What It Feels Like to Be Adopted at 17

After years of misery and abuse, I finally learned what it’s like to have a loving and supportive family—right before my childhood officially ended.

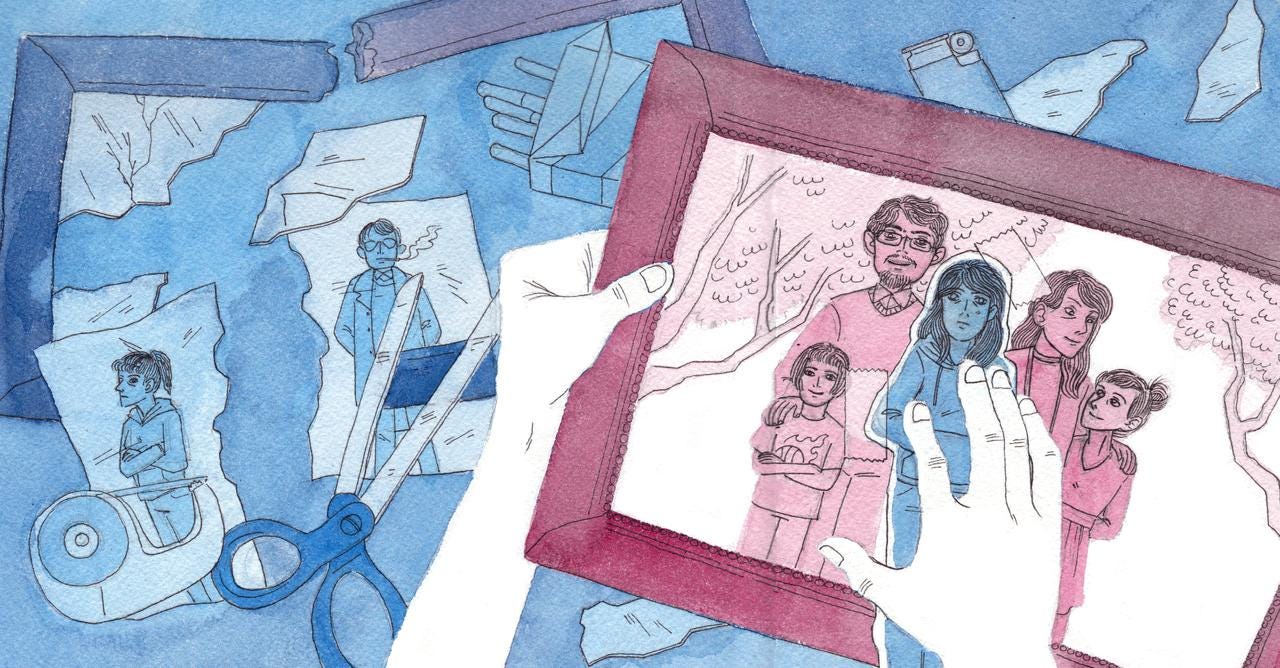

Illustration by Natalie Kassirer

Earlier this year, I legally became an Esparza, five years after they took me in. It took five years for me to realize that these people were serious about being my parents; five years of doubting their love, but yearning for what they claimed to offer.

We had to go to court and wear dresses and ties — it was kind of like a marriage. When I entered the building my body immediately tensed up, and my mom put her hand on the small of my back. We walked into the courtroom where the judge said she was grateful to be administering something positive for once.

The lawyer asked my parents if they understood that this bound them to me legally, something about provision for me, and they said “Yes” in unison, very straight-faced.

Then he turned to me and said my name, smiling, “Do you understand that from this day forward your legal name will be Lyric Alexis Gabriella Esparza?”

“Yes,” I heard myself say, anxiety now tearing through my chest. I felt both my parents’ ha…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.