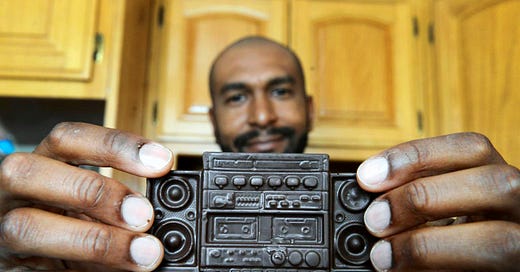

The Chocolatier for the Hip-Hop Ear

A soul-searching Los Angeleno finds religion in the rhythm of hip-hop and seeks to spread the faith, one sweet boom-box-shaped bite at a time.

Listening to Public Enemy’s “By the Time I Get to Arizona,” Marcus Gray unloads hardened chunks of semi-sweet Belgian dark chocolates into a three-gallon double boiler pot, mixing carefully until they dissolve. After twenty minutes at 300 degrees, the chocolate melts into a silky brown liquid. Still mixing, Gray adds almonds, sea salts, and bits of ginger or turmeric.

Then the magic happens.

He pours the velvety concoction into plastic BPA-free molds that he made himself, and lets each creation cool. By now he’s listening to the lectures of the Eastern philosopher Alan Watts. Fifteen minutes later, and bam: His kitchen in Mount Washington, a quiet neighborhood in the hills of northeast Los Angeles, is transformed into a virtual candy store of chocolate ghetto blasters, microphones, hard-shelled sneakers, DJ mixing boards and cassettes. He makes hip-hop morsels in raw cane sugar lollipops too, with flavors like apple, orange and fruit punch.

Five years ago, Gray sta…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.