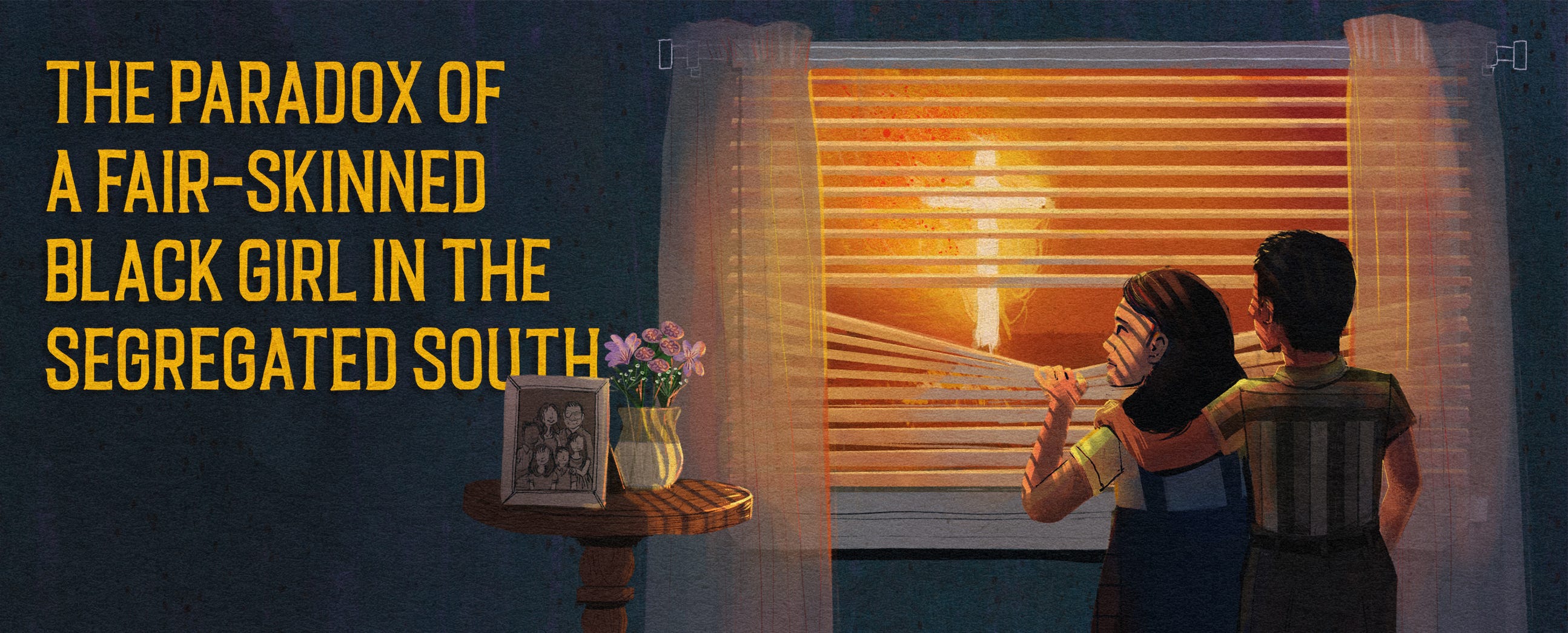

The Paradox of a Fair-Skinned Black Girl in the Segregated South

Wylene felt safe despite the burning cross on her lawn and the subtler affronts that colored her Arkansas childhood. She never expected her deepest trauma to be inflicted by someone of her own race.

We’re so happy to be presenting Wylene’s story to you today, one of the two finalists from our 2023 Memoir Prize, a beautiful piece about perception and the things we carry with us that makes us tear up every single time we read it. Wylene on writing it: “I have written pieces of my memoir over many years. In these reflections, I have learned so much about my parents and myself — understandings that could only come with age, wisdom and greater objectivity. I am grateful to be a finalist in the Narratively memoir competition. I feel uncomfortably exposed — but also appreciated, and I hope my story has meaning for others.”

It was September 1957. The sun was hidden by the evening sky, but it was too early for bedtime. So, I sat on the blue plush carpet in my parents’ bedroom at the front of our house, leaning against the wall by the door. While sitting with a Nancy Drew mystery, I had a full view of my mother, who lay in bed, weak and ailing, having just come home from Davis Hospital’s maternity ward in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where we lived. She came home without her baby, my youngest sibling, Debbie, who had been born much too soon. At 4 pounds 4 ounces, she was still fighting for her life in a hospital incubator.

I don’t think I was accustomed to reading in my parents’ bedroom and imagine that I was keeping an eye on my mother, who had been hospitalized and away from us for several days. I guess I was making sure she was OK and glad to have her home, although I would not have said that to her then. I was 7 1/2 and must have felt relieved to have her back, safe, alive, since I have a vague memory of my father gathering us five older children and telling us in a hoarse voice that Mother was very, very sick and she might not be able to come home.

This night, Daddy was probably on his way home from Little Rock, where he was helping nine Black teenagers who were trying to integrate Central High School there. That’s how he described his work to us, by telling us what he was trying to do. I understood later that he was in fact the chief counsel in the Arkansas school desegregation case. He had called Mother, as he always did, when he was starting out on the highway to come home. For many years, I thought those phone calls before he set out on the road were so Mother would be able to have dinner hot and ready for him when he got home, or so she had time to take the curlers from her hair and pretty up for him. It was not until I grew up, however, that I realized those calls were safety measures. This work was dangerous, and if he did not return home by a certain time, Mother would know to send out a search party to make sure he had not been run off the road, kidnapped or worse by people who did not want him helping to integrate Central High.

My brothers and sisters were playing in their rooms or getting ready for bed and being extra quiet to give Mother some peace when, suddenly, my 11-year-old brother, Ricky, ran to Mother’s bedside.

“Mother, Mother,” he shrieked. “There’s a cross burning in the front yard!”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.