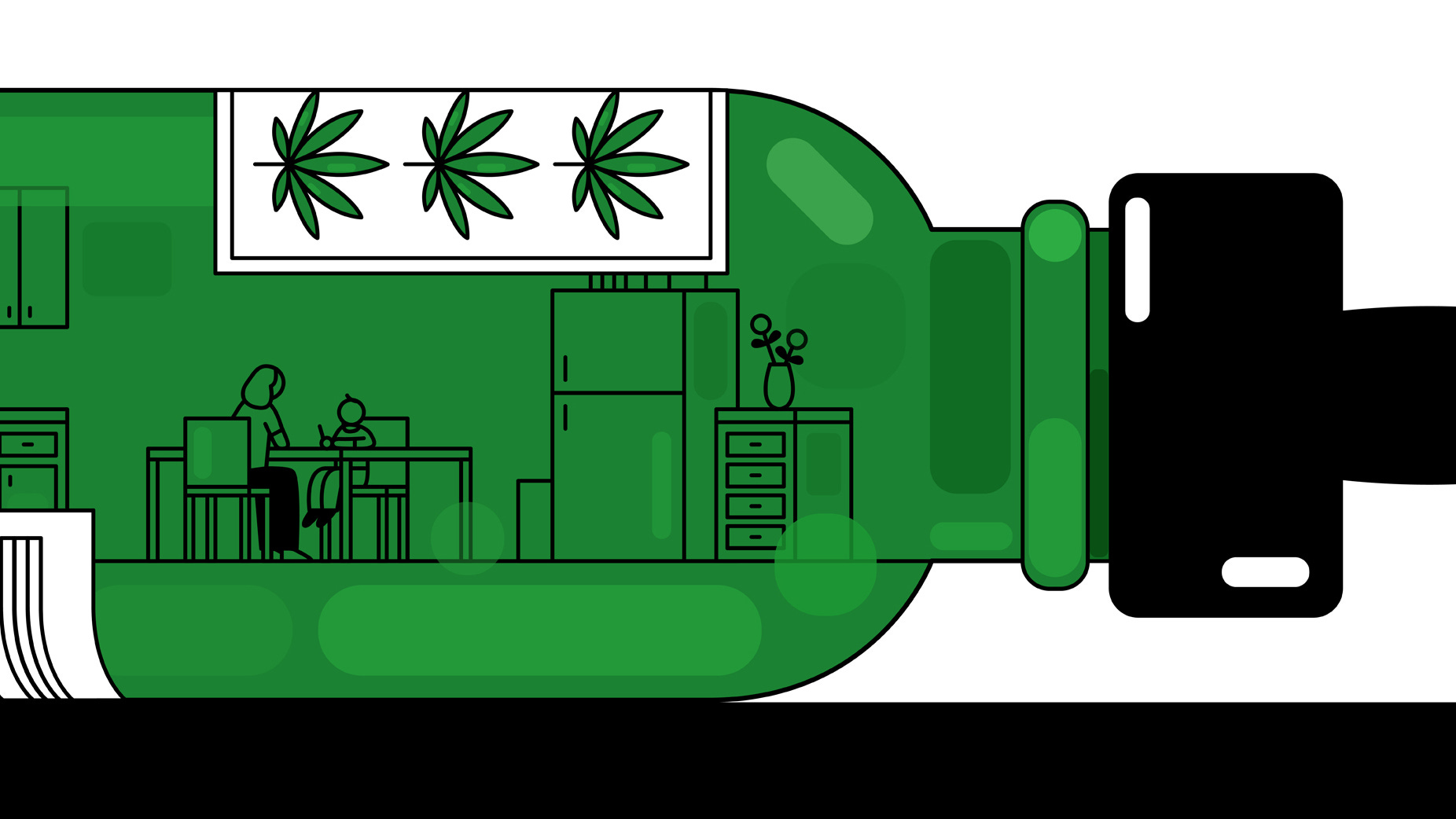

The Autism Moms’ Cross-Country Drug Ring

How these minivan-driving mothers built an illegal network to provide medical marijuana for their autistic kids.

When Sarah’s child was diagnosed with autism, Sarah snapped into action. “We spent hours and thousands of dollars on different therapies,” she says. “Occupational therapy, speech therapy, play therapy, ABA [applied behavioral analysis] therapy. We did 26 months of elimination diets for a number of reasons, to identify triggers, allergies, sensitivities.” Nothing worked, so she looked for new options.

“Right off the bat, I asked what was at the forefront of autism treatment? What was at the cutting edge — that is not bleach, shots of gold, or hyperbaric treatments that we couldn’t afford?”

She kept finding the same answer: medical marijuana. She was curious, but not ready, even as her child became more and more difficult to handle. She remembers him flinging himself off the second floor of the house, eating things that weren’t food, and smashing lightbulbs. A child that had been easy and mellow as a baby and toddler, who had been able to say “uh-oh” after fallin…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.