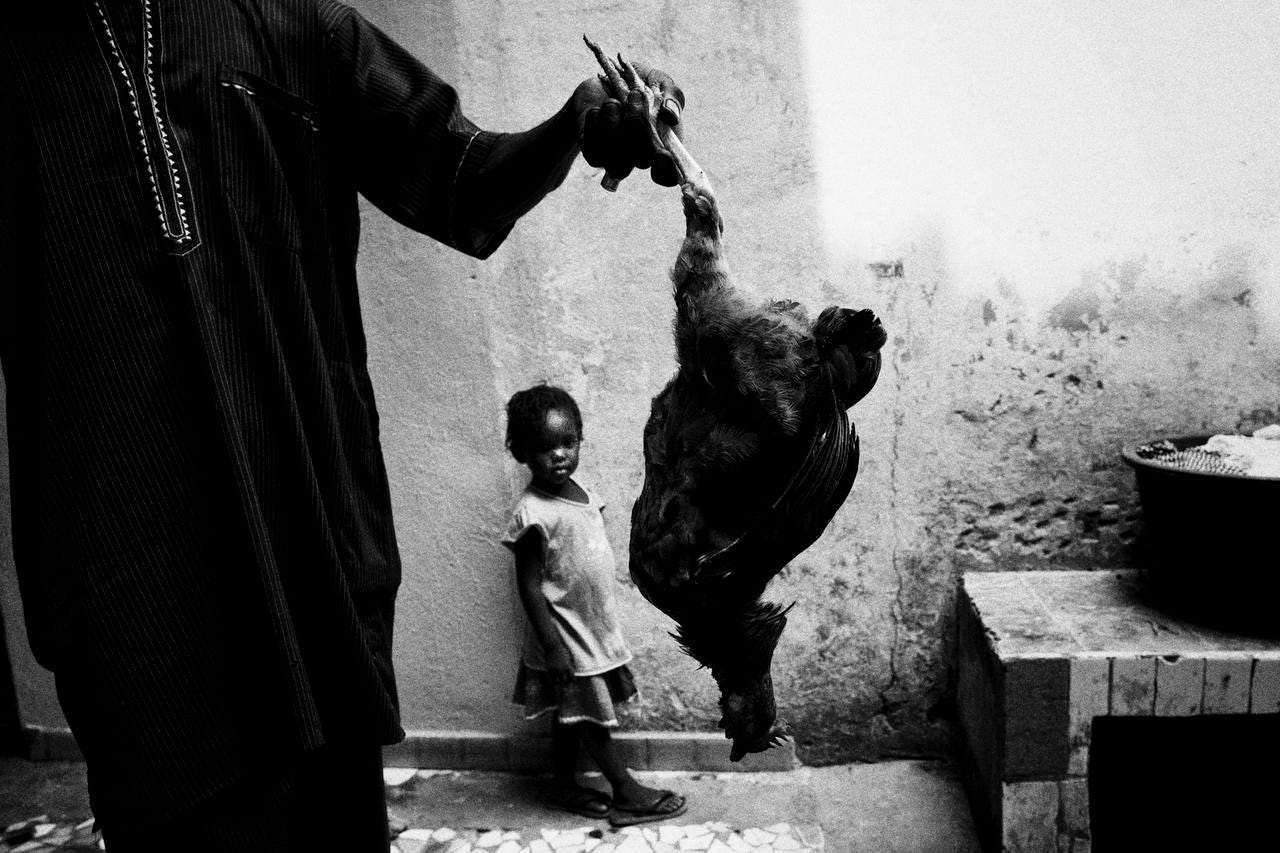

Voodoo Masters of the Dakar Darkness

Senegal may be overwhelmingly Muslim, but when serious spiritual help is needed, the country’s supposedly blasphemous Voodoo priests are happy to provide answers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.