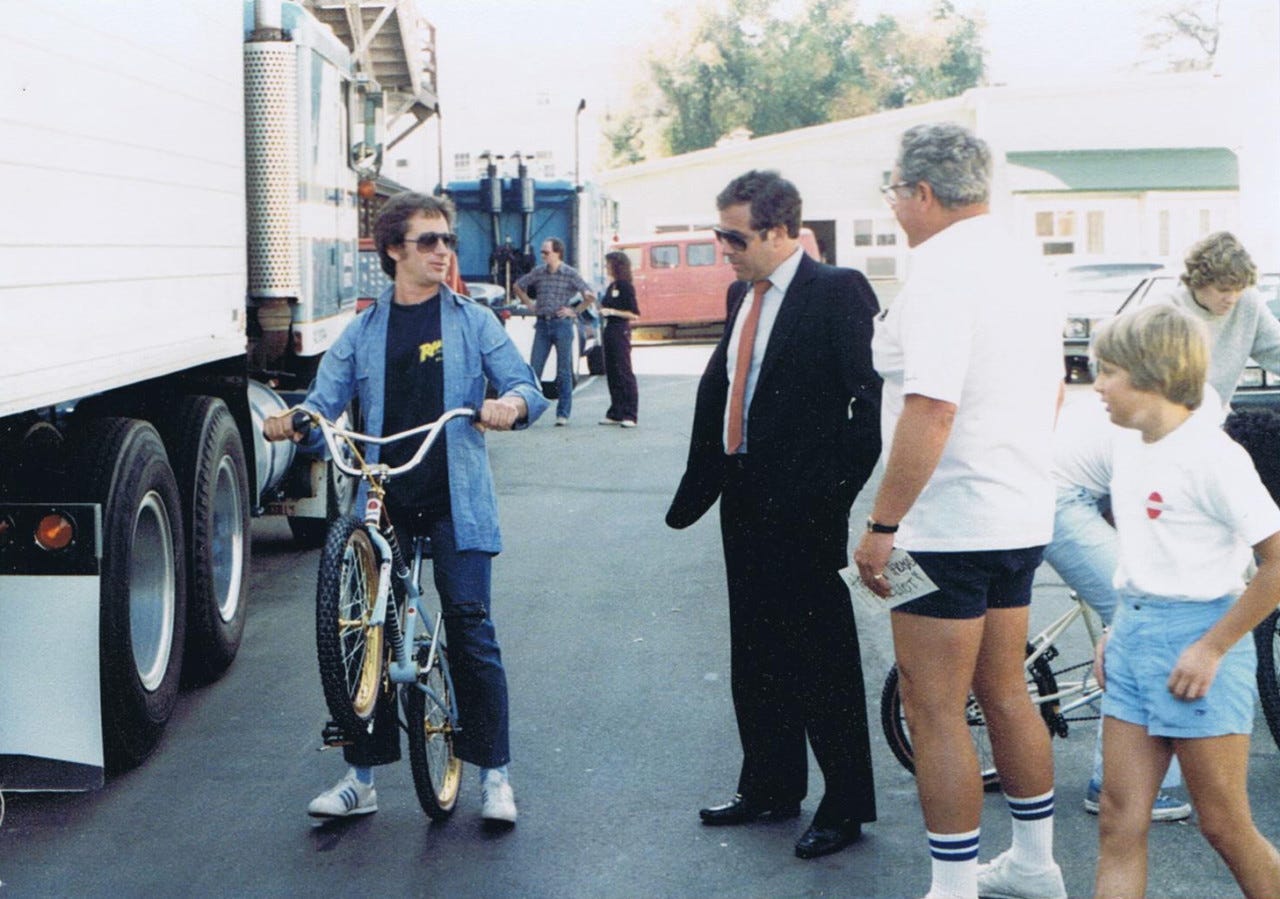

The BMX Boys of E.T.

The untold story of the bike broker and the fearless riders behind the Spielberg blockbuster and its legendary chase scene.

Robert Cardoza, Greg “Ceppie” Maes and David Lee were five minutes late to a private screening of Steven Spielberg’s "E.T." at Culver Studios in California in 1982, months before the film would open to the public. It was the first time the three boys, hired as BMX stunt doubles for the movie, would get to see their work on a big screen. As they rushed up to the studio entrance, they came upon a locked gate and a woman holding a little girl’s hands. The woman was kicking the gates with her heels and screaming, “Let us in, my daughter’s in this movie!” The boys were convinced they had blown their chance to get in. It turned out to be Drew Barrymore’s mom having a tantrum. Her outrage and insistent pleas eventually got them all in to the screening.

As the boys quickly settled into their seats, they eagerly anticipated the bicycle scenes. None of them had any idea what role their work would play in the overall movie.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.