Our Therapist Gave My Wife and Me MDMA—and It Saved Our Marriage

Julianna and I were on the brink of breaking up when we were met with an unexpected proposal that changed the way we saw ourselves and each other, forever.

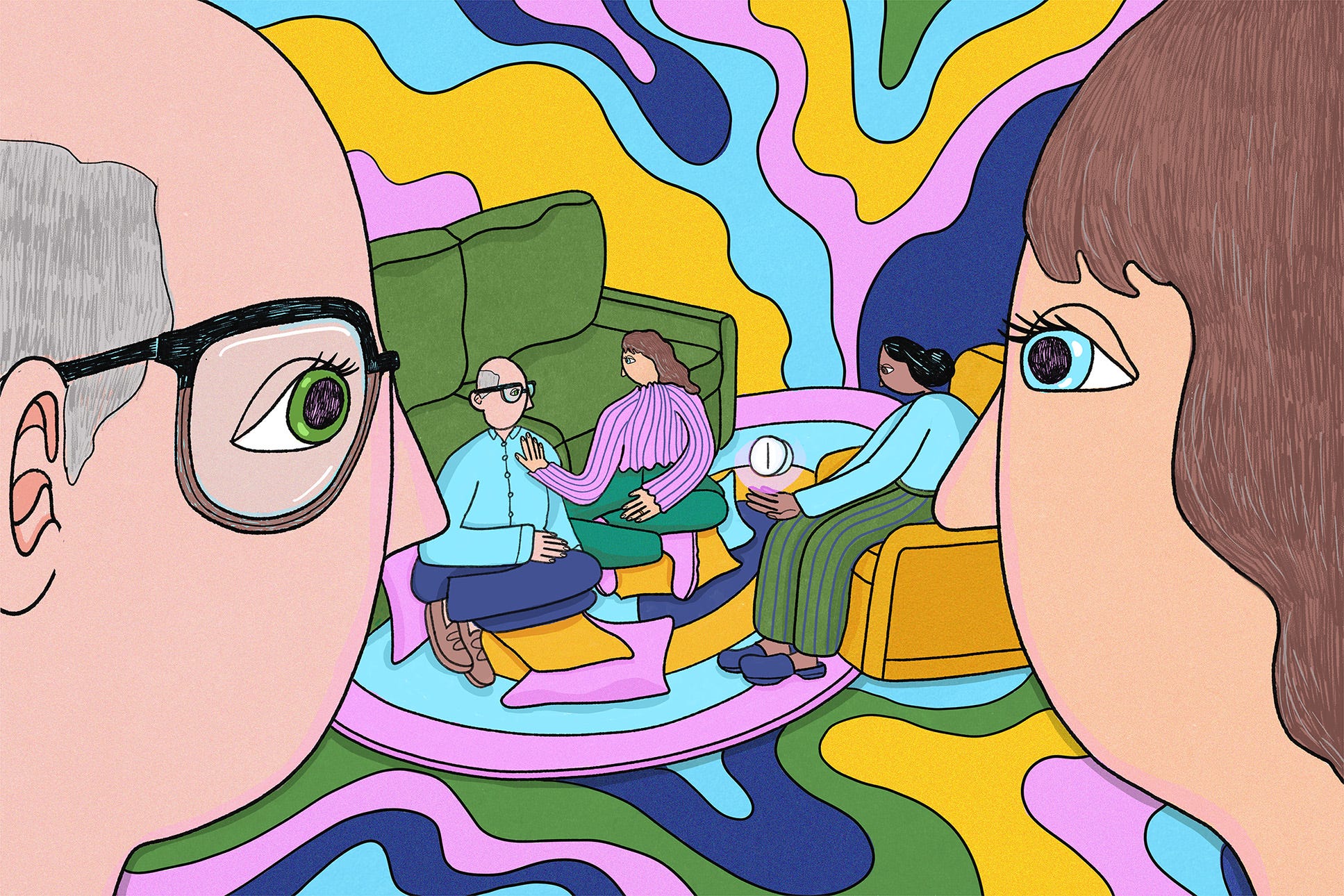

When I excitedly shared this story at a team meeting a few months back, my colleagues heard the keywords in my spiel: a struggling couple, midlife crisis, on the verge of divorce … and did not see the second half of my pitch coming: the part about Seth taking drugs with his wife on the recommendation — and in the presence — of their therapist! It was decided then that this would become the second piece in our series collab with Creative Nonfiction, Heart of the Matter. What follows is not an excerpt exactly, but a piece with some overlap from a short section of Seth’s book, Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir. And if this new, amazing story weren’t exciting enough, we’re also thrilled to share an original, custom audio version of this story. So, click above to hear this essay read out loud by none other than the author, Seth Lorinczi himself, and then make sure you follow our podcast, Narratively Out Loud, in Spotify, Apple, or your fave podcast player, to tune into future episodes. Thank you for reading and listening!

—Jesse Sposato, executive editor

I stared down at the little capsule in my hand. It didn’t look particularly special, but then again I didn’t know what MDMA was supposed to look like. Was it “good” MDMA? Was there an organic option? These were stupid questions and I knew it, but I was trying to distract myself. I glanced over at our therapist, Renee, but she was busy lighting candles and incense. I looked at my wife, Julianna, but she didn’t have any better ideas than me. What did it matter, anyway? The way things were going, we were probably getting divorced, not dancing with glowsticks all night.

Taking MDMA was Renee’s idea. I didn’t know that providing drugs was a service she offered, or if it was even legal (it wasn’t — and Renee’s not her real name; I’ve changed it for privacy reasons). But we’d already ground through a couple of sessions trying to figure out how to save our marriage and gotten nowhere. When she casually suggested trying a session under the influence of the drug, I was taken aback. Was getting high really going to change anything? But I’ll admit I was intrigued.

Julianna and I had met nearly two decades before, in the Bay Area punk scene when we were still in our 20s — she was a drummer and I played bass. She was a natural: pounding her kit with a ferocity that belied her shyness and slender build. And when she finally worked up the courage to open her mouth and sing, it was all over: She was luminous, striking, transfixing. Soon it became obvious that we belonged together. A couple years after she moved in, we pulled up stakes and relocated to Portland, Oregon.

Portland was a revelation after the grind of San Francisco. We could afford to buy a beautiful house and build a recording studio in the basement. We released an album under the name Golden Bears, and people started to take notice. Someone referred to us as a “power couple,” and I felt like it. We were going to do great things together, she and I. In addition to playing music, Julianna began to pursue a fine arts career, and a few years later, we decided we were ready to give parenthood a go. Julianna gave birth to our only child: a feisty spitfire of a daughter. As far as the rest of the world was concerned, we’d made it.

In hindsight, of course, I could see the glaring holes. No one came to the punk scene without some sort of trauma, and from the barrenness of Julianna’s Christian fundamentalist upbringing to my own mother’s death when I was 4, we’d each brought our baggage into the relationship. I was defensive and unable to resist deploying my own father’s authoritarian parenting style — even though I hated the way it made me feel. Julianna had her own struggles, contending with a nagging sense that she was only needed when she was being of service to others.

But while Julianna found release in her singing and her astonishing paintings, I hid my emotions. I put my energy into writing and recording music, spending hours grinding away in my basement studio. If I wasn’t working, I felt I was wasting my time. All the while, I thought I was doing Julianna a favor by keeping my sadness under wraps, but stuff has a way of coming out sideways. As the band started gathering steam, I only grew more anxious and controlling. If music set Julianna free, I experienced it as a source of stress. This was our only chance, and we had to get it right!

We kept playing, released a second album, set our sights on bigger stages — but my discontent followed us. Even though Julianna was caught in the grip of an autoimmune disorder, drumming like a demon through the pain, I insisted we push harder, play more shows so that we could sell the records piling up in the basement. Driving home one night after a seven-night run of undersold shows, sitting wedged beneath a snare drum and a case of unsold records, Julianna burst into tears. “I can’t do this anymore, baby,” she sobbed. “I can’t go on like this.” She quit our band. Music was our love language, the place we found the most natural intimacy. With that gone, who were we to each other?

From there, things really began to fray. Julianna wanted to sell our house and move. It was too big and too cold for a family of three; plus, a smaller home would make better use of our limited resources. But that was totally out of the question for me. I’d spent years building the perfect basement studio; I couldn’t just leave it behind. Still, she wouldn’t let up, asking me to at least consider it. I could hear the desperation in her voice, but I wouldn’t budge. For my part, all I could think to do was push her to market her paintings so we could bring in more income. Needless to say, that didn’t land well either.

Late one night, after we’d put our daughter to sleep, Julianna and I met in our bedroom. We’d been needing to talk about our finances for weeks, though it always seemed to get postponed. Now I felt a familiar apprehension stirring as I sat down at the foot of the bed.

“How was your day?” Julianna asked.

“Eh, not great. I made some progress on this recording job, but it doesn’t sound that good. I can feel myself grinding.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” she said. “You’ll figure it out.”

“What about you? What’s going on with your work?”

“I’m still working on that commission,” Julianna said, “and another’s coming in next month. But it’s hard to focus on anything when I feel so awful all the time. I got some results back from the naturopath and it looks like I have to follow this stupid diet where I can only eat like three things.”

“I know, and I’m sorry, but … you could do even more with all your talent.”

“Look, my body’s in real trouble,” she said. “And you act like we’re going to be evicted tomorrow. That’s not what’s happening. You seem so afraid all the time. There’s no wolf at the door; we’re safe. And I need to get better, and I’m going to get better, but not with you pacing this house like you’re about to walk the plank!”

At this I finally boiled over. “We’ve got nothing!” I said, louder than I’d intended. “The roof is falling in and we don’t know what the fuck we’re doing with our lives. Why can’t you see that?”

Julianna got up and stormed downstairs. After a moment of teeth-clenching rage, I followed her. I found her sitting on the kitchen floor, her head resting on her knees. She was feeling around as if she were blind, touching the faces of the built-in cabinets, the wooden planking of the floor. I found it unsettling, and I glared at her, toggling between anger and fright.

“I know this is all so fucking real,” she said. “I know this is so important, that we have to do all the things, we have to be good parents and make money and think about our retirement. But sometimes I just want to meet you outside of the story. I want to pop our heads above the big fucking story and just be for a minute.”

I fixed her with a look of utter contempt: “I don’t understand what you’re even talking about,” I half shouted. At this Julianna curled on her side and began to wail like an animal. Fed up, I turned and left for the basement.

I looked around in the cool silence. Down here, everything seemed so right: the gleaming metal of old preamps, the deco knobs of vintage equalizers. But why didn’t they give me any comfort? I wondered how long Julianna and I would go without speaking this time around, how we’d manage to disguise the icy silence around our daughter. These conflicts seemed to flare up every other week; it surely wouldn’t be long before she started to notice.

It was Julianna who blinked first. A few nights later, she sat me down on the edge of our bed. “This isn’t working,” she said. “I’m going to call that therapist I got a referral for. We have to find a different way, or we need to step away from each other gracefully.”

I felt exhausted, sad. And I felt helpless, a bug pinned on flypaper.

“OK,” I said, utterly resigned. All I wanted was for this pain to go away.

Hence Renee, the drug-dealing therapist. She seemed good enough at her job, based on the couple of sessions we’d had, but it hardly mattered. The truth, I thought, was that I was probably meant to be alone, and no amount of therapy was going to change that. I was an idiot for having even tried to have a normal relationship and family.

Had Julianna and I ever really been in love? I honestly didn’t know anymore. And anyway, we definitely weren’t now. What difference would taking MDMA make? Still, we set a date to give it a try in two weeks’ time.

The whole of that long, silent drive to Renee’s office, I felt like I was headed to my own execution. As we walked upstairs, shoes clanking on the metal staircase, I felt suffused with fear that I was going to see and feel things I might not be ready for. But there was something else, too: a glimmer of curiosity. Maybe, just maybe, we were being offered a second chance.

The room we’d known only in daylight had been transformed. The walls were lit by candlelight. Nests of blankets and pillows beckoned us to the floor, not the couch. I sat down and made myself comfortable, as much as my thumping heart would allow. Renee had transformed as well. In daylight, she exuded a blend of warmth and incisiveness. Now the precision of her clinical persona had given over to a witchy energy. I felt both excitement and unease. If nothing else, we were somewhere — anywhere — besides our dark house, circling each other like prisoners.

Renee sat down with us and produced two tiny baggies. Inside each were two capsules, one to take now and one to have in a couple of hours. I looked at Julianna. Though she had even less drug experience than I did, she didn't look scared at all. In fact, there was a welcoming softness in her eyes, a tiny glimpse of the kindness that first drew me to her, 17 years earlier. I looked at her and said, “This is really it,” or something equally stupid, not even knowing what I meant. The end? The beginning?

Satisfied with her ministrations, Renee turned back to us with a warm smile. “It’s time to begin,” she said, then offered up a tiny prayer: “Deepest knowing, deepest healing, deepest medicine.” Julianna and I stared each other squarely in the eyes, and then we swallowed our pills.

For what seemed like a very long time, nothing happened. We lay on our nests of blankets and pillows. After 20 minutes of silence, I began to wonder, with a mix of disappointment and relief, if the medicine just wasn’t going to work.

The clock dripped on. Because my bladder has the capacity of a single-shot espresso cup, I got up and padded to the bathroom. A few minutes later, I did it again. This time, I noticed the floor had tilted slightly. My joints felt pleasingly loose, and the ambient temperature had risen a few degrees. I realized I probably shouldn’t be upright much longer.

When I returned to Renee’s office, Julianna was shaking: Lying beneath a blanket, her whole body was twitching and jerking. I felt a brief stab of fear: Something had gone wrong. But Renee turned and sent a comforting look my way, assuring me that this was in fact normal.

Back in my nest, I watched the last glimmers of daylight play against the wall. I was fully caught in the pull of the medicine — Renee never once called it a “drug” — and I liked it. A lot. Everything felt slowed down and gentle. I drifted into some new and warm place, fear dropping away like molted feathers. But I wasn’t leaving my body; I was entering it for the first time. I felt a deep, full-body safety; the grating fear I’d felt an hour ago had vanished. I blinked my eyes open, stunned by the soft grace of this medicine. Anything felt possible.

The storm passing through Julianna’s body lifted. She stirred in her blanketed nest, then sleepily pulled herself upright. Although she’s already a physically beautiful woman, something extra shone through her then, a radiance illuminating the fine lines of her face and those wondrous, bottomless blue eyes. She looked at me and said with quiet and total clarity: “I don’t want to get a divorce.”

When I’d stepped into Renee’s office that evening, I wasn’t exactly a stranger to psychedelics. I’d taken a lot of LSD as a teenager, and even during the speediest, most jaw-clenching trips, I’d found it strangely calming. For a few precious hours, my anxiety would recede; I’d feel like I belonged here on earth. Right now, in Renee’s office-nest, I felt that same sense, only magnified a thousandfold. I wasn’t high. I wasn’t entranced by trippy visuals. I was just … there. And as the impact of Julianna’s words took hold, I felt totally overcome by awe.

I stared back at her. Her skin was luminous and flushed, her hair tousled — was this the medicine, or did she really look this beautiful? — and I saw how badly I’d needed this lifeline. The truth was that I was desperate not to lose her, but this whole time I’d been so closed off it was hard to see what was right in front of me. Here was this wondrous person telling me she loved and wanted me, and I’d never even thought to say: “I love you too, but maybe I don’t know how.”

I smiled back at her. “OK.”

This whole time, nothing “happened,” per se. We were just three people sitting in a room somewhere in downtown Portland. And yet normal life was millions of miles away. I’d learn, later, that MDMA is sometimes called an empathogen, meaning it fosters unspoken understanding and compassion. Here’s what I did know in that moment: My entire identity suddenly felt up for review. The quiet fears that had haunted me my entire life — that the world didn’t care about me, that everything I did ended in failure — those were just stories I’d told myself. And now everything, from how I related to Julianna to how I navigated the world from behind thick armored glass, was starting to go out the window.

Renee sat quietly at the other end of the room, watching with an expression so serene that I wondered if she’d taken the drug herself (I didn’t ask). Now, sensing that something had turned a corner, she finally spoke: “You both are doing such good work here. Allow the medicine to soften you even further; you’re right where you need to be.” She turned to face me. “Seth, I’d like to ask you to try laying down for a little while.”

As I made myself cozy in my nest, Julianna rose and, unbidden, gently placed her hand over my heart. I closed my eyes, and as I did a movie began to unreel behind them. It took me a moment before I registered that it was a distant memory tumbling forth: the night my mother went to the hospital and never came back.

It was September, 1975. I was 4 and a half, sitting in my flannel pajamas on the staircase leading down to the front door. My father was bundling my mother into a shawl, gingerly steering her out the door. She turned toward me, and I saw that her face was ashen and drawn. Her eyes were wide. There was no cheery wave, no, “Don’t worry, I’ll be back soon!” She didn’t say anything. The film froze, every detail crystal-clear: the dried eucalyptus on the nearby shelf in its earthenware jar, the wooden-framed mirror hanging on the wall.

Then my parents turned back to the door and the scene repeated, locked in an endless loop. Me, the door; the door, me. I recognized that this was the last time I’d ever seen my mother. No one knew it then, but a few weeks earlier she’d contracted encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain, during a family vacation to Sea Island, Georgia. My father took her to the hospital on a Friday; she died the following Tuesday.

Startled, I opened my eyes. Inside me, long-buried emotions dipped and swirled, a breeze stirring the air of some long-sealed tomb. I felt overcome by tenderness: for my doomed mother dying at the age of 37, for my terrified father left to raise my baby sister and me on his own. He’d suffered so much already — a Holocaust survivor, he’d watched his own world crumble beneath his feet as a boy. But I knew so little about any of that; he’d kept his own stories locked inside himself, always retreating when the line of questioning got too personal. This whole time I’d been reading his script about how men handle grief, never questioning why or who it was even serving.

With a near-physical jolt, I recognized that I was actually feeling this. For the first time in 40 years, I wasn’t pushing it away. I was feeling the deep sadness buried inside me. My whole life I’d told myself that it really wasn’t that big of a deal. But … what if it was? And what if I could handle it after all? It felt painless. Not numb — painless.

MDMA doesn’t really have a “peak” like LSD does. There’s not a rush of sensation and then suddenly you’re on the other side. But in the wake of what Julianna had said and the recovered memory that followed, something had broken open. I hadn’t researched the drug before our session, afraid of biasing my expectations or talking myself out of taking it. Later, I’d learn that therapists have been using MDMA in couples therapy for decades — and some studies suggest that it’s remarkably effective at helping to repair damaged relationships.

That’s not to say it’s entirely safe. MDMA is a “substituted amphetamine,” and at high doses it can cause dangerous fluctuations in temperature regulation, and long-term use can lead to severe health problems. In the moment, though, I felt no fear whatsoever. In fact, I couldn’t remember ever feeling so unguarded and yet safe.

Julianna and I faced each other then, blinking slowly in the candlelit glow. Renee smiled and handed me a new agey turmeric drink in a bottle. “I … I had this memory,” I began. “It’s been decades since I even thought of it.” I gave them the thumbnail sketch, struggling to express the sense of acceptance and relief washing through me. Renee nodded her head. “It’s called ‘fear memory extinction.’ You’re reintegrating a traumatizing experience. That’s one of the gifts of the medicine; it allows us to safely revisit those memories so that we can store them properly.”

Weeks before, during that awful fight, Julianna had told me that all she wanted was to be outside “the story” for a moment. Now we were. Everything we’d convinced ourselves of — that I was despondent and unreachable, that she was emotional and needy — it was all just the shorthand we’d created, the years of conflict standing in for honest communication. This moment of clear-eyed sight we’d been given was a wild and precious gift, and we’d be foolish not to at least try to work it out.

Maybe we were meant to split up; I really didn’t know. But if we were, it would have to be from within this place, the land beyond stories. I felt something dropping away then, withered leaves that had served their purpose, ready for mulching. I looked across the room at Julianna, and she glanced back at me, and without a word passing between us I knew she knew it too. Even today it’s this moment that stays with me: Julianna and I seeing each other as if for the first time.

Eventually, some unseen page turned and we all knew it was time for the night to end. Julianna and I hugged and thanked Renee effusively. Julianna handed her our payment for the experience, $550 in crisp new bills, and we walked back downstairs to the now-empty parking lot. The air felt cool and wet, delightful on my warm skin. We drove home through the darkness, undressed and clambered into bed. There was nothing to fix, nothing to do. Our daughter was with her grandmother, sound asleep and safe. Soon we were too.

Back when I was a teenager, the mornings after a trip would have an air of unreality about them. In daylight, I’d find it hard to square the waking world with what I’d experienced the night before. But now, as I blinked myself awake, I felt the inverse: I knew, without any shred of doubt, that what I’d felt the night before was real. Julianna sat up, eyes bleary. We looked at each other and then collapsed into giggles. “What … happened?” she asked. “Beats the hell out of me,” I said. “Let’s make some breakfast.”

Last night’s rain had blown over, and crisp spring sunlight flooded through the bare-branched trees outside. We didn’t talk much as we ate, but that was OK. Our bond felt like a near-physical web connecting us. The need to figure out exactly what we were doing with our marriage was a faint rumble in the distance.

Julianna brewed a pot of tea. I felt the potential of this moment, like the board had been wiped clean. It’d been a long, long time since I’d felt this way. I didn’t know it then, but we were inside what’s called a “critical window,” a period following an MDMA experience in which the brain has the potential for a profound reset. As rodent-model experiments suggest, we actually return to childhood behaviors, becoming more social and open to bonding. It’s not a guarantee — and it requires a stable and supportive environment — but the effect can be truly revelatory. As Julianna and I hung there in that window on that gauzy morning after, we experienced it firsthand.

“You know, when we first got together, we were babies,” Julianna said, pouring me a steaming cup of oolong tea. “We were half-formed. My mom had left my dad just a few years before, and it felt like everything I’d grown up with had just been ripped up and thrown away. And I know your childhood was hardly easy.”

“After my mom died, my father kind of just … disappeared. Like his emotions went offline,” I said. “It seems so obvious, but now I see all the ways I was just reciting his lines.”

We sat in silence, each of us lost in our feelings. Something had shifted overnight. For so long, I’d worked so hard not to feel; now a faint wave of grief washed through me, gratitude intermingling with awe. I felt the thrill of discovery, like I’d stumbled upon a whole new continent inside myself. There was more to know. And suddenly, a way forward with Julianna.

“It’s funny,” I said. “It wasn’t like I didn’t know my mom’s death was awful. But I’ve lived my whole life feeling like I had to say it was no big deal, to just get over it.”

“Like your father did?”

I nodded. “Like my father did. Maybe it’s time to face the fact that I’m hurt too.”

Now I turned to her, studying her face. It was the same one I’d woken up next to all these years, and yet somehow different, the planes of her cheeks and jaw made new and unfamiliar.

“I felt something really big last night,” I said. “I felt our contract. Like, our souls have business with each other. I never wanted to break up with you, but I didn’t know what else to do. Feeling alone is the story of my life.”

“Baby,” said Julianna. “I know. It’s time to do something different.”

In the coming months, I felt my life changing in ways I’d never believed possible. Maybe it’s a trope to say that I took drugs and my wife looked beautiful and I realized what I was about to give up, but what I was shown that night on MDMA was so much more. Even today (and it’s been eight years) the sense of truthfulness persists. What we’d seen and felt in the medicine wasn’t some drug-induced fantasy. Despite everything I’d feared as I held that little capsule in my hand, what I’d been shown was trustworthy and true. I’d been hurt in early childhood — badly. Ever since, I’d stuffed my emotions down, determined to protect myself from ever feeling that kind of pain again. But that night in Renee’s office I’d gone deep into grief, and I’d survived. Maybe it was time to begin taking off my armor.

It’s not like everything that came after was perfect, there were still moments when I thought we might not make it after all. But things were shifting. One day, with no drama whatsoever, I realized Julianna was right: It was time to leave our house. It was too big and expensive and somehow never really felt quite right. My identity as a recording engineer was a story, just like all the others, and not a particularly believable one. And so I started tearing it down: figuratively and literally. I took apart my beautiful studio and sold every last piece of it.

A few mornings later, I looked around in vain for my socket wrenches. “Hey, where’s the tools that were at the top of the stairs?” I called up to the kitchen. Half hearing Julianna’s muffled reply, I cursed quietly and stomped upstairs. She was in the kitchen, wrapping dishes in newspaper.

“Hey, my socket wrenches were out here. Where’d they go?”

“Yeah, they’ve been sitting there for a week. I nearly tripped on them, so I put them away.”

“Well, I was using them,” I said, a harsh edge creeping into my voice. “I wish you wouldn’t do stuff like that.”

Julianna rolled her eyes, and I felt my body tense for the familiar face-off: First she’d complain that I left my things all over the house, then I’d angrily explain why having her derail my projects was so irritating. We’d squabble for a few minutes before breaking to our corners of the house for hours.

But here’s where it got weird. I felt like we were passing through some sort of membrane, out of our normal roles and into something more expansive. We’d had this same stupid argument hundreds of times. What if we chose a different way? I relaxed my face and dropped my shoulders.

“This is … trippy,” I said. “Do you feel it? We were just about to have this fight all over again, and … who even cares? I’m sorry I left my tools out.”

“And I’m sorry I put them back without asking you.” Julianna’s face looked calm and serene.

“This is the medicine, isn’t it?” I said.

“No. This is us,” Julianna replied with a smile.

A few weeks later, the moving truck arrived. We left our beautiful Craftsman home for the last time and soon pulled up in front of a fixer-upper a few miles away. Over the next couple of months, the three of us — Julianna, myself and our now 11-year-old daughter — worked hard, ripping up carpeting and reshaping our new house. As we did, we bonded in common purpose. We didn’t always nail it, but more and more, our inevitable disagreements became invitations to draw closer. And in these moments, I felt like the luckiest man alive.

There was one other thing Renee told us, and it hasn’t left me since: Some people call MDMA “heart medicine.” I hadn’t known how badly I needed it.

This piece is the second in our series, Heart of the Matter, a special collaboration from Narratively and Creative Nonfiction that explores love and matters of the heart. You can learn more about this special series and check out the rest of the stories as we publish them here over the next few months.

Seth Lorinczi is a Portland-based writer and journalist. His first book — Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir — was published in May 2024. An exploration of the use of psychedelic therapy to address ancestral trauma, the book leapfrogs from Portland’s ayahuasca basements to the darkest days of World War II.

Jesse Sposato is Narratively’s executive editor. She also writes about social issues, feminism, health, friendship and culture for a variety of outlets. She is currently working on a collection of essays about coming of age in the suburbs.

Jane Demarest is an illustrator, based in Philadelphia. Some of Jane’s clients include McSweeney’s, Courtney Barnett, Field Meridians, Off Assignment, Phish and Wilco. Their work has been recognized by the American Illustration Awards.

What a talented writer! This was written so perfectly, each moment and character deftly described. The most interesting thing is how keen and ego-less the self-exposure is. Really beautiful work.

In the early 80s when MDMA was legal and called Ecstasy (this was before designer drugs) and readily available my ex-girlfriend and I tried it. We couldn’t be together and we couldn’t stay apart. It was endlessly agonizing. I got a couple doses, we went to the shore and took it. We were still a couple of years away from really dating again but in one session, we let go of so much and were able to be together in a whole new way and communicate on a level that had been just too fearful. At any rate we’ve been married for 35 years and we both credit Ecstasy with the breakthrough we needed.