What Is a Hermit Crab Essay, Anyway?

In this craft piece, journalist Suzanne Cope explains this writing technique, and breaks down three essays in which writers employ it, each with nature at the center in some way.

This piece is part of a series called Creative Nonfiction Craft Classics, a special collaboration from Narratively and our partners at Creative Nonfiction in which we’re republishing classic pieces on the craft of writing from the Creative Nonfiction archive. This story was originally published as “The Essay as Bouquet” in CNF’s 61st issue.

Ambrose Bierce, the American editorialist and journalist, wrote in his 1909 craft book, Write It Right, that “good writing” is “clear thinking made visible,” an idea that has been repeated and adapted by countless writers over the past century. My own addition would be to add that the act of lyric essay writing not only makes thoughts visible but also institutes order and layers meaning when it is not always immediately apparent. And although ideas may begin free-form or as stream of consciousness, on the page or screen, we make the jump from internal to external. We craft them into a form, whether chronological or otherwise.

One such approach to form is the “hermit crab” essay, so named by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola in their craft book Tell It Slant. Miller later defined it in an article for Brevity as “adopt[ing] already existing forms as the container for the writing at hand, such as the essay in the form of a ‘to-do’ list, or a field guide, or a recipe.” This approach creates meaning by juxtaposing the personal story with its imposed “container,” allowing the more traditional narrative to be in conversation with our personal, cultural, and/or scientific assumptions and understandings of the chosen form.

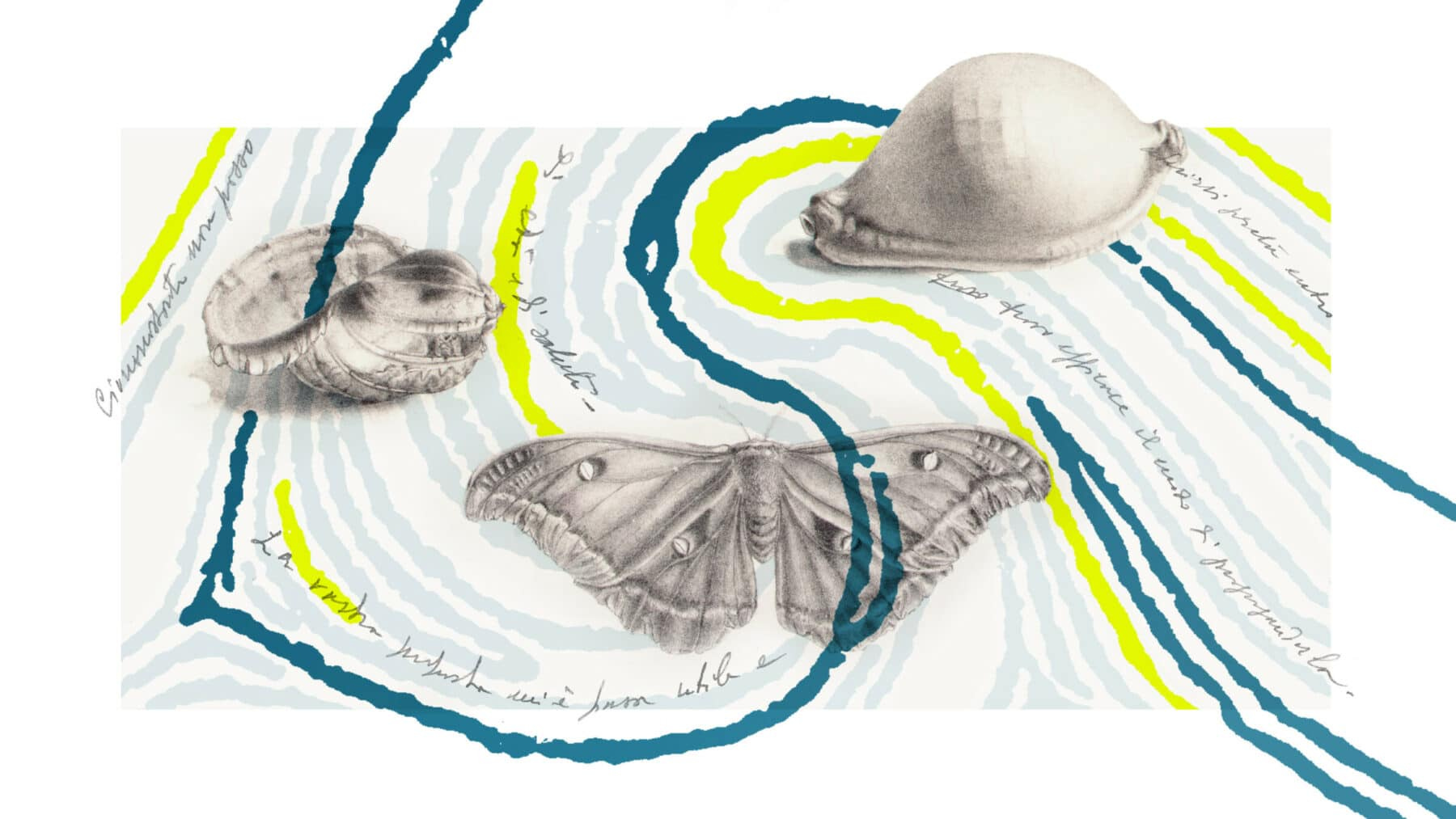

“Hermit crabs,” Miller explains, “are creatures born without their own shells to protect them; they need to find empty shells to inhabit (or sometimes not so empty; in the years since I’ve begun using the hermit crab as my metaphor, I’ve learned they can be quite vicious, evicting the shell’s rightful inhabitant by force).” Ironically, however, most containers that writers find are of the nonorganic variety: a shopping list, a course syllabus—not unlike the hermit crab who makes its home inside a bottle cap. Here, we will look at a few examples that do employ natural forms as a container, encouraging a conversation between the human-made and the natural world.