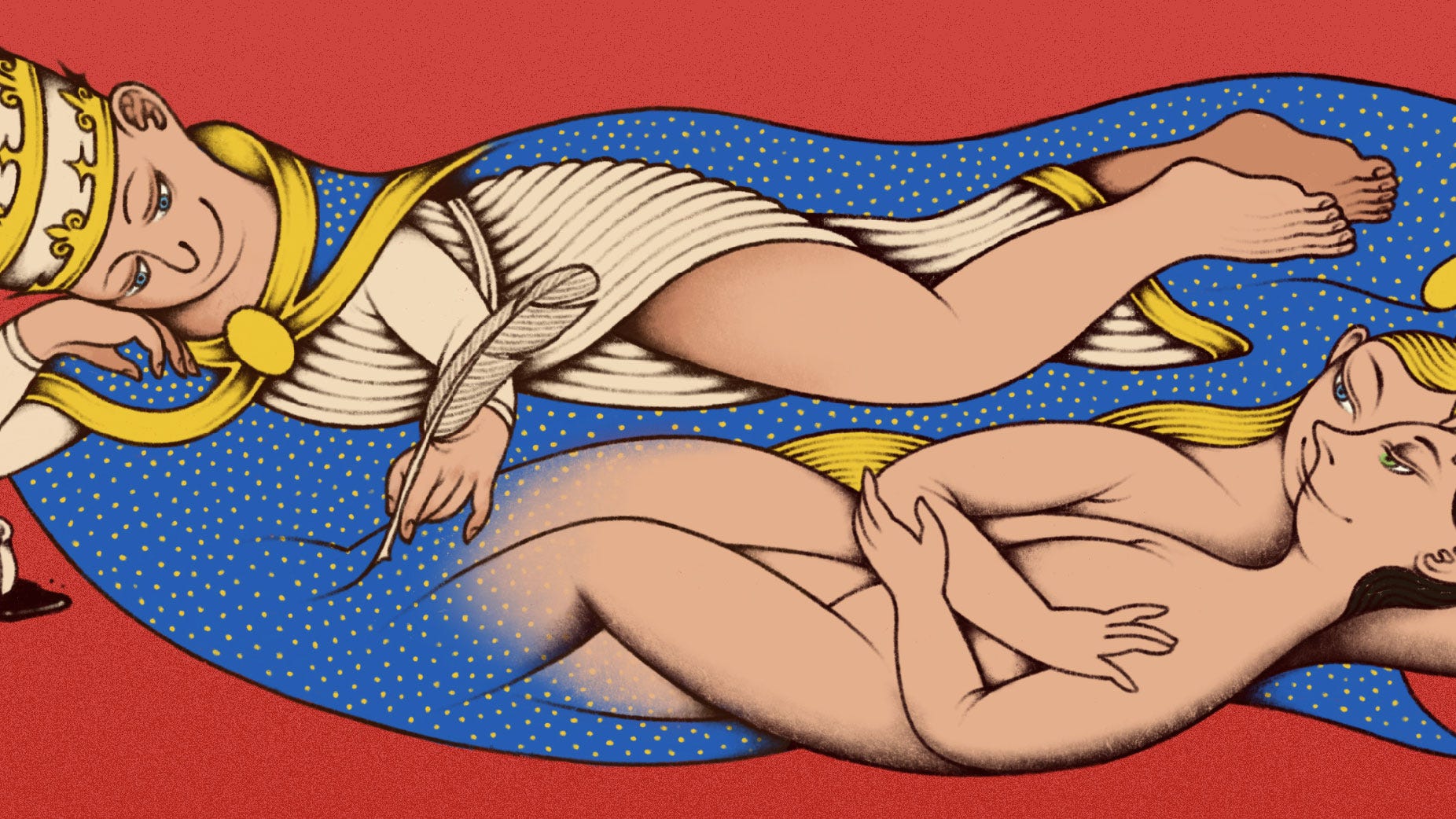

The Pope Who Wrote an Erotic Novel

Before his rapid rise to the top of the Catholic Church, Pius II had a secret passion for scandalous stories. And they may have been inspired by his own life.

Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus caught the attention of King Frederick III of Germany, the future Holy Roman Emperor, with his talent for words. King Frederick named Bartholomeus poet laureate in 1442 and commissioned him to write his own royal biography. The king may not have known that Bartholomeus had a far less regal side interest. According to Absolute Monarchs, by historian John Julius Norwich, over the next three years, while working in the royal chancery in Vienna, Bartholomeus wrote a large amount of “mildly pornographic poetry.” And then there was his magnum opus: The Tale of Two Lovers, or Historia de duobus amantibus, an erotic novel that he penned in 1444. This dalliance with erotic literature is even more surprising given that Bartholomeus later took on a much more high-profile position: In 1458, he become Pope Pius II.

The Tale of Two Lovers is set in Bartholomeus’s hometown of Siena, Italy, and it details a passionate affair between Lucretia, a married woman, and Euryalus, a man-in-waiting to the Duke of Austria. In the book’s preface, Bartholomeus admits that his novel may be “offensive and disgusting” to some readers, but he argues that people should read it because love “is a subject which delights young minds.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.