To Be Read in the Event of My Death

A writer embedded in Afghanistan takes an intimate look at one of war’s most private and painful traditions.

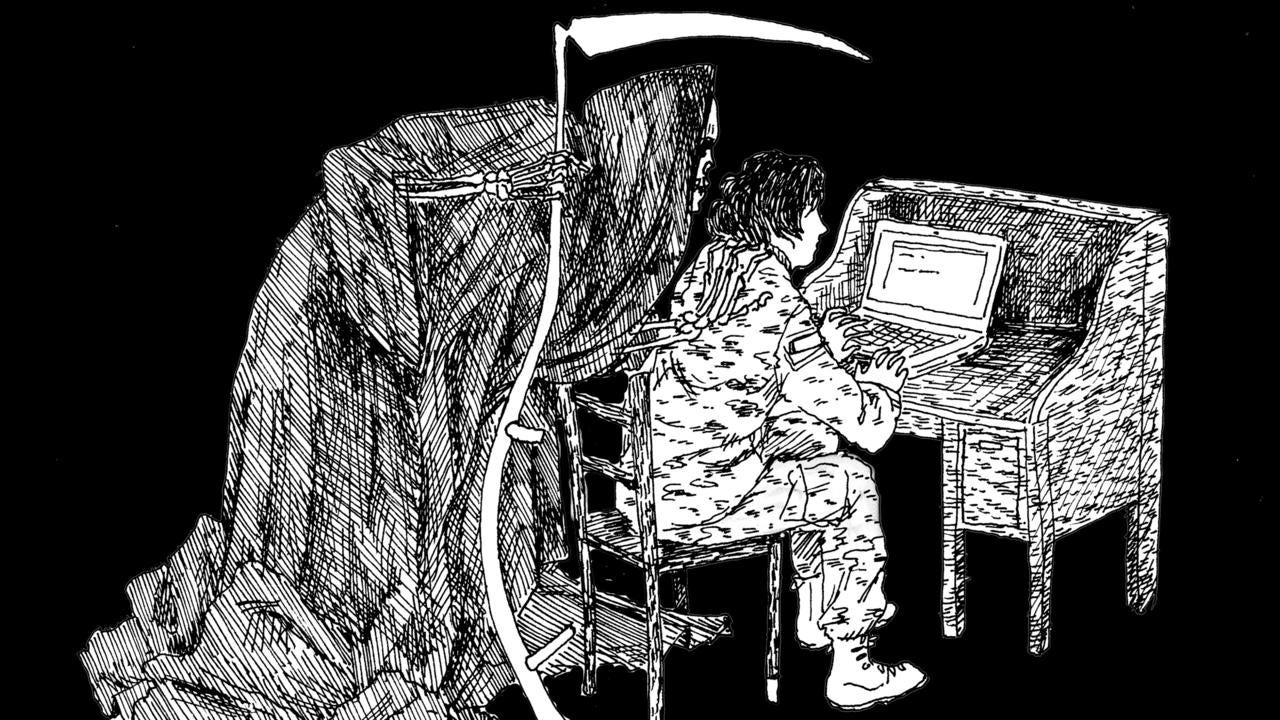

Illustrations by Julia Gfrörer

For two months before heading off to Afghanistan in 2010, where I served as a cultural advisor to two brigade commanders, I experienced recurring nightmares that always ended in death — my death.

In some dreams, I was taken out by a sniper perched atop a nearby building. As if cross-cut for a movie, this dream offered dual perspectives. I could both watch myself from the sniper’s point of view and feel the force of his precision shot.

As a cultural advisor, I knew that I would be regularly heading “outside the wire” to interview Afghans in small villages in an effort to document the availability of education, the need for medical care, tribal conflicts both new and long-standing, local attitudes towards the Afghan National Police and the Afghan National Army, and the threats that locals felt from insurgents.

I was no stranger to war. In December 2008 and January 2009, I traveled to Iraq as a journalist. While there, I quickly became accustomed to the evening…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.