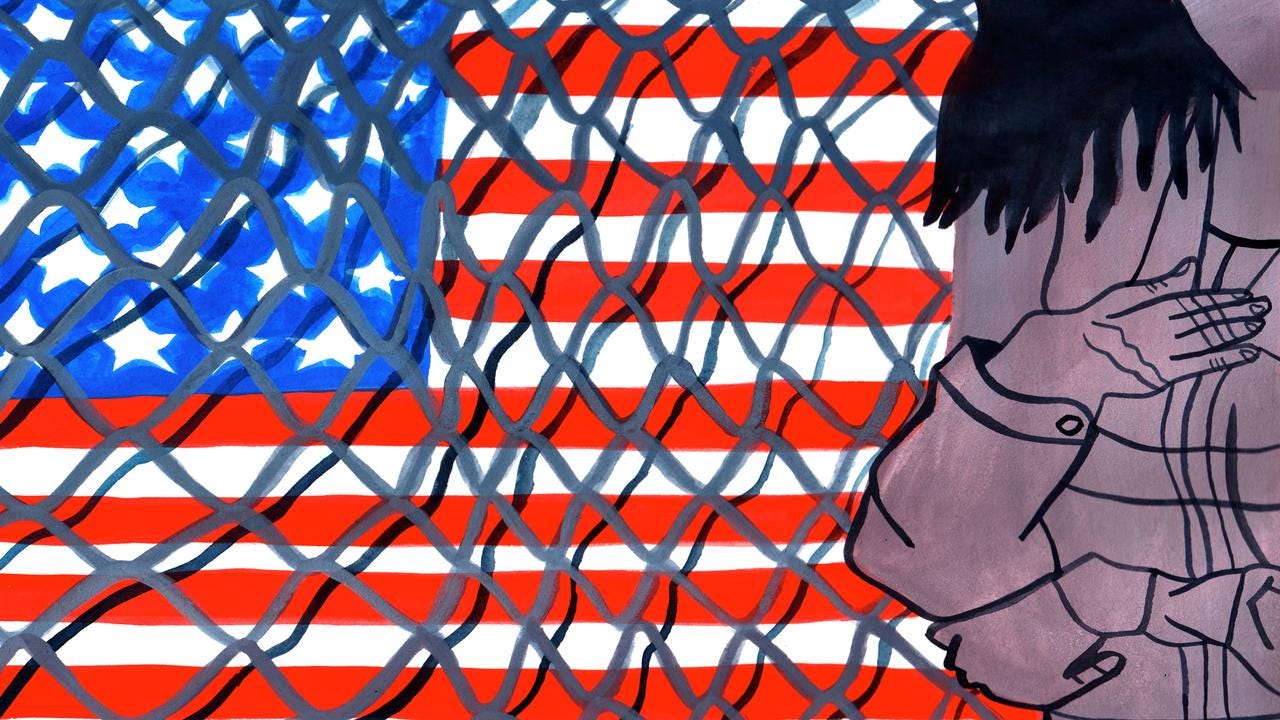

The Secret Life and Terrifying Journey of a White-Collar Undocumented Immigrant

With my perfect English, stable finances and penchant for Prada, I never saw myself as anything but American—until U.S. Immigration decided to throw me out.

Illustrations by Danielle Chenette

I had known Oscar for a year and a half when he asked me to marry him. We were on a bench in Battery Park and he was feeding the squirrels. I was shocked.

“Marry...oh my God...Oscar, I’m flattered. But I don’t think I’m ready.”

I was holding his hand. He looked so sad. At 32, I was still recovering from the breakup of a lifetime with a man I’d once considered to be my soul mate, a childhood friend of my late brother’s — both of us born in the former Yugoslavia. Brandon, the ex, was now a U.S. citizen and I was in limbo, with no green card, hiding in plain sight.

I was essentially starting from scratch, an illegal immigrant who had all but grown up in the U.S. My father served as a Yugoslavian diplomat in Chicago, hobnobbing with Mayor Daley and the police commissioner. His first term in the U.S. began when I was four. That’s when I got my very own Social Security card, courtesy of my father’s diplomatic status. I also learned to read and write in English…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.