The Brave and Tragic Trail of Reverend Turner

As the crucible of desegregation enveloped town, a white minister implored his congregation to do the right thing. The violence that followed haunted him until his dying days.

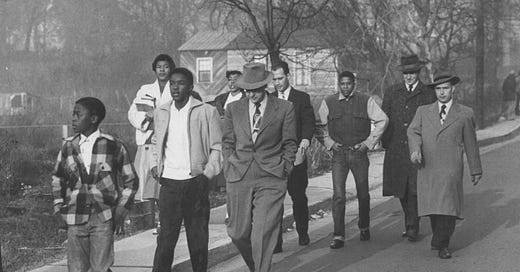

Photo by Don Cravens/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

The Reverend Paul Turner trudged up Broad Street. He shoved his ungloved hands in his overcoat pockets and pulled his dark fedora low against the misty mountain morning. Leo Burnett, a supervisor at the local hosiery mill, walked beside him. An African-American woman passed them on her way to work. A photographer for Life followed. The two white men were heading into the black neighborhood of Clinton, Tennessee, to meet white attorney Sidney Davis and a handful of black teenagers. Trailing them were two members of the White Citizens’ Council.

“Preacher,” yelled one, “what business have you got up here?”

“If a lot of these ‘Negro lovers’ would keep their noses out of it,” said the other, “things would be all right.”

(When Turner retold the story for a federal court the following July, he clarified that their real words were “commingled with profanity as well as vulgarity.”)

It was Tuesday December 4, 1956. Desegregation had come t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.