The Detective Writer Who Hates Murder

Former Narratively senior editor and contributing writer W.M. Akers on the third book in his acclaimed trilogy, his writing advice and staying away from fictional murder as much as possible.

W.M. Akers isn’t a fan of real-life murder, but he thinks a lot about how much people love fictional murder. “I think it's very interesting how people tend to walk around agreeing that murder is a bad thing, but as soon as they sit down for fiction, they tend to become a lot more ambiguous about that,” Akers says.

Westside Lights, the third book in Akers’ Westside trilogy about Gilda Carr, a badass detective who investigates “tiny mysteries,” does have murder in it. But Gilda’s tiny mysteries are beyond that — they’re the type of puzzles that have us questioning our relationships, day-to-day actions, and choices late at night — because Gilda understands that murder is dangerous and best to stay away from when she can.

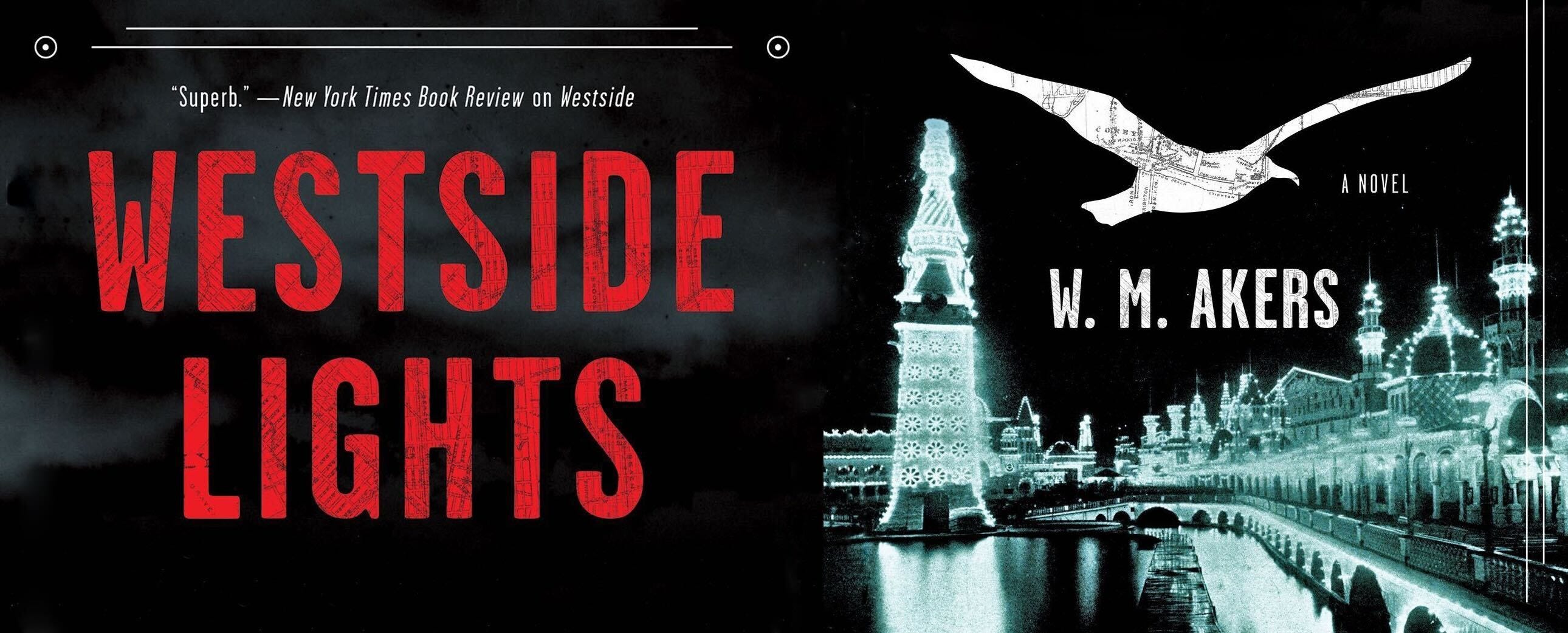

Since the release of Westside, the first book in the trilogy, the books have received rave reviews. Kirkus Reviews called Westside “addictively readable” and The New York Times said it was “superb,” later naming it a notable book of the year.

As Narratively’s former senior editor and longtime contributing writer, Akers has written pieces covering baseball player Tom "Shotgun" Rogers and one of the greatest trumpeters of all time, plus edited stories on topics ranging from real-life mermaids to ridiculous food fads.

In addition to his acclaimed novel series, Akers spends his days writing Strange Times, his newsletter that examines the wackiest stories from the 1921 New York Times, working as a writing coach, and creating Deadball —a tabletop baseball simulator.

Narratively sat down with Akers to talk about his trilogy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.