The (Literally) Unbelievable Story of the Original Fake News Network

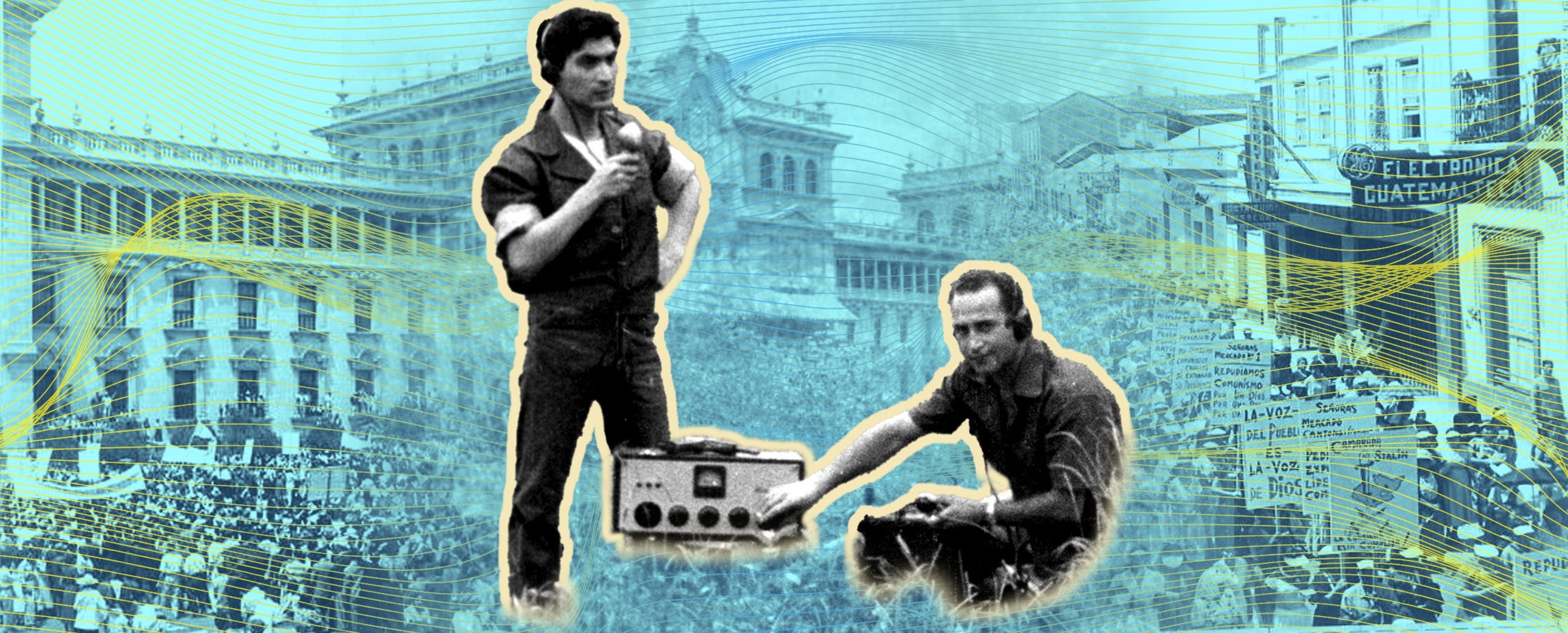

Once upon a time in Guatemala, the CIA hired a cocky American actor and two radio DJs to launch a revolution and oust a president. Their playbook is being used against the U.S. right now.

Guatemala City looked like a ghost town.

The capital’s 450,000 residents hid in panicked self-quarantine, waiting for the first wave to arrive. World War I–style military planes periodically flew overhead, firing warning shots and dropping leaflets telling people to either flee or stay indoors.

A civil war was moving toward them.

All week, Guatemalan radio had been blasting the news of gruesome battles around the country. The newspapers were going crazy. Two Americans in a tourist plane had been shot down by Guatemala’s Communist army. Refugees were fleeing to Mexico while 400 injured Communist troops were retreating to the capital for medical treatment.

Now, on Saturday morning — June 26, 1954 — radio news broadcasts reported that two columns of anti-Communist patriots calling themselves the “Liberation Army” were 60 kilometers from the capital. And marching fast.

All vehicles were now military targets, the radio warned, so citizens should stay out of their cars. …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.