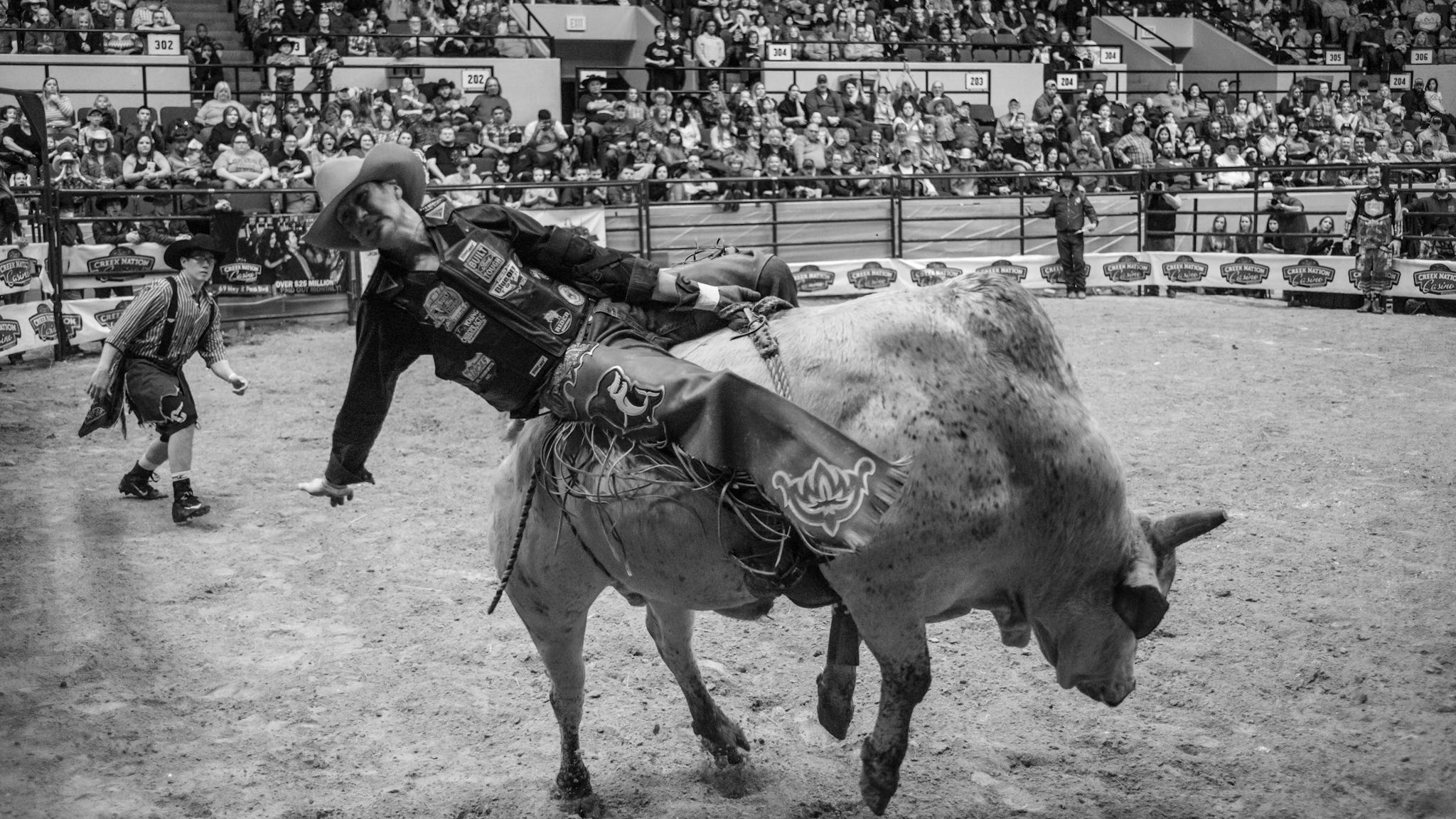

‘You’re So Pumped You Could Fight an Alligator’: The Promise and Pain of Pro Bull Riding

Once a rodeo sideshow, this perilous sport is now a $70-million business with cowboy superstars who take a lifetime’s worth of lickings and keep on kicking.

“The smarter you are, the tougher this is going to be,” David Berry, founder of the Monster Bull riding school in Locust Grove, Oklahoma, tells a class of aspiring young riders in his horse barn. Mostly teenagers, they are a mix of country and city kids who eagerly paid the $300 tuition for a weekend of instruction and a few rounds on Berry’s introductory-level bulls. Seated on hay bales, they watch slow-motion replays of rides from the Professional Bull Riders circuit (PBR). “See how he throws his arm back as the head comes down?” says Everett Bohon, Berry’s teaching assistant. He pauses the video and, using his iPhone, draws two parallel lines on the screen, delineating the bodies of bull and bull rider. “Look at his body here,” says Bohon. “Totally aligned with the bull’s – the key to a successful ride.” After another half hour of video instruction, the boys hop on a series of practice barrels to hone their posture and arm positioning, then head off t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Narratively to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.