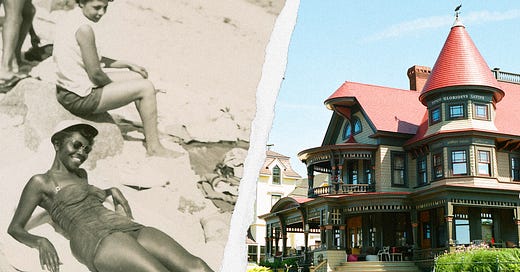

The Real Story of Black Martha’s Vineyard

Beyond the beautiful beaches and glitzy galas, Oak Bluffs is a complex community that elite families, working-class locals and social-climbing summerers all claim as their own.

During a weekend in which we’re immersing ourselves in all things Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., one anecdote we love is that in the 1960s, King used to frequent Overton House, a Victorian mansion in Oak Bluffs, the town in which this story is centered. The house was nicknamed the “Summer White House of the Civil Rights Movement” because of the many prominent Black leaders who spent time there, and King is said to have done a lot of his work there. Revisiting this Narratively Classic transported us to an Oak Bluffs of yesteryear where we like to imagine we might have bumped into King at Overton and shared a smile. —Narratively

Elizabeth Gates was 12 the first time she snuck out of her family’s summer house. From the balcony of their white antebellum home, Gates could hear Biggie rap lyrics pulsing through her window, and she quietly made her way down to the beach where a mass of people were dancing in the thick, steamy air. That was how so many summers played out until Gates turned 16, when she no longer had a curfew and could finally stay out all night reveling in the beach parties and bonfires that drew heavy crowds to Oak Bluffs, a quaint town on the northeastern shore of Martha’s Vineyard, a 96-square-mile island shaped like a shark’s tooth off the coast of Massachusetts.

“It was this hub of relaxation, and a marker for all my rites of passage,” says Gates, a writer and the daughter of public intellectual and African-American scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. In the past, Oak Bluffs has been hailed as a summer playground for the elite, but that neat summary doesn’t tell the full story, as interviews with close to a dozen summertime vacationers and longtime residents recently showed. As in any place with a treasured history, powerful personalities, breathtaking vistas and scarce acreage, there is tension: between longtime residents and newcomers, between year-rounders and those who summer, between old and new. And always, there is the fear that as this cherished community continues to evolve, it will lose the very things that make it so special.

Oak Bluffs became a tourist destination out of necessity. Named for its scenic perch in an oak grove overlooking the Nantucket Sound, in the Atlantic Ocean, it was a haven for African-Americans during the mid-20th century when Jim Crow laws and segregation meant that Black vacationers were often turned away from mainstream beaches and hotels. Oak Bluffs was the only town of the now six on Martha’s Vineyard where African-Americans were permitted to find lodging. Initially, freed slaves sought shelter there after slavery was abolished in the mid-19th century. Many worked in the fishing and whaling industry. Then, in the 1930s and ’40s, as African-Americans in urban centers like New York, Washington, D.C. and Boston began to take up jobs in professional industries and establish themselves as part of the middle and upper-middle class, they flocked to the East Coast shoreline in the summer to take in the beach and the bonfires. Today, Oak Bluffs, which sits on 7.4 square miles of land, maintains the charm of a fishing village with its colorful gingerbread cottages, pristine beaches, bustling marina and old-time seafood joints.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.