Single Woman Seeks Responsible, Caring, Tough…Uncle

In Pakistan when a child has no father, his uncles step in. As a single mother in America, this was far from my reality, but my teenager needed a surrogate dad.

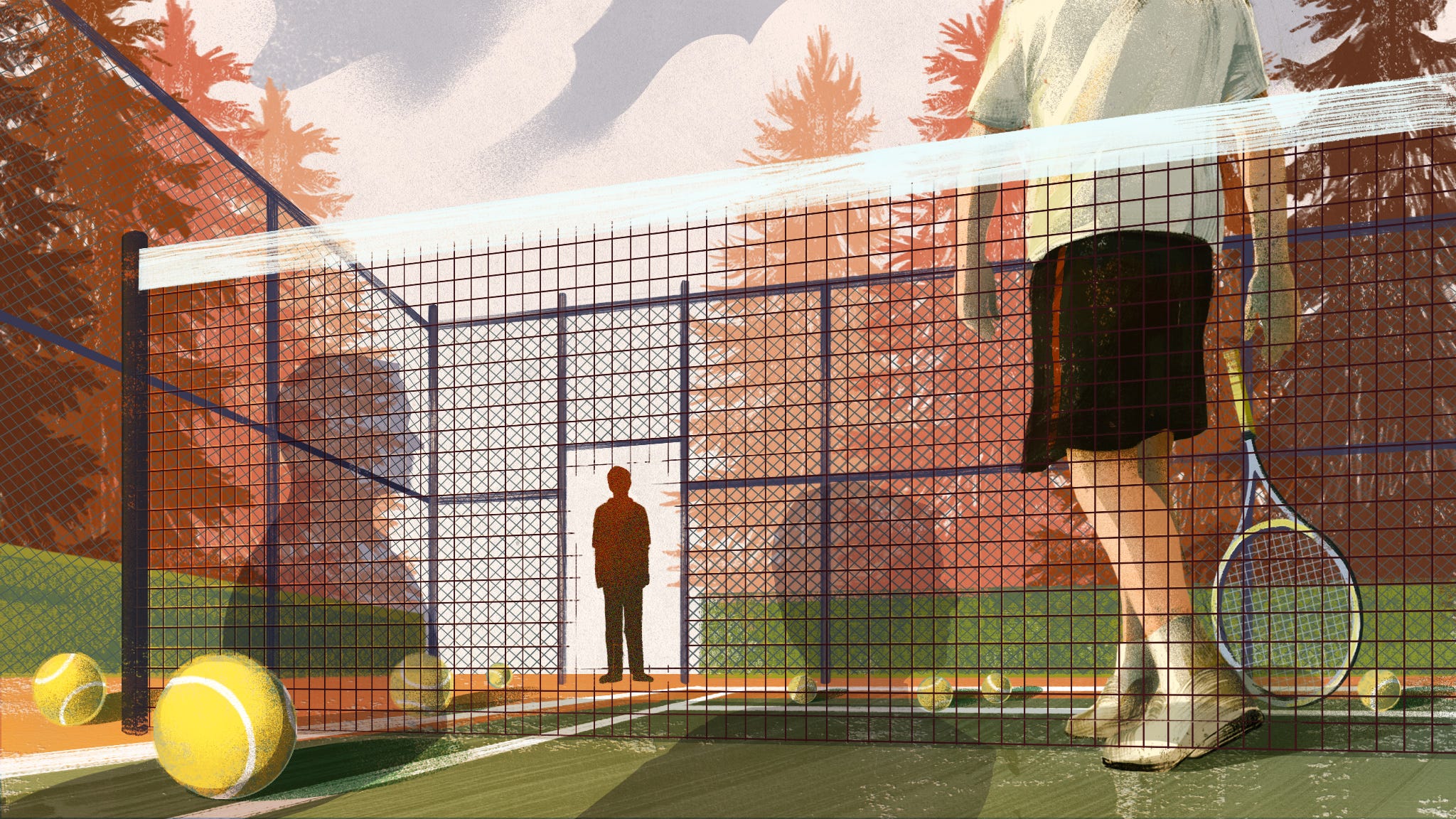

Illustrations by Cornelia Li

Four years ago, I spent a month in northern Pakistan, researching Pashtun culture for my latest novel. My story centered on a pair of Pashtun siblings who migrate to the U.S. when the brother is recruited to play squash – the Pashtuns are among the best in the world at the game. Later, the sister character makes the mistake of falling in love with a Jew. So in my travels I wished to learn the Pashtun code of honor and their attitudes toward romantic love.

I stayed with a host family who took me around to various villages. Everywhere we went I was asked about my family. I had two grown sons, I explained to them, whom I’d brought up mostly as a single mother. They were aghast.

“Where were the uncles?” they asked.

Damn, I thought. Where were the uncles? Plenty of them existed – my brother and my ex-husband’s five brothers. But none of them had acted in accordance with Pashtun tribal norms.

When a father dies there, the uncles step in. They don’t take the place of …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.