The (Literally) Unbelievable Story of the Original Fake News Network

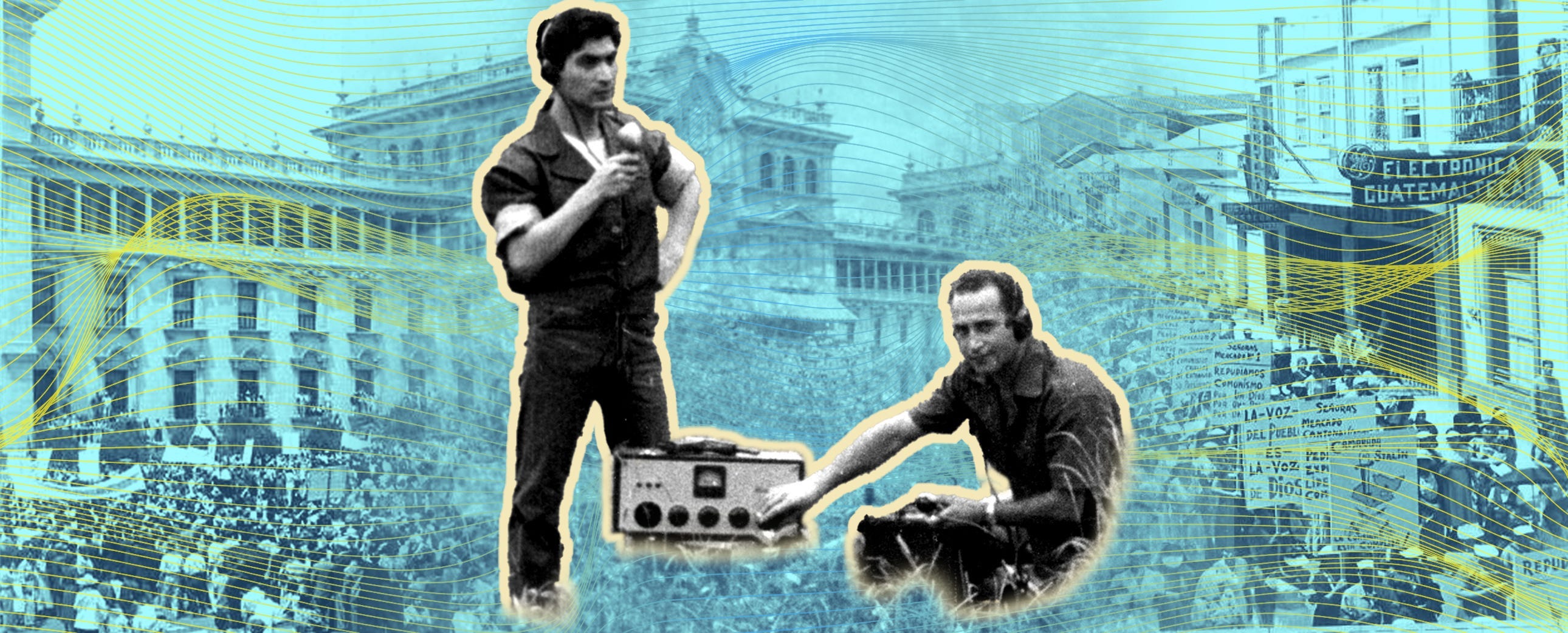

Once upon a time in Guatemala, the CIA hired a cocky American actor and two radio DJs to launch a revolution and oust a president. Their playbook is being used against the U.S. right now.

Guatemala City looked like a ghost town.

The capital’s 450,000 residents hid in panicked self-quarantine, waiting for the first wave to arrive. World War I–style military planes periodically flew overhead, firing warning shots and dropping leaflets telling people to either flee or stay indoors.

A civil war was moving toward them.

All week, Guatemalan radio had been blasting the news of gruesome battles around the country. The newspapers were going crazy. Two Americans in a tourist plane had been shot down by Guatemala’s Communist army. Refugees were fleeing to Mexico while 400 injured Communist troops were retreating to the capital for medical treatment.

Now, on Saturday morning — June 26, 1954 — radio news broadcasts reported that two columns of anti-Communist patriots calling themselves the “Liberation Army” were 60 kilometers from the capital. And marching fast.

All vehicles were now military targets, the radio warned, so citizens should stay out of their cars. Trains had been stopped due to the intense air battle raging in the northeast. And a sabotage unit of the Liberation Army had just received orders to blow up a bridge in “Sector H-21.”

Soldiers from the Communist government’s own military were now defecting in droves, newscasters reported. Five hundred and thirty-eight civilians had joined the Liberation Army just yesterday.

In response, the government had suspended the constitution. The president had ordered all anti-Communists found on the streets to be rounded up.

The whole world was watching this catastrophe unfold, the radiomen reported.

At 11 p.m., the broadcasters read aloud a message issued by the Guatemalan chief of police:

To all Department Governors in the Republic. Capture immediately all mayors and other anti-Communist city officials currently affiliated with parties of the revolution. … Keep them in prison, and at the first shot fired when you are attacked, shoot them immediately.

All weekend long, the radio newscasters implored government soldiers to stand down. Remaining at one’s post would only result in needless bloodshed, the newscasters warned. The only way to end the carnage was to abandon the president, who “preferred suicide to surrender.”

Guatemala’s 41-year-old president, Colonel Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, was not known for his sense of humor. But if there was anything that had the chance of making him smile that day, it might have been this last claim. Anyone who knew Jacobo Árbenz knew he would never say something like that.

But he was not laughing, because what he knew was more infuriating than humorous.

There was, in fact, no real “Liberation Army.” Just a few dozen pissed-off exiles hiding out 6 miles in from the border of Honduras, staging strategic photos for the press, like a bunch of 1950s-era Instagram influencers holding donated rifles. The “invasion” was more smoke than bombs.

No refugees or injured soldiers had fled anywhere. The chief of police had not issued orders to round up anti-Communists. The two Americans in that “tourist” plane were actually the ones dropping leaflets, contract pilots. They hadn’t been shot down; they’d run out of gas and been captured by authorities in Mexico.

There was no civil war about to engulf the capital, and most ironic of all: Guatemala was not a Communist state. President Árbenz was a political independent, having run as a moderate — and certainly was not a Communist. And though the country did have a small Communist Party and four representatives in Guatemala’s 56-member congress, not one Communist held a cabinet position in Árbenz’s administration. The president considered himself friends with two Communist Party leaders, but he was also friends with right-wing leaders. His own chief of armed forces and handpicked presidential successor was a conservative. Árbenz was a cool-headed military man like his counterpart President Eisenhower. True, in his ideal world, Árbenz would have Guatemala look like the USA under FDR. But he was a pragmatist. In the United States today, his policies would have been closer to those of Bill Clinton than Bernie Sanders.

And that radio station everyone was reacting to? It wasn’t even in Guatemala. The disc jockeys aired their “reports” from a shack in Nicaragua. Many of their broadcasts had actually been prerecorded earlier in the year.

In Florida.

In an office belonging to the Central Intelligence Agency.