Penny for Her Thoughts

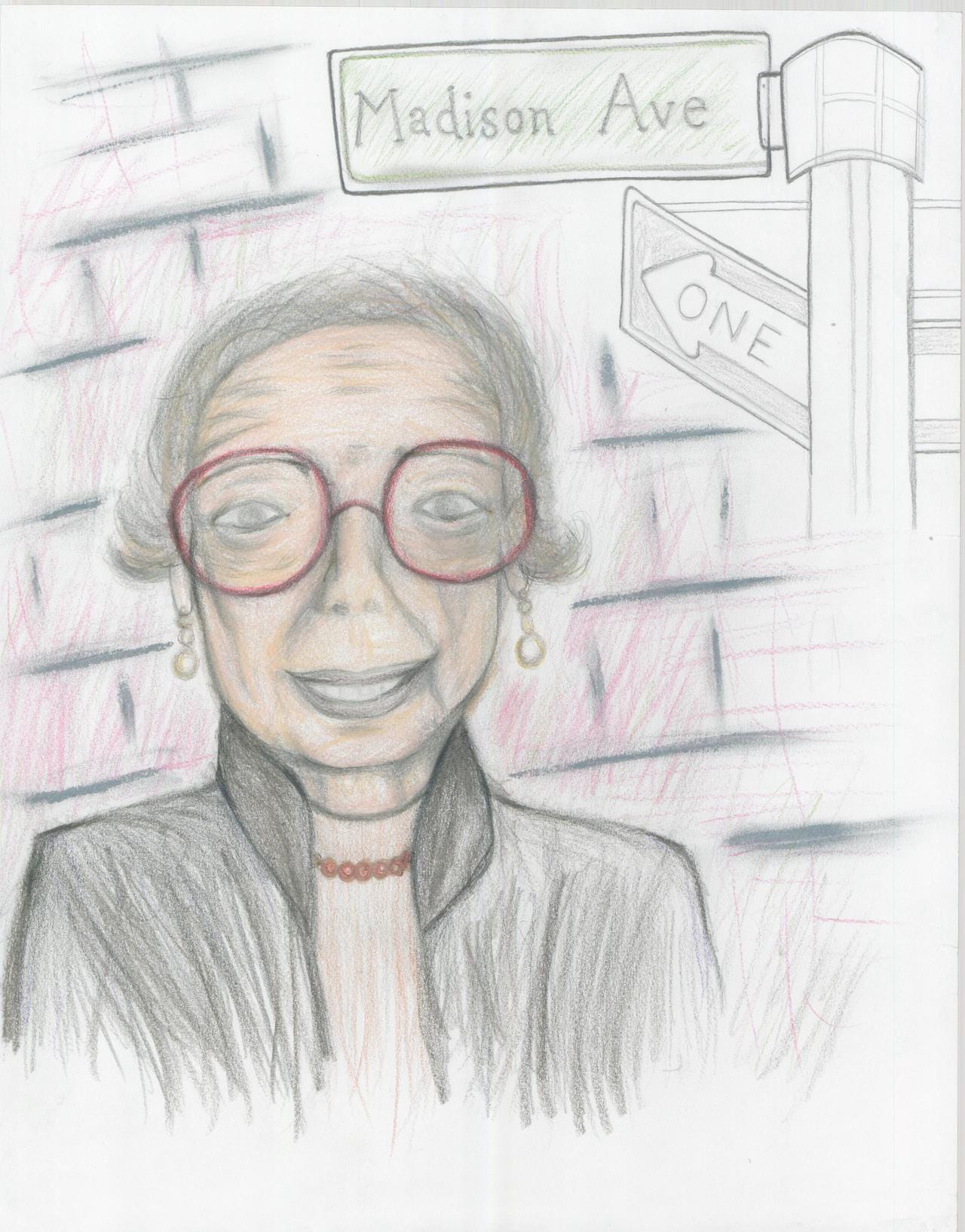

This whiskey-swilling, punctuation-loving, Mad Men-era advertising veteran has tried to retire—really, she has—but ninety-three-year-old Penny Speckter just keeps on chugging.

It’s two days before The General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen’s annual awards ceremony and Penny Speckter, ninety-three, is drafting a script for the evening’s events. No one’s asked her to—she didn’t need to be asked.

November wind is rolling off the East River as the sun sets, but it’s warm in Peter Cooper Village, the red-bricked Manhattan apartment community on the East Side where Speckter lives. She’s had the same address since January of 1949, when she and her husband moved to New York, the city where they launched their own Mad Men-era ad firm. It’s also where she enrolled in college at age fifty-six, boarded her first plane overseas at sixty-eight, and camped out in her apartment, eating canned food and drinking whiskey sodas, during the blackout that followed Hurricane Sandy.

When we meet at her apartment, Speckter, rosy-haired and smartly dressed with giant red-framed glasses, opens the door and greets me with: “Oh good, you wear a …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.