Jason was a magnetizing figure. Still to this day, he carries himself with the conviction of a child who believes he has magical powers. He narrates his own life to me like an oracular storyteller. While there’s now a sense of pathos to his dogged earnestness and wide-eyed passion, when he was the captain of Invisible Children’s ship, he inspired deep reverence from just about everyone under his command. “It’s his charisma, his deep need to do good for the world,” says Andrew Collins, the brother of Alex Collins, the former artist relations manager. “When I went to visit the office, he was so excited to introduce me. I wanted to do anything I could to live there 24/7.”

In 2010, Congress passed a counter-L.R.A. program bill, signed into law by Barack Obama, which meant that the State Department would spend some $1.2 million a month for two helicopters to surveil the greater Ugandan area and aid in the capture of Kony. For Jason and others devoted to stopping Kony, it was a start, but far from enough.

While working in D.C., trying to keep the heat on senators and members of Congress, Michael Poffenberger of L.R.A research and advocacy program Resolve, phoned Jason after a somewhat unsuccessful afternoon. “If Kony was famous, then we’d get more meetings,” he said.

“I remember it hitting me like a lightning bolt,” Jason recalls. “Make. Kony. Famous.” He began skipping and running down the office hallway before taking a book on Andy Warhol from the shelf and making his creative team study the concept of fame: what it is and how celebrities leverage it in order to influence others.

In their early designs, the Invisible Children team photoshopped Angelina Jolie in a meeting with Joseph Kony; women with mutilated faces on the covers of Vogue. Then, they developed an action kit: a $30 package containing a T-shirt, bracelet, badges and flyers to spread across the recipient’s neighborhood. “We treated the work that we were doing as though we were working at Nike or Apple, a brand. We knew we were competing for eyes, hearts and minds,” Jason says. “We were using that same kind of integrity and intensity to beat the drum about this story. We weren’t afraid to spend resources to do that in order to gain more people. It was incredibly radical for a nonprofit to do the kinds of things that we were doing.” While it may not have been quite as groundbreaking as he makes out — he was taking a leaf out of Bono’s book when it came to combining humanitarianism with corporate brand culture — Jason was uniquely talented when it came to branding a humanitarian crisis.

As for the video itself, Jason wanted to “do something that had never been done before”: directly address the internet viewer, making them feel both culpable and empowered, before daring them to keep watching.

Kevin Trout had been brought in to digitize the footage from Gulu. “Man, there was some dark stuff, dude,” Kevin tells me on a Zoom call. Every day, he’d have to pore over clips of children crying out in emotional agony, recounting stories of their family members’ violent kidnappings by the L.R.A. He spent months with the recordings, coming to know the footage more intimately than anyone else, going home each night numbed.

Kevin, alongside a team of five others, edited meticulously. They had a seven-second rule in which they asked themselves, “Do these seven seconds keep you engaged? Do they lead perfectly to the next seven seconds?” They cut and cut until they had a video just under 30 minutes in length. The arrangement of the video was cinematic in scope with short frame times.

The roadies were shown Kony 2012 a week before hitting the road to promote it and around a fortnight before its public release. “I kind of had mixed feelings, to be honest,” Justin, the roadie, says. “I felt like, compared to their other films, I thought this was very much a kind of flashy call to arms sort of video.”

Part of the punch of Kony 2012 is its simplicity, the positioning of partial fact. A more detailed and rigorous video may have mentioned the South Sudanese peace talks, which occurred between 2006 and 2008 and led to the removal of the L.R.A from northern Uganda (as well as the slipshod U.S.-enabled military strike in 2008 that effectively terminated those peaceful negotiations and resuscitated the war). It may have detailed the complicated relationship between President Museveni and Kony — it may even have positioned Museveni as its primary target rather than Kony. “If you survey any Ugandans right now … and you ask them a basic question, ‘Who actually caused more destruction and deaths between the Uganda military and the L.R.A.? I don’t need to give you the answer,” Ugandan-American writer Milton Allimadi tells me. “The child soldiers originated with Museveni himself. He had child soldier bodyguards.”

Sangita Shresthova, a director of research at the University of Southern California, who led a research project on Invisible Children from 2009 to 2014, noticed a number of tensions within the organization, all of which eventually surfaced around the time of the Kony 2012 campaign. The main one, she says, was the tension between wanting to tell an easily digestible version versus the complex story of the L.R.A. that needed to be told. “We saw the shortcomings of their approach, because once it was made visible in the way that it was, it was subjected to critique that they weren’t prepared for, and should have been,” Sangita says.

To this day, it’s a criticism that Jason still rejects. “To the people who say I oversimplified the situation, I say ‘thank you’ because simplicity is the highest form of sophistication. It’s actually very sophisticated. That movie is layered and sophisticated and thought through of how to get you to keep watching.”

When Kony 2012 went viral, Jason was swept up in a simple kind of joy. He felt the world on his side — for a brief moment. Many of the world’s biggest celebrities — Angelina Jolie, Lady Gaga, George Clooney — were urgently telling the public not to sleep on the video. The public donated hundreds of thousands of dollars within the first 24 hours of it going live. Kony 2012 was suddenly the world’s number one topic of discussion.

“As everything does on the internet, after three days, things swing the other way,” Jason says. “That’s typically when you start to see the backlash.”

Jason stopped sleeping on that third day, as the pendulum firmly swung away from him.

“We realized quickly we were getting a lot of the same criticisms over and over, so we split up to try and conquer each one,” says Krista Morgan, one of Invisible Children’s writers. Key among those criticisms — in addition to the video’s oversimplification — were charges of neocolonialism and the disempowerment and occlusion of African voices. Around the time of the video’s release, Ethiopian writer and activist Solome Lemma wrote in a now-deleted blog post that she was disturbed by “the disempowering and reductive narrative” on display in Kony 2012. “[It] paints the people as victims, lacking agency, voice, will, or power. It calls upon an external cadre of American students to liberate them by removing the bad guy who is causing their suffering,” she added.

Other commentators took issue with the video’s call-to-action for military intervention, and the naïvety of the potentially destructive consequences of such a strategy. “Any sensitive, long-term or balanced observer of events in the region will explain that Kony continues to survive and draw strength because of the militarized nature of the region,” wrote activist and author Matt Meyer.

By this point, the roadies had been traveling across the States for three weeks, and were now receiving an increasing sense of animosity with each stop. The attacks became more personal: High schoolers ripped their posters apart right in front of them. The roadies said some of them were sleeping 20 minutes a night while driving upward of 14 hours a day. They still had seven weeks left on the road.

In the office, the staff had only one P.R. person to rely on, an intern. “We had to have responses, not only to Joe Shmoe asking on the internet, but also reputable sources,” Krista says. “We weren’t prepared. It was a really tiring time. And it just got harder and harder. The criticisms got worse and more.”

Jason tried to field some of those criticisms on a press trip to New York, where he sat down for around 17 interviews. When he got to the terminal at the San Diego airport on March 8 to catch a red-eye to New York, Kony 2012 was playing on the TVs across the terminal. “Tell Gavin we say hi,” two girls said to him on the escalator, laughing. The woman sitting next to Jason on the plane told him she didn’t like his film, and turned away from him for the duration of the flight.

Jason arrived in New York at 3 a.m. When he got to his hotel, his transport for the Today show was already there waiting for him. Jason was still living his dream. The world knew about Kony, the world knew about Jacob. At 7 a.m. — when the Today show went live — that dream began to slowly dissipate. The tone of those interviewing him had done a complete 180 from the first few glowing days. “This isn’t how it works,” Ann Curry told him, hinting at the video’s oversimplification. From there, he took a car to his interview with People magazine, then The New York Times, then Reuters, then a few more news shows. When Jason returned to his hotel late into the evening, the heartbeat in his ear was so loud it prevented him from sleeping.

The next day, he met with Sunshine Sachs — a P.R. firm that specializes in helping celebrities through major public crises. But Kony 2012 was too big; insurmountable. Jason says they told him that they’d never encountered anything like it; there was no way they could spin the story to help him regain control of his own narrative.

It wasn’t until later that day that Jason’s typically high spirits began to diminish. Ennervated, devitalized, he turned on a computer for the first time in days and read an article about himself on a popular website. “This guy is clearly gay,” he remembers a caption beneath an uncomplimentary photo of him read — repeating a suspicion that followed Jason throughout the campaign, due to his perceived campness and theatricality. For the first time, Jason realized that Kony 2012 had become a bad joke. He felt burdened with the weight of himself, a dove-gray gloom surrounding him. For the first time in his life, he felt truly, all-encompassingly depressed. The train had left the station, and now, unloosed from the tracks, it was pummeling on his body with mud-slacked wheels.

Jason returned to the Invisible Children office a week later. He hadn’t slept for several days. He brought a pile of paper plates with him to the conference room and began writing out screeds on good and evil, passing the plates around to the staff. He was at the center of the universe, the diviner of morality and mortality. With the questions from his interviews still reeling in his head, he felt he had to have the answers for what was to come next; that he was responsible for the fate of humanity, every living creature. The paper plates were his best shot at saving the world.

“He was our captain, and it’s hard to watch the captain of your ship completely disintegrate,” Krista, who had known Jason almost for his entire life, says. His younger sister, Janie, has been her best friend since she was 4 years old. She had never known Jason to be unwell. “He was always very off-the-wall, ‘dream big’, ‘dream impossible things,’ but never ill. It was shocking to see how fast that happened.”

“I’m debating whether to go here or not,” Jason says with a sigh, looking at me and making sure I’m looking back with humanity; seeing him as someone who possesses sanity and humility rather than theistic delusions of grandeur. “OK, why not?” I respond.

“So, there’s something that happens to me and my brain,” he says. “I think it’s because I’m bipolar,” a diagnosis he received shortly after the video’s release. “I figured out what it’s called — the name is unitary consciousness, and it’s when everything in the world that you can see and touch and feel and hear, syncs up,” he says, forming a globe with his palms. “It syncs up.”

Jason says he experienced unitary consciousness for the first time on a trip to Palm Springs with his family shortly after the paper plates incident. Around the hotel pool, families were taking photos of Jason and his children. They retreated to their hotel room — the only place they felt a semblance of safety — and closed the windows and curtains as though they were hiding out in a bunker. They ventured outside less than a handful of times during that trip. On one such occasion, they went to a screening of The Lorax together before eating dinner at a burger joint. “The Kony guy’s right there!” a waiter said while pulling his line manager’s shirt.

“Now, what I’m about to describe, it’s probably impossible to believe. It’s like, say you have headphones on, and say you’re listening to any random song — you push shuffle and then you look toward the door and the song goes ‘the door opens,’ and then you look out the window and there’s a red car and it’s like ‘Little Red Corvette’ and you’re like — ”

I stop him to ask about the red Corvette he drove here in. “Yes.” he says, understanding what I’m asking him. He tells me he bought it after finding a toy model of Lightning McQueen, the red car from the Pixar movie Cars, on his bed. It was a sign. It was unitary consciousness.

“Anyway, I was tripping out because our family was trying to be a unit, and I’m saying, ‘We need to plug in with each other. Let’s have dinner, plug in and feel each other.’” As he said this, he recalls, Homer Simpson repeated the same thing on the TV. He glanced over, and saw the Simpsons falling from a plane, trying to “plug in” and extract power from one another and cushion the fall.

At this moment, Jason felt like he was holding an umbilical cord to the divine. He was Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole, Peter Pan flying straight through to morning from the second star to the right, Lucy crawling through the wardrobe.

“My mentor says I don’t need to share this with anyone because it’ll only make me seem more crazy,” he says. “I can definitely see it being a paragraph where it’s like, ‘He think he’s God.’” It’s one of several times Jason references this article, worried that he can see his own story forming in my mind.

“Oh, and by the way, I met God, and she’s Black,” Jason adds.

Jason, to be sure, does not consider himself God. In his view, he’s closer to a prophet, a divine mystic; someone who spends their life trying to communicate what exactly God is, channeling her love like a river.

He reads me a centuries-old poem by the mystic poet Hafiz from his phone.

“Running/Through the streets/Screaming,” he reads, enunciating each word as though they have the power to split the world apart. “Pulling out my hair/Tearing off my clothes/Tying everything I own/To a stick/And setting it on/Fire.”

He looks up at me to make sure I register the connection.

“What else can Hafiz do tonight/To celebrate the madness/The joy/Of seeing God/Everywhere!”

He puts his phone away, blood rushes to his cheeks, he appears flushed with some kind of divine aliveness — it doesn’t last. He looks at his feet on the ground.

“That is my life. I ran through the streets, I tore off my clothes. I played with fire and I saw God everywhere,” he says. “But then you come out of it, and you’ve done damage. There’s like actual collateral damage.” Even divinity, it seems, has dire consequences.

“I wish I could tap into the consciousness all the time every day, but it’s just not possible,” he adds. “It doesn’t last forever, but it can return. And I think if it does return, it’s my job to make sure it’s under a very tight leash.”

Ten days after the video’s release, Jason tells me he had a divine encounter with the Holy Spirit. While a pastor read Psalm 46 (“The God of Jacob is our refuge”), he fell to his knees and began to cry on the church floor. He felt a spirit move through him. “God, how are you doing this?” he asked.

Jason experienced auditory hallucinations for the first and only time in his life three days later. This is the first time he’s told this part of the story.

“Those that have tried for world peace have had to pass this test,” the voice said. “You can be Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela.”

“OK, whatever it takes,” Jason said to the voice. In that second, he felt a heavy sensation in his head which soon spread to the rest of his body. He became weightless, gravity escaping him. He felt like a marionette, strings pulled by some unknown force. Time sped up. Time slowed down. Timshel left his body. Fate became him. He took to the streets, wearing only underwear and a bathrobe, which he soon removed. He pounded his fists on the hot pavement. He shouted. He cursed. A passerby caught him on camera, selling the footage to TMZ for $30,000, according to Jason.

Back in the Invisible Children offices, the communications department had been restlessly checking articles and online criticisms of Kony 2012 for the past week and a half. On the morning of March 16, they saw a headline indicating that Jason had been masturbating in the street (a TMZ exaggeration — Jason is naked in the video, but is not masturbating). “Look at this,” Krista told a fellow staff writer, believing it was cheap gossip, clickbait. Together, they read the TMZ article, scrolling down to find the footage of Jason on the streets at the bottom of the page. “This I’ll never forget,” Krista says. “My fellow writer fell to her knees, fell to the ground. Legs collapsed. It was absolutely unreal.”

Krista then gathered all 10 of the interns together, flocking them into her office. “We didn’t want them to see it, as if we could keep it from them forever.” From her office, she texted Jason’s sister. “Tell me this is not happening,” she said. “Not in the way they’re saying it is,” Janie responded.

As the Invisible Children G-Chat was exploding with messages from confused, exasperated staff, Ben Keesey, the CEO — who was hired by Jason and fellow founders Laren and Bobby — immediately called an all-hands-on meeting. He told them everything he knew: Jason had fallen ill, he had taken to the streets, a passerby captured him on camera, he had been hospitalized. After confirming the news, almost everybody in the office began to cry. They experienced utter devastation. They understood immediately that their several months’ worth of work had now been for nothing. “It was heartbreaking, nauseating,” Krista says.

For 36 hours, Invisible Children went dark. “Not because we weren’t going to deal with the aftermath, but because we had to protect our own selves, else we would all become Jason,” Krista says. Everyone went home. Krista slept for 14 hours. When she woke, she believed she was still dreaming.

When the staff returned to the office, Tiffany Keesey, the CEO’s wife and HR manager, had yoga professionals and therapists come in while everyone else was making a list of words to block from the Invisible Children social media accounts. The most common word — and one that most of the staff had never come across before — was “fap.” “Apparently it’s the sound of masturbation,” Krista says. “We were drowning in ‘fap.’”

Despite sold-out screenings across the nation, there was talk of bringing the roadies home. “Things were bad in the office, but I can’t even imagine what the roadies were going through,” Krista says.

Saul and his team were right outside of Chicago when they heard the news. They pulled into a McDonald’s parking lot when they received an email from the Invisible Children’s offices: “Standby, you’re about to receive a call from your regional manager.”

Jess — the person responsible for overseeing the Midwest team — called shortly. “We thought, ‘Oh shit, we’re going to have to spend the next several weeks talking about this, not about the programs or how to write letters to senators or the Invisible Children finances, this,’” Saul says. The team sat down in the parking lot and briefly scattered to have some time in private. Saul called his dad. “I think it’s all over,” he told him. Instead, the team came back together, and stayed on the road. They made it through those scheduled screenings, but it was a major comedown. “It wasn’t the following several weeks that were the toughest,” Saul says. “It was the summer after we got off the road, when I was alone.”

On April 20th, “Cover The Night” — an initiative that was supposed to mobilize the crowds swayed by Kony 2012 away from their screens and onto the streets, where they’d paste posters of Kony all over buildings, lampposts and shop windows — inspired a paltry turnout. The few posters that were spread were quickly swept up by street cleaners come morning.

Jason was ultimately hospitalized for several weeks. A statement by his family at the time said the diagnosis was a “brief reactive psychosis, an acute state brought on by extreme exhaustion, stress and dehydration.”

In December 2012 — nine months after the video’s release — the Invisible Children staff lit a bonfire in the office parking lot. The leadership had been talking about a tradition among rescued L.R.A. soldiers, how, when they returned home, they’d burn the clothes they’d been abducted in. They suggested trying something similar. Leadership had everyone write down something they had been struggling with. They threw their pieces of paper into the fire, and thought about healing.

“I will always be grateful to Invisible Children. … Hard as it was sometimes, [it] kind of shaped me into who I am today, and I’m always gonna be grateful for that,” Saul says. It’s a shared sentiment among everyone I spoke to (though, out of the dozens of former staff and roadies I reached out to, most didn’t reply). “It’s PTSD,” Jason explains. “Most people don’t want to talk.”

In late 2014, Invisible Children underwent a significant restructuring and downsizing. Lisa Dougan, who had worked with the company across the Kony 2012 campaign, replaced Ben Keesey as CEO. In 2015, they prepared to shut down. “We worked with our Central African staff and local partners to prepare for a closure,” Lisa says. The funding spigot had been turned off, not only for Invisible Children, but she also “witnessed almost every other international organization supporting L.R.A.-affected communities shut down their operations due to lack of funding,” Lisa tells me. “In D.R.C., the number of international organizations working in L.R.A.-affected areas dropped from 19 to 2, one of which was Invisible Children.”

With L.R.A. violence still ongoing at that time, Invisible Children decided instead to remain open, installing a transition team that was led by Lisa, who mapped out a strategy to help sustain Invisible Children’s work in Central Africa. Between 2015 and 2016, they obtained a number of grants that would permit them to maintain a smaller-scale operation. In 2017, they secured a five-year partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development, allowing them to significantly expand their program.

“As a woman of color now leading Invisible Children, I am thankful for the public conversations triggered by the Kony 2012 campaign about white saviorism and about whose perspectives are centered in storytelling,” Lisa says. “And thanks largely to the work of BIPOC women activists and organizers, these conversations and demands for concrete action to address white saviorism and other forms of structural white supremacy have advanced so much further over the last 10 years.”

Creative storytelling continues to play an integral role in Invisible Children’s strategy, “but we use it quite differently now and in a way that I believe further embodies our values,” Lisa says. “Since 2013, we have been producing films by, with and for central Africans rather than for a U.S. or international audience.”

Jason stayed on with Invisible Children until December 2014. A month after departing, he founded a new creative agency, Broomstick Engine, which, in its eight years of operation, has strategized and launched campaigns for the likes of Toms Shoes and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Jason no longer has any involvement with Invisible Children. “My job now is to basically make white savior movies for organizations,” he tells me.

In 2017, Jason released his Kickstarter-funded book A Little Radical: The ABC’s Of Activism, co-authored with wife Danica. It’s a children’s book breaking down the fundamentals of humanitarian advocacy, featuring photos of their own children. Today, he works on a freelance basis, collaborating with numerous clients on script production, post-production and animation. He still appears to be friends with many people in Hollywood; this year, he watched the Oscars (his favorite event of the year) with singer-songwriter Lorde. He does yoga. While he used to work all through the night, today he sticks to a stricter routine, going to bed no later than 10:30 p.m.

He still thinks about Joseph Kony and the children of Uganda. “Every day I find it hard to believe Kony has not been captured,” Jason tells me — though for now, his sights are set somewhere else, toward gun reform in America.

He sits up in his seat and begins something like a pitch. “So, my idea is controversial. My idea is too big to imagine, but I still want to try it because I think it has to be so disruptive and so strong that people can’t dismiss it.”

Step one: Make a viral video. “But I’m not in it, it will be a child talking to the screen: ‘Please help, we need you.’”

Step two: Meet up in spaces across America that have been subject to mass shootings: concerts, movie theaters, schools, churches, synagogues.

Step three: Pick a route and march from your chosen building to the freeway, and spread out. If a car tries to get past, you will be blocked, or you’ll have to run us over with your car, “which hopefully no one will do.”

Jason already has a name for the campaign: Do Nothing.

“You thought that the pandemic made you do nothing? No. How about you can’t get on the freeway? Then you’ll do nothing. Will we have routes for ambulances? Probably. Will we have a physical barricade [preventing cars from getting on and off]? Probably. Will Lady Gaga do a concert on the 405? Absolutely. It’s going to be historic, it’s going to feel like the French Revolution.”

This all sounds familiar, I tell him. He smiles at me when I say part of me worries for him. Where does creativity end and madness begin? Where does God stop and mania start? If they exist on the same thread, then it’s a tightrope Jason will have to tread carefully.

Just over a decade after attempting to alter the course of human history, Jason Russell is still determined to shape humanity’s story. Only, now that he’s in his mid-40s, on the other side of a major breakdown, the fire in his eyes has dulled to a calm flame — he’s no longer willing to lose sleep over it. This may not be the story of a boy who saved the world, but rather the story of a boy who was forced to grow up.

Emma Madden is a journalist primarily based in Brighton, England. They have written for the New York Times, GQ, The Guardian, among others.

Brendan Spiegel is the Editorial Director and Co-Founder of Narratively.

Yunuen Bonaparte is Narratively’s Photo Editor.