Secrets and Nightmares of the Teenage Circumcision Circuit

In South Africa thousands of boys are initiated into manhood each year, but all too often they lose far more than they gain.

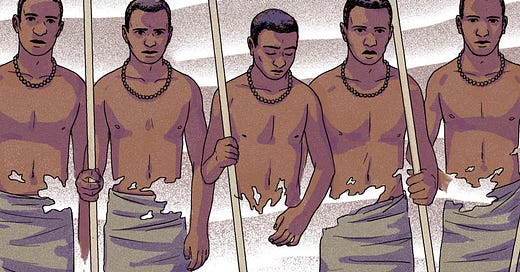

Illustrations by Hertz Alegrio

The sun is drooping in the December sky as cicadas weave ominous melodies into the summer air. Their shrill vibrato is the soundtrack to Azola Nkqinqa’s last day as a boy. It’s the time of year when Nkqinqa, 18, and about 50,000 other South African boys, come to one of the many remote initiation schools in order to learn how to be a man. This school is located in the Eastern Cape province — the country’s poorest. In the Xhosa culture, the transition into manhood is marked by a month of instruction from elders, who teach the teens how to be a father, a husband. The Xhosa boys are also circumcised during this time, and most years these schools make headlines because dozens of the boys die during the process.

Nkqinqa is feeling particularly insecure. It is customary for the patriarch in a family to send a boy off, but Nkqinqa’s father has not been a part of his life for several years, and three of his uncles are dead. So a neighbor named Patrick Dakwa has a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.