The Bittersweet Bonds of a Post-Prison Family

At an innovative treatment program in L.A., violent offenders and other paroled ex-cons take baby steps back to society—and test-run the delicate mission of reuniting with those they had left behind.

Interview by Daniel Cassady

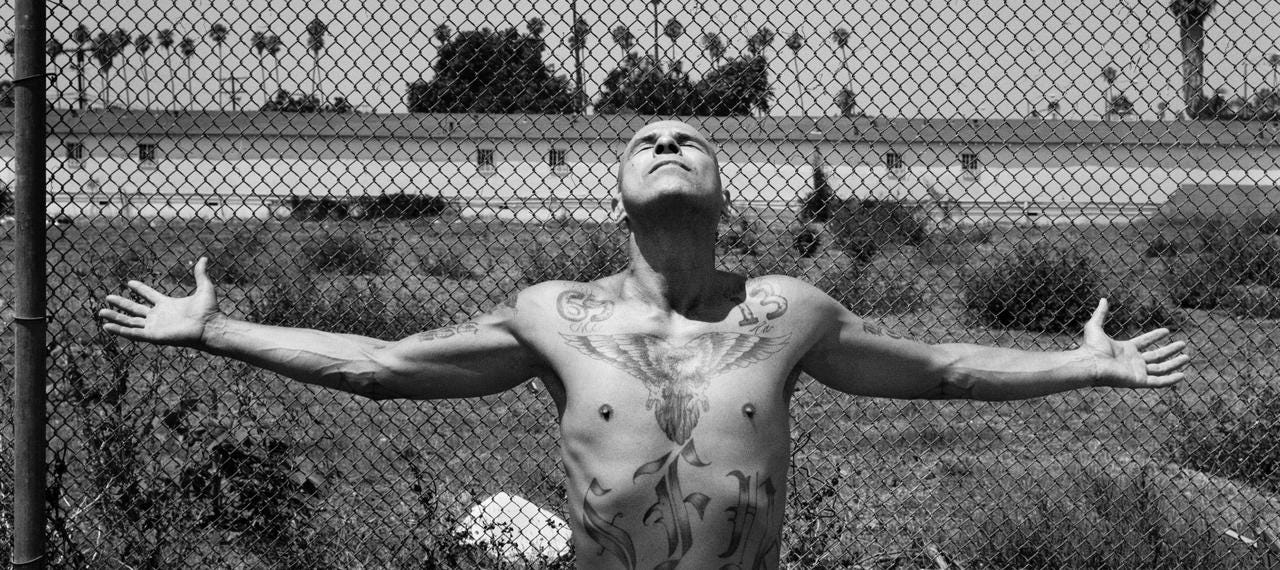

“I did time for eight parole violations,” said David Lee, 40, from San Fernando Valley (pictured above). Lee’s life is shaped in part by California’s “Three Strikes” law, enacted in 1994, which imposes a life sentence for a wide range of crimes upon people who have two prior convictions considered “serious” by the state. Lee is one of those people. “I have two strikes so I realized that I have this last chance before I wind up with a third strike and go away for life. That is why I came to the Walden House. This is it for me! I am still here.”

Photographer Joseph Rodriguez never strayed far from home, even as he traveled the globe. His career as a documentary photographer has stretched from 117th Street in New York’s Spanish Harlem to the barrios of Los Angeles, and taken him to Mexico, Romania and Kurdistan. But the drive that compels him to make photographs hasn’t changed since he first loaded a roll of Tri-X into a camera. Rodriguez takes photographs to op…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.