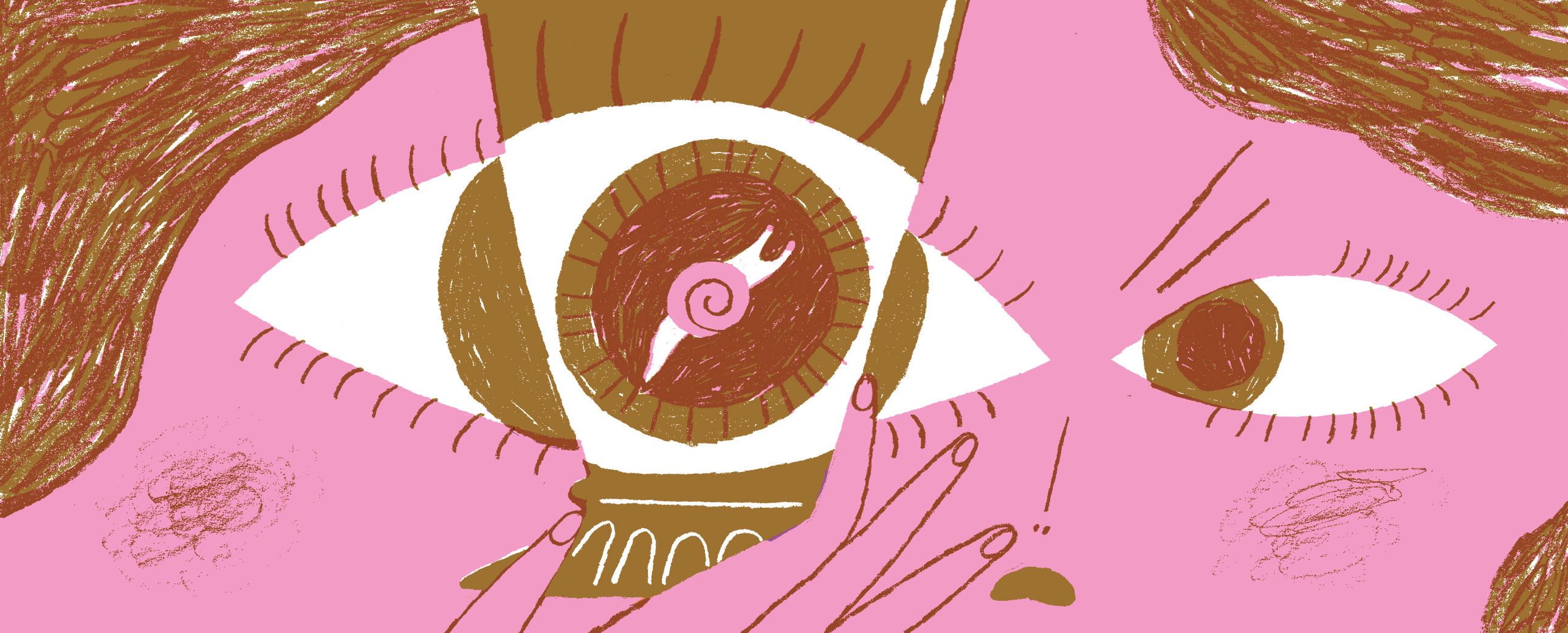

The Woman Who Found a Snail in Her Soda and Launched a Million Lawsuits

Sixty-six years before the infamous spilled McDonald’s coffee, May Donoghue drank a ginger beer with a dead mollusk in it and changed personal-injury law forever.

May Donoghue was not the weak-natured type.

Growing up with little and losing three babies in their infancy, Donoghue had overcome a lifetime’s worth of hardships by the time she was 30. But she was not prepared for the snail.

Donoghue spied the decomposing gastropod, mixed with bits of ice cream, bobbing in a glass of ginger beer that she had been sipping at the Wellmeadow Café in Paisley, a small Scottish town not far from where she grew up. The sight of it would continue to haunt the Scottish woman for years to come.

When Donoghue and her friend complained about the snail to Wellmeadow Café owner Francis Minghella, they received barely a shrug and “well, it happens” in response. Donoghue wrote down the name of the ginger beer producer — Stevenson — and left.

Three days after finding bits of dead mollusk in her drink, Donoghue visited a doctor for sharp pains shooting in her stomach.

Three weeks later, she was hospitalized at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary with severe gastroenteritis and shock.

Donoghue’s next steps — seeking out a lawyer and filing a claim against both Minghella and David Stevenson, the owner of the company that made the ginger beer — were not exactly typical for people of her background. Lawyers were for wealthy people. Donoghue, the daughter of a steelworker, was the second youngest of six and worked as a shop assistant.

Had it happened today, the incident would have made national news and likely earned Donoghue a large compensation check. But she found the snail on August 26, 1928 — long before high-profile personal-injury lawsuits against companies like McDonald’s and Ford were the norm rather than the exception.

Most Scottish lawyers of the day would have told Donoghue that she did not have a fighting chance of winning the suit. Personal-injury laws only applied to the person who had purchased the defective product, and it was Donoghue’s friend, not her, who had paid for the ginger beer. The only exceptions were if the product was inherently dangerous or if the producer had misled the customer into thinking it was safe while knowing that it wasn’t. In either case, the ginger beer did not qualify.

But as it happened, Donoghue came across a solicitor, Walter Leechman, who had worked on but lost several similar cases, and he agreed to help her fight the law. To him, it was a matter of principle — Leechman agreed to represent Donoghue pro bono.

After nearly a year of preparing documents and going through legal books, Leechman and Donoghue filed a lawsuit asking for £500 in damages and £50 in court fees. The sum, worth approximately £35,000 ($45,000) in today’s money, was considered extravagantly large.

As with many personal-injury cases today, the matter became about much more than the incident itself — and it came at great personal cost to Donoghue.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.